A recent financial Webinar features Jindalee mining company executive Lindsay Dudfield selling the company’s plan for an immense lithium mining project that would tear apart the heart of irreplaceable Sage-grouse habitat at McDermitt Creek in southeast Oregon. Australian miner Jindalee has spun itself off as a US company, just as Lithium Americas did when it formed Lithium Nevada Corporation (LNC) to mine Thacker Pass further south in the McDermitt caldera. This positions the miners for federal loan largesse as they pursue mining destruction of the sagebrush sea. I wrote about the extraordinary McDermitt Creek values at stake, and the damage and habitat fragmentation already inflicted by 70 or so previous Jindalee exploration drilling sites here.

Distant view of scar from a new road and just one of Jindalee’s past McDermitt drill sites. Look at how wide open and unencumbered by hills this country is – maximizing the distance any mining disturbance sights and sounds will travel.

Jindalee drill hole sump. Drilling waste water left to seep into the ground, Wildlife “exclusion” fence fallen down.

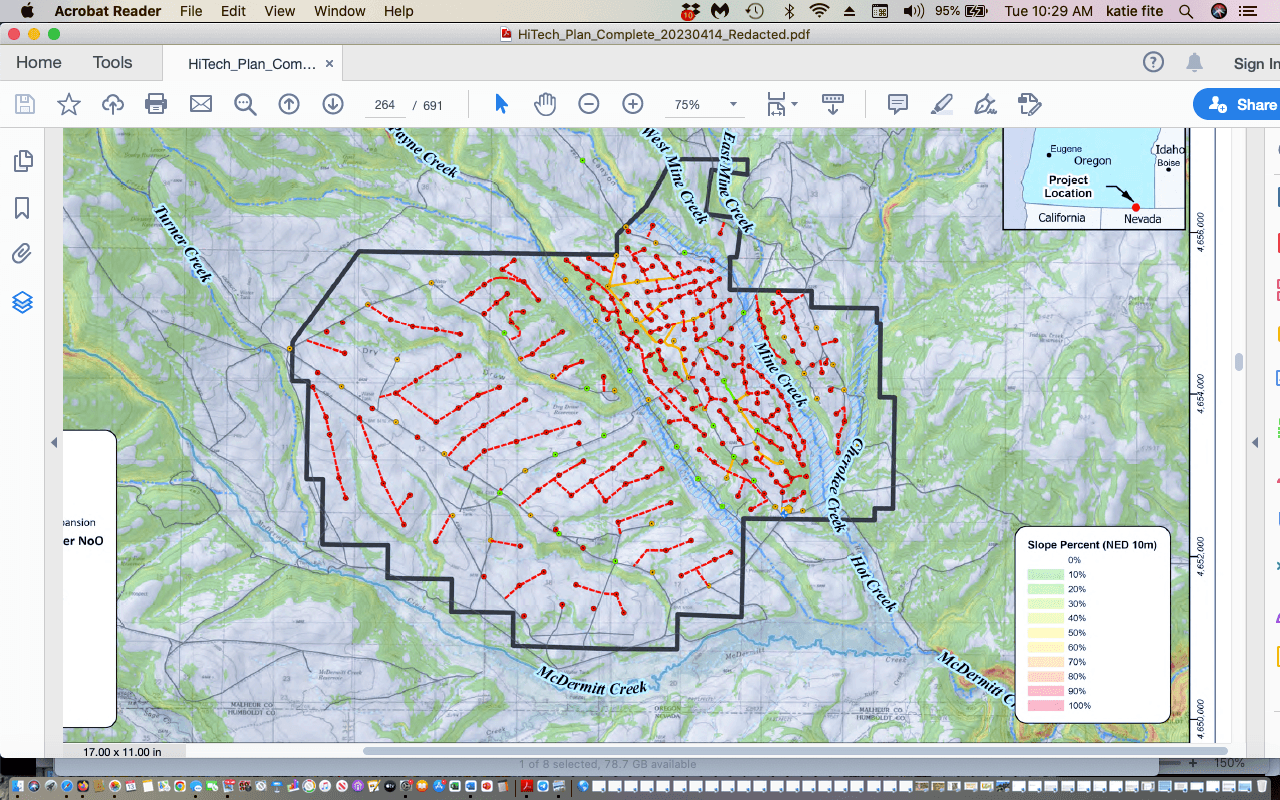

This is a map of the ghastly 2023 Jindalee exploration plan to punch in 267 new drill hole and sump sites and construct 30 miles of new roads. It would fragment an area with a very high density of nesting sagebrush songbirds of all kinds. Birds like Sagebrush Sparrow require continuous blocks of dense mature or old growth big sagebrush. Jindalee boasts its consultant environmental and cultural studies have found “no show-stoppers” and “no red flags”. Industry gets the results it wants when it pays for mine consultant work. Federal and state agencies, after a bit of pro forma sniping, acquiesce to what the mine comes up with.

This is a map of the ghastly 2023 Jindalee exploration plan to punch in 267 new drill hole and sump sites and construct 30 miles of new roads. It would fragment an area with a very high density of nesting sagebrush songbirds of all kinds. Birds like Sagebrush Sparrow require continuous blocks of dense mature or old growth big sagebrush. Jindalee boasts its consultant environmental and cultural studies have found “no show-stoppers” and “no red flags”. Industry gets the results it wants when it pays for mine consultant work. Federal and state agencies, after a bit of pro forma sniping, acquiesce to what the mine comes up with.

No red flags? Does the company really expect us to believe they or their consultants aren’t aware of the plight of Sage-grouse, and the importance of the stronghold habitat they would wipe out? The 2015 BLM Sage-grouse plan found the entire McDermitt Creek area and nearly all caldera lands were essential for the bird’s survival. BLM determined that a federal mineral withdrawal was necessary to protect this Focal habitat and to ensure Sage-grouse species survival. The withdrawal never happened, stopped first by mining and cattle industry litigation. BLM then began a stand-alone NEPA analysis for the withdrawal. Trump terminated that withdrawal analysis process. Then after a court ruled his action unlawful, BLM foot-dragging has stalled the most recent withdrawal process at the NEPA scoping stage and it appears merged with a cumbersome major plan revision.

Jindalee’s new exploration proposal – a prelude to a mine – would tragically rip apart the Basin heart. A full blown mine here would obliterate it. Mining noise and visual disturbance emanating outward would make the remaining sage ringing the mine site uninhabitable. The site is surrounded by dozens of leks.

The impossibility of mitigating a mega-mine at McDermitt Creek just blasted further into the stratosphere. Mounting scientific evidence shows how seriously the sight and sound disturbance footprint of industrial projects harms the birds. New research examined geothermal energy development impacts from Ormat plants at Tuscarora Nevada and McGinness Hills/Grass Valley near Austin. (I remember the Battle Mountain BLM manager extolling Ormat’s virtues when the McGinness project was pushed through and then later expanded to take a bigger bite out of sage habitat). New research found:

“… sage-grouse population numbers declined substantially in years following the development of a geothermal energy plant … sage-grouse abundance at leks [breeding sites] decreased within five kilometers of the infrastructure and leks were completely abandoned at significantly higher rates within about two kilometers. So, we looked at the mechanisms responsible for declines in numbers and lek abandonment, and we found adverse impacts to survival of female sage-grouse and their nests”.

This reinforces common sense: “Nests located farther from the plant tended to experience higher rates of survival. Interestingly, where hills were located between sage-grouse nests and infrastructure [high topographic impedance], we found the distance effect to be less important. Under those circumstances topography was compensating for the lack of distance and likely serving to reduce effects of light and sound”.

“The physical footprint of geothermal energy infrastructure is small relative to other renewable energy … but noise and light pollution emanating from these power plants likely cause larger adverse direct impacts to wildlife populations than infrastructure alone”.

There aren’t big hills to block a lithium mine’s 24 hour a day sight and sound impacts in the McDermitt bowl. The mined area would suffer outright sage obliteration. Surrounding sagebrush would be exposed to unimpeded straight line 24 hour a day mine operation visual impacts and noise of all kinds.

Jindalee must know of the indigenous opposition and resistance to the Thacker Pass lithium mine in the southern caldera, located in similarly unceded Paiute-Shoshone ancestral lands. Controversy and lawsuits over Thacker Pass have been in the headlines for years. It’s a pre-eminent example of an unjust transition to alternative energy and the green-washing of air and water polluting habitat wrecking dirty hard rock mining. Unfortunately, a District Court Judge’s ruling did not halt the Thacker Pass mine construction. However, the lawsuits by environmental groups, Tribes and a local rancher opposing the mine continue. The District Court decision was appealed to the Ninth Circuit, where a hearing is scheduled for June 26.

Thacker Pass mine development would destroy a Traditional Cultural Property, where Paiute-Shoshone ancestors were massacred. This spring, it’s been the site of the indigenous Ox Sam Women’s Camp, Newe Momokonee Nokotun, set up in protest. Descendants of Ox Sam, a survivor of a US cavalry massacre at Thacker Pass, helped establish it.

Jindalee Webinar statements also hint at efforts afoot to alter Oregon state mining processes. After lamenting the project wasn’t in Nevada, Jindalee said it was talking to politicians and the head of the state mining Department (DOGAMI).

The company’s braggadocio made me blow off deadlines and go once again to McDermitt Creek to document its great biodiversity values. I then went from the beauty of singing sagebrush songbirds, newly hatched Sage-grouse chicks and peaking rare plant blooms at McDermitt Creek (photos below) and down into the Montana Mountains by Thacker Pass.

Sagebrush Sparrows abound at McDermitt Creek. They’re great little birds and often sing throughout the day. And they’re vanishing from many places. A biologist just told me he thinks they may be extirpated in Morrow County Oregon where he’s long inventoried bird. No larger continuous blocks of lower elevation sage = no Sagebrush Sparrows.

Hymenoxys, an Oregon sensitive plant growing on clay soils.

Humboldt Mountains Milkweed, a medicinal plant, on clay soils.

Mountain Bluebird.

Sky drama all spring long.

Short-horned Lizard – a master of invisibility.

Gray Flycatcher. They nest in head high Basin big sagebrush, which is becoming as scarce as hen’s teeth.

Lark Sparrow. They’re exuberant singers and are dining on Mormon crickets at McDermitt Creek.

An indescribable Indian paintbrush hue.

We’re supposed to sit back and let all this beauty and biodiversity be destroyed for a lithium mine? No way.

Thacker Pass – Turmoil, Land Mutilation, Montana Mountains

I drove south to Orovada and headed west to the turn-off from the state highway into Pole Creek road, the main access to the Montana Mountains. Thacker Pass lies at the southern base of these mountains. A maroon Allied Security company truck squarely blocked the road. Chain link fencing with No Trespassing and No Drone Zone signs was placed off to both sides.

I stopped, got out and approached a security guard who appeared at the truck. He refused to let me pass. After several minutes of my insistent repetition that this was a public road, the BLM mine EIS said this road would always be open, and that blocking use of this road indicated the EIS, the BLM and Lithium Americas had lied, the security guard relented and said he would call the head of security.

I stopped, got out and approached a security guard who appeared at the truck. He refused to let me pass. After several minutes of my insistent repetition that this was a public road, the BLM mine EIS said this road would always be open, and that blocking use of this road indicated the EIS, the BLM and Lithium Americas had lied, the security guard relented and said he would call the head of security.

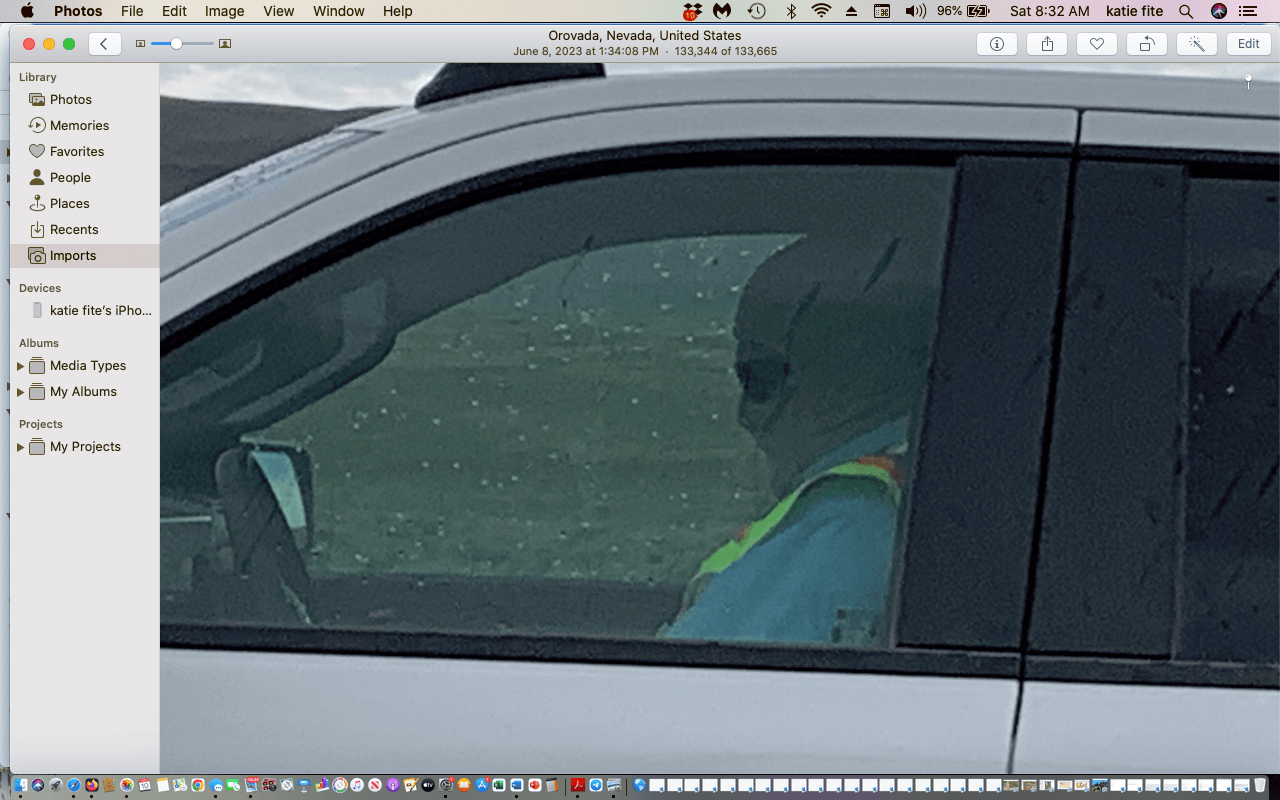

The boss pulled up in a white truck as a sudden rain whirlwind bore down. His face was obscured, and identity concealed by a tan balaclava-like hood and dark sunglasses. When he first arrived, he got out of his truck and pointed a camera device at me. I thought WTF is this – a security firm mercenary decked out for Operation Iraqi Freedom? Abu Ghraib in Orovada? I again repeated repeatedly that this was a public access road, and I was going up into the Montana Mountains to camp. He retreated to his pickup, likely to run me and my license plates through some creepy database. Finally, I was allowed to pass through.

The boss pulled up in a white truck as a sudden rain whirlwind bore down. His face was obscured, and identity concealed by a tan balaclava-like hood and dark sunglasses. When he first arrived, he got out of his truck and pointed a camera device at me. I thought WTF is this – a security firm mercenary decked out for Operation Iraqi Freedom? Abu Ghraib in Orovada? I again repeated repeatedly that this was a public access road, and I was going up into the Montana Mountains to camp. He retreated to his pickup, likely to run me and my license plates through some creepy database. Finally, I was allowed to pass through.

Just up the road was the Ox Sam Protest Camp site, located on a huge mine water pipeline gash that the lithium company had gouged into the earth. The pipeline gash runs right by the sacred Sentinel (or Nipple) Rock. The tents appeared lifeless, flaps blowing open in the rain squall as I drove by. With better cell phone service up in the mountains, I called Winnemucca BLM, asked to talk to a Manager, Assistant Manager, somebody, and told the receptionist that the mine was trying to block the public access road. She said there was no one to talk with. I asked for a Manager’s e-mall address. She refused to give me an address and shunted me to the general BLM mailbox where public comments go to be ignored. Winnemucca is the BLM outpost in charge of enforcing LNC’s compliance with EIS requirements. They’ll be sure to jump on enforcement actions when the public brings potential mining violations to their attention over the next 45-years.

Later I saw a Google alert for “Thacker Pass”, and read that the camp had been raided after an incident. Underscore News/Report for America writes: “On Wednesday, police from the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office and private security for Lithium Nevada, a subsidiary of Lithium Americas, cleared the camp and arrested one protester.

When I left the next day, the chain link fence with No Trespassing signs was still up by the sides of the access route. The security truck was gone, and I drove on through. A local resident pulled up. We chatted, gazing up at the mountains that were witnessing the lithium mine destruction unfold. He knows the country like the back of his hand. He said you could see over 20 mountain ranges from the Montanas. Our presence generated the interest of security guards who came by to check us out as we stood by the state road right of way. A project worker came and moved the chain link fence with its No Trespassing signs away – at least for now.

Allied Security’s aggressive approach to security has gained notoriety. The Denver city council canceled their contract after two Allied guards beat a black man so hard they caused him permanent brain damage. In May, Time magazine profiled a long troubling history of Allied incidents.

How fitting. Lithium Americas came in claiming Thacker Pass was some kind of great “green” mine, as cover for plain old dirty open pit mining and a noxious lithium processing plant. Now they’ve hired a security firm prone to violence. I don’t know what went down with the Ox Sam camp. But I do know that having the security boss decked out in black ops head gear is an effort to intimidate, and an indication the security firm may have things to hide. Security personnel concealing their identity or playing gatekeeper on a public lands access road in this way have no place at a project on public lands. Months before the Ox Sam camp was set up, LNC had established a manned compound with a building and fencing and what looked like cameras right by the Pole Creek access road. Driving up into the mountains in April to trek across the snow to the Montana-10 lek had already felt like running a gauntlet. I wager that anyone going in or out that public road gets recorded.

LNC has many mining claims staked up in the mountains in Sage-grouse stronghold habitat including at the Montana 10 lek. This makes efforts to limit access or intimidate people so they don’t go up there more concerning. Back home, I consulted the Thacker Final EIS:

“SR 293, Pole Creek Road, Crowley Creek Road and Rock Creek Road are the main transportation routes in the Project area. Under Alternative A, LNC would not close, block, or limit in any manner access along these routes”. FEIS at 494-495. The EIS also constrained use of these access roads for certain types of mine activities.

Photos below from up in the Montana Mountains looking down on spring 2023 LNC scars from drilling and bulldozing in migratory bird nesting season. The drilling is creeping upslope. It’s hard to tell if some may be outside the project boundary. Nevada BLM uses in-front-of-the-bulldozer bird survey protocols that are deeply flawed with transects spaced 100 ft. apart – a distance far too wide to detect cryptic sagebrush birds that are experts at concealment. You practically have to step on or by a nest to detect it. The only way to avoid migratory bird “take” is for the mine to not destroy the bird habitat in spring.

LNC’s drill scarring is a mere prelude to the destruction that’s planned – 5,694 acres of outright destruction in a 17,933 acre project zone. The enormity and scale of the planned mine is mind boggling – a deep open pit, a waste rock pile, all types of infrastructure, a lithium smelter/sulfuric acid plant on-site using huge volumes of waste sulfur shipped into a new railroad off-loading site by the Winnemucca airport. The latter was just announced a few months ago, to the dismay of nearby residents who find themselves facing living by a hazardous materials zone. Hundreds of tons of off-loaded material will be trucked to Thacker Pass and burned every day in a plant whose air scrubber design wasn’t even finalized before the Thacker decision was signed by BLM. What stink and toxic pollution will this lithium processing generate? McDermitt caldera soils contain uranium and mercury. Mine water use is estimated to be 1.7 billion gallons annually. Enormous volumes of diesel fuel will be used throughout the mine’s operation. What’s green about all this?

LNC’s drill scarring is a mere prelude to the destruction that’s planned – 5,694 acres of outright destruction in a 17,933 acre project zone. The enormity and scale of the planned mine is mind boggling – a deep open pit, a waste rock pile, all types of infrastructure, a lithium smelter/sulfuric acid plant on-site using huge volumes of waste sulfur shipped into a new railroad off-loading site by the Winnemucca airport. The latter was just announced a few months ago, to the dismay of nearby residents who find themselves facing living by a hazardous materials zone. Hundreds of tons of off-loaded material will be trucked to Thacker Pass and burned every day in a plant whose air scrubber design wasn’t even finalized before the Thacker decision was signed by BLM. What stink and toxic pollution will this lithium processing generate? McDermitt caldera soils contain uranium and mercury. Mine water use is estimated to be 1.7 billion gallons annually. Enormous volumes of diesel fuel will be used throughout the mine’s operation. What’s green about all this?

Think of the volume of water that will be sucked through these pipes.

Beautiful dense big sagebrush full of Sage Thrashers, Brewer’s Sparrows, and Sage-grouse sign, up in the mountains where LNC has claims galore.

Sacrificing the Interior West for Corporate Energy Dominance While Energy Conservation Lags or Is Forgotten Altogether

Sacrificing the Interior West for Corporate Energy Dominance While Energy Conservation Lags or Is Forgotten Altogether

Big Green environmental groups and outdoor interests who’ve been silent on the unfolding lithium mine destruction at Thacker Pass, or the tragic destruction of Mojave Desert Tortoise habitat for Big Solar and many other brewing “green” energy controversies better wake up. The lithium boom plague that’s descended on the West is hard rock mining at its worst. Thousands of acres at each mine site become essentially privatized (with security guards) for 40 or 50 years. Much of the land is reduced to waste rock rubble piles, gaping pits, infrastructure all over the place. Local water is used up for processing and for suppressing clouds of dust, and mine pollutants contaminate the air and ground water.

US taxpayers are helping finance these colonialist lithium mines. LNC received commitments for a $600 million dollar loan investment of US tax dollars. General Motors, while continuing to pump out gargantuan trucks and EV Hummers priced at $110,000, provided LNC with a $600 million dollar injection. In the Jindalee Webinar, executive Dudfield assured a questioner that their company will also be “in queue” for similar handouts. The miners are gobbling up funds for a battery technology that may soon be outdated. China is zooming past the US with its development of sodium batteries and is introducing them in low-end vehicles, a sane path forward. Why aren’t these funds going to research alternatives to lithium and safer less earth-wrecking technologies? Why isn’t Nevada Senator Catherine Cortez-Masto directing her attention to spurring new technologies and sustainability? Instead she’s using “critical minerals” mantra to justify introducing a bill to make the 1872 Mining Law even worse, and a wholesale giveaway to mining companies.

Jindalee’s Webinar talk said the company embraced “social license and responsibility”, then later emphasized that McDermitt Creek was “a long, long way” from Oregon population centers like Salem and Portland. This highlights how lithium mine pollution, cultural site desecration, community de-stabilization and ecological damage will be out of sight and out of mind of urban elites.

US government policy is now based on greatly accelerating energy colonialism of all types within our own borders, and especially on willy-nilly sacrifice of the public lands of the Interior West. This allows massively subsidized corporations (often tied to a foreign mothership) and billionaires to retain a chokehold on energy. Conservation is paid lip service. BLM’s Tracy Stone-Manning just announced a new proposed rule making it easier for BLM to hand over public lands to wind and solar developers, furthering de facto public lands privatization for half a human lifespan.

But people are catching on. A surprising thing recently happened in Idaho. The entire Idaho legislature (all the Republicans and the hand full of Democrats alike) voted in favor of a Resolution opposing the BLM Lava Ridge Wind Farm, with its 400 turbines standing 800 feet tall sprawling across 3 counties. Lava Ridge’s plan managed to offend or disgust everybody – from agricultural operations and home site impacts, to Golden Eagle and rare bat killing, to destroying the stark setting of the Minidoka Japanese Internment Camp Monument and marring the Dark Skies and wildness of Craters of the Moon.

If you live in the West and love the outdoors, be very afraid of what the Biden administration’s breakneck push for many more of these “green” lines will do to public lands, and your access to areas beyond – once projects feeding energy into the line are built and the fencing goes up. It’s the sagebrush sea equivalent of building a road through the Amazon.

While there are no huge wind farms yet on public lands in Idaho, there are many smaller scale turbine arrays on private lands across the Snake River Plain. It’s become quite apparent that industrial wind is not benign. Above all else, folks realized how badly Idaho was getting screwed by the Lava Ridge project and its export of energy to benefit coastal populations. The Legislature said No to Lava Ridge exploitation of Idaho as an energy colony. Counties in the Mojave Desert are now starting to resist some industrial solar developments overrunning public lands. Remotely sited “renewable” energy or “critical minerals” projects amount to public land privatization. They cause profound losses of many kinds – scarring the land, sucking it dry, extinguishing the wildlife that’s managed to persist in the face of merciless domination since White settlement, trenching a massacre site.

I’m outraged at the ecocidal stupidity with which this “energy transition” is being carried out. Will we soon see Jindalee get US tax dollars to wipe out the McDermitt Creek Sage-grouse stronghold? How ironic that would be. Interior just announced funding for major sagebrush habitat restoration using Infrastructure Bill funds in High Priority sagebrush areas. It turns out one of the sites chosen is the Montana Mountains area. Mapping shows it includes the Thacker Pass mine area too, where nearly all the sage is on the verge of being destroyed by LNC. Close review of maps for Interior’s Montana “restoration” project shows it encompasses the McDermitt Creek watershed, hence the entire area coveted by Jindalee for massive new drilling followed by open pit mining. It would be absurd to greenlight Jindalee’s ghastly exploration plan in primo habitat, when the Interior Department has identified this very same landscapeto be among the highest priority for restoration – because so much sage has already been lost already. The caldera is also key for connectivity between Sheldon and Owyhee Sage-grouse populations and for biodiversity preservation.

I’m outraged at the ecocidal stupidity with which this “energy transition” is being carried out. Will we soon see Jindalee get US tax dollars to wipe out the McDermitt Creek Sage-grouse stronghold? How ironic that would be. Interior just announced funding for major sagebrush habitat restoration using Infrastructure Bill funds in High Priority sagebrush areas. It turns out one of the sites chosen is the Montana Mountains area. Mapping shows it includes the Thacker Pass mine area too, where nearly all the sage is on the verge of being destroyed by LNC. Close review of maps for Interior’s Montana “restoration” project shows it encompasses the McDermitt Creek watershed, hence the entire area coveted by Jindalee for massive new drilling followed by open pit mining. It would be absurd to greenlight Jindalee’s ghastly exploration plan in primo habitat, when the Interior Department has identified this very same landscapeto be among the highest priority for restoration – because so much sage has already been lost already. The caldera is also key for connectivity between Sheldon and Owyhee Sage-grouse populations and for biodiversity preservation.

How long before rejection of lithium and other “critical mineral” mines grips communities, especially as promised jobs evaporate with increased mine automation and robot technology, and as the environment goes to hell? But hey, as LNC is showing us, there’s always a bright future as a security guard– at least until the lithium company gets itself a pack of Robodogs.