The Deep Green Resistance News Service is an educational wing of the DGR movement. We cover a wide range of contemporary issues from a biocentric perspective, with a focus on ecology, feminism, indigenous issues, strategy, and civilization. We publish news, opinion, interviews, analysis, art, poetry, first-hand stories, and multimedia.

DGR News Service

Texte intégral (3012 mots)

By Tom Murphy / Do the Math

Whenever I suggest that humans might be better off living in a mode much closer to our original ecological context as small-band immediate-return hunter-gatherers, some heads inevitably explode, inviting a torrent of pushback. I have learned from my own head-exploding experiences that the phenomenon traces to a condition of multiple immediate reactions stumbling over each other as they vie for expression at the same time. The neurological traffic jam leaves us speechless—or stammering—as our brain sorts out who goes first.

One of the most common reactions is that abandoning agriculture is tantamount to committing many billions of people to death, since the planet can’t support billions of hunter-gatherers—especially given the dire toll on ecological health already accumulated.

Such a reaction definitely contains elements of truth, but also a few unexamined assumptions. The outcome need not be reprehensible for several reasons.

We All Die

Presumably this doesn’t come as a shock to anyone, but the 8 billion humans now on the planet are all going to die: every last one of them. This will happen no matter what. It’s inevitable. No one lives forever, or even much beyond a century.

Are we mortified by this news, intellectually? Of course not: our individual mortality comes as no great surprise. Some even accept it emotionally! So, there we go: whatever (realistic) proposal anyone else might offer for how humanity goes forward has the exact same consequence: OMG: you’ve just committed 8 billion people to die! You decide to have toast for breakfast? 8 billion people will end up dying. Nice going. Monster.

Timescales

I suspect that many strongly-negative reactions to suggestions that we adopt a “primitive” (ecologically-rooted) lifestyle trace to an implicit assumption about timescales. Maybe this is a result of our culture’s short-term focus on quarterly profits, short election cycles, or any other political proposal that tends to promise short- or intermediate-term results. So, perhaps it is assumed without question or curiosity that I am talking about a radical transition taking place over years or decades rather than centuries or even millennia. I would never…

Maybe I need to be better about pre-loading my discussion with this temporal context, since the assumption of short-term focus is so universal, and I get accused of misanthropy for something I never said—a running theme in this post. Abandoning agriculture need not happen overnight (and can’t, reasonably)!

Hypocrite!

Some of the angrier reactions suggest I volunteer to be one of those killed dead as part of my assumed/conjured “program,” or that I get my hypocritical @$$ out into the woods to eat lichen, naked. First of all, normal attrition, accompanied by sub-replacement fertility, is all it takes to whittle human population down, without requiring even a single premature death. And suppressed fertility needn’t be programmatically mandated like it was in China for a few decades: it’s happening on its own volition right now, around the globe. Roughly 70% of humans on the planet live in countries whose fertility rate is below replacement. It’s not a niche phenomenon, and presages a nearly-inevitable population downturn once the already-rolling train reaches the reproductive station in a generation’s time.

Part of the “you first” reaction, I believe, relates to our culture’s emphasis on the individual self. People automatically translate that I am asking them, personally, to become a hunter-gatherer or die. Again, I never said that, but it’s not unusual for people conditioned by our culture to take things personally, given ample reinforcement that we are each the deserving center of our own universe and little else matters. It is therefore understandable that members of modernity would assume (project) the same outlook is true for me. For those operating under this narrow (self-referential) assumption of how all others work, many valuable voices in the world must become baffling—or suspected of being disingenuous—which is a little sad.

When I point my passion toward avoiding a sixth mass extinction (which I interpret to include humans), I am not thinking about myself at all, but humans not yet born and species I don’t even know exist. My concern is focused on the health and happiness of a biodiverse, ecologically rich future. I myself am practically a lost cause as a product of modernity still trapped within its prison bars, and sure to die well before any of this resolves. Moreover, I can’t decide to roam the local lands hunting and gathering as long as property rights prevail and I do not enjoy membership in an ecological community operating outside the law. But, what I cando is try to get more people to wish for freedom, so that when opportunities arise good things can germinate in the cracks and force the cracks wider—even if I’m long gone when the crumbling process is complete. To repeat: it’s not about me. Talk of hypocrisy misses the boat entirely, by decades or centuries.

Not Even a Choice

Even if my audience gets over the shocked misimpression that I’m not talking about them personally, or a transition in their lifetimes, the objection can still remain strong. Isn’t keeping something like 8 billion humans alive indefinitely (via replacement in a steady demographic) far superior to something like 10–100 million hunter-gatherers living in misery?

First, the Hobbesian fallacy of believing foraging life to be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short” is so far off the mark and ignorantly uninformed as to be pitiable—but certainly understandable given our culture’s persistent programming on this point. Christopher Ryan’s Civilized to Death does a fantastic job dismantling this myth based on overwhelming anthropological evidence. Turns out we don’t get to fabricate stories of the past out of whole cloth (i.e., out of our meat-brains), without one bit of relevant knowledge or experience.

More broadly, if one’s worldview is that of a human supremacist (nearly universal in our culture, after all), then preservation of a ∼1010 human population makes complete sense: can’t have too much of a godly thing.

But we mustn’t forget that 8 billion humans are driving a sixth mass extinction, which leaves no room for even 10 humans if fully realized, let alone 1010. Deforestation, animal/plant population declines, and extinction rates are through the roof, along with a host of other existential perils. We have zero reason or evidence to believe (magically) that somehow 8 billion people could preserve modern living standards—reliant as they are on a steady flow of non-renewable extraction—while somehow not only arresting, but reversing the ominous ecological trends.

No serious, credible proposals to accomplish any such outcome are on the table: the play is to remain actively ignorant of the threat, facilitated by a narrow focus on this fleeting moment in time during which the modernity stunt has been performed. If ignorance did not prevail, we’d see retreat-oriented proposals coming out of our ears for how to mitigate/prevent the sixth mass extinction—but people say “the sixth what?” and go back to focusing on the Amazon that isn’t a dying rain forest. Most people know about climate change, but the dozens of “solutions” proposed to mitigate climate change amount to maintaining full power for modernity so that we motor-on at present course and speed under a different energy source. The IPCC never recommends orders-of-magnitude fewer humans or abandoning high-energy, high-resource-use lifestyles…because it would be political suicide—which says a lot about the limited value of such heavily-constrained institutions.

Saying that the planet (and humans as a part of it) would be better off with far fewer people can result in my being labeled a misanthrope, though I’ve never said I dislike people. I’ve heard it put nicely this way by several folks: I don’t hate people. I love them—just not all at the same time.

Quantitatively, 10–100 million humans on the planet for the next million years seems far preferable to 10 billion for only 100 or so more before the dominoes fall in a cascading ecological collapse at mass-extinction levels. Factoring in infant mortality and life expectancy among pre-historic people, a population of 10–100 million for a million years translates to roughly 200 billion to 2 trillion adults over time—far outweighing the total human life of 10 billion over a century or two.

Perhaps, then, I’m justified in turning the tables: reacting in horror to those who would propose to maintain a population of 8 billion, as this effectively condemns humans to a short tenure before mass extinction wipes us out. Why do proponents of maintaining present population levels hate humans so much? I’m actually serious!

Try this on: people love their kids, right? Let’s say that parents having 1–10 children are capable of expressing adequate love and providing adequate resources for all their kids. But if kids are so great, why not have 800 per family? You see, even great things cease to be great when the numbers are insane. 10–100 million humans can know a love and provision from Mother Earth that 8 billion surely will not. It’s madness, and our nurturing mother is being ravaged by the onslaught of the teeming, unloved—thus unloving—masses. Indeed, our culture wages war against the Community of Life, erroneously convinced that it was at war with us first. Yet, it created us, and nurtured us, or we would not be here!

Allowing normal demographic reduction to a sustainable population maximizes the total number of humans able to enjoy living on Earth. Now, I can’t really justify that as a valid metric—especially given our crimes against species—but I’m exposing my bias as a human (short of human supremacy: just expressing a preference that humans have some place on Earth rather than none). Not all human cultures have acted as destructively as ours, by a long shot, and many have considered Earth to be a generous, nurturing partner. Sustainable precedents liberally spread across a few million years at least somewhat justify the belief that humans canenjoy living on Earth without killing the host, and I’ll take what I can get.

Space Parallel

Tipped off by Rob Dietz of the Post Carbon Institute, I listened to a fantastic podcast episodecalled “The Green Cosmos: Gerard O’Neill’s Space Utopia”. In the last four minutes, professor of religion Mary-Jane Rubenstein reported that her students held an inverted sense of the impossible. To them, it was utterly impossible to imagine living on Earth with “nothing” (tech gadgets) as our ancestors actually really definitely did for millions of years, while not doubting the possibility that we could build space colonies in the asteroid belt and keep our devices and conveniences—despite nothing remotely of the sort ever being demonstrated. The delusion is fascinating, reminding me of Flat-Earthers, as featured in the insightful documentary “Behind the Curve.” Just as the earth looks flat to us on casual inspection, a few expensive stunts make it look to the faithful like we could someday colonize space. That’s right: I’m lumping space enthusiasts in with Flat-Earthers: enjoy each other’s company, folks!

But the base disconnect is very similar, here. Maintaining 8 billion human people on Earth is no more possible than invading space. It’s not an actual, realizable choice—beyond transitory and costly stunt demonstrations.

Hating the Likes?

The other head-exploding facet to the proposal of a much-reduced population living in something closer to our ecological context is that it would seem to amount to a callous repudiation of precious products of modernity: opera, symphony, great art, lunar landings, modern medicine, David Beckham’s right foot… Why do I hate these things? Well, I never said I did. Again with the words in my mouth… What I—or any of us—might like or dislike is completely irrelevant when it comes to biophysical reality and constraint.

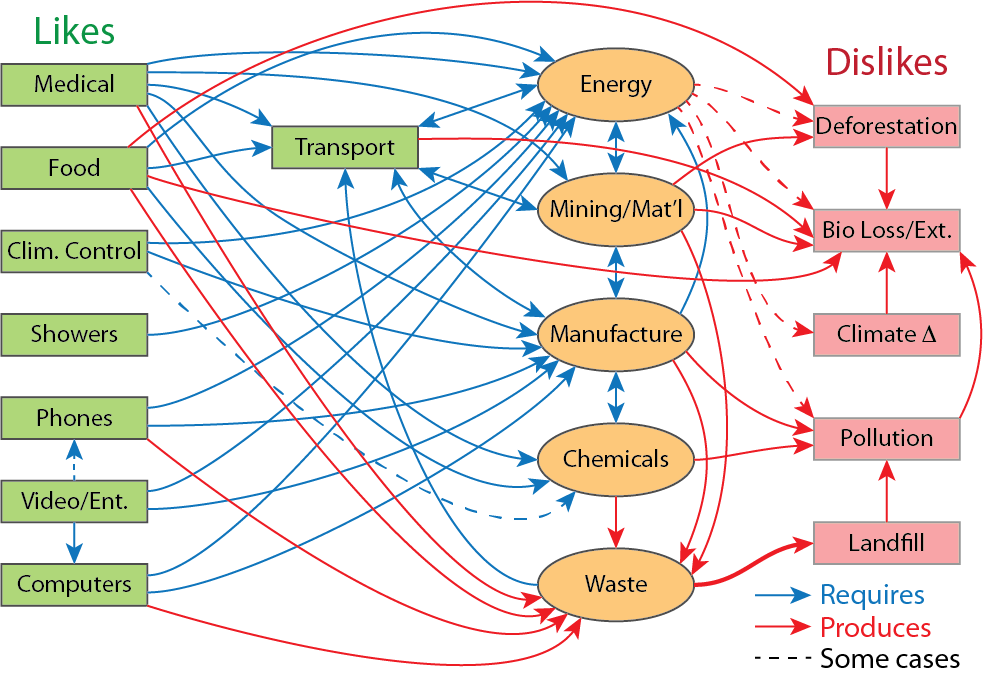

What makes us think we have a choice to separate the good from the bad, when they are most decidedly a package deal that we’ve been wholly unable to separate in practice, all this time? The following tangled figure—itself a staggering oversimplification of the actual mess—is repeated from an earlier post on Likes and Dislikes.

The fundamental flaw is that when faced with an unfamiliar landscape, our brains instantly and automatically assign separate qualities and features to a reality that in truth is inseparably inter-linked. Because the connections are numerous and often far from obvious, we are tricked into believing the entry-level mental model of separability. It’s the most basic and naïve (often adaptively useful) starting point to recognize a bunch of “things” without delving into the Gordian Knot of relationships. But that’s the easy part, and many stop there before it gets hard—often too hard for the very limited human brain, in fact. No blame, here: we all do it.

The Likes and Dislikes are a single phenomenon, having multiple interrelated aspects. Despite initial unexamined impressions, apparently we don’t actually get to choose to have modern medicine without advancing a sixth mass extinction. I’d give up a lot to prevent such a dire outcome—including modern medicine, since preserving it appears to translate to its own terminal diagnosis. Living seven decades is not rare in hunter-gatherer cultures; dental health is far better without agricultural products like grains and sugars dominating diets; and the chronic diseases we know too well in modernity are effectively absent for foraging folk (and notbecause lives are too short to expose them to the possibility—look deeper!). Modern medicine has extended adult life expectancy (once surviving infant mortality) maybe a decade or two, but at orders-of-magnitude greater per-capita ecological impact: a fatal “bargain” that calls to question our judgment.

Let the Standing Wave Stand

Some cloud patterns stay fixed relative to terrain—a coastline or mountain range/peak—even though the wind whisks along (see orographic and lenticular cloud formations). Moist air condenses at the leading edge, droplets careen through the formation, then evaporate on the trailing edge. These “standing wave” patterns are at once stationary and dynamic, with individual constituents playing a transitory role in a larger, more persistent phenomenon.

Human lives are similar: we flow into and out of life, while genetic patterns preserve a slowly-evolving human form across generations. The problem is that the magnitude and practices of the phenomenon are destroying the ecological conditions that allowed the phenomenon to arise and get so large in the first place. Our 8-billion-strong “cloud” is grossly unsustainable, so that it will collapse via its own downpour if not allowed to shrink. It’s possible to do so by natural attrition and generational transformation of lifestyles. While many factors threaten to make such a transition turbulent and “lossy,” the endpoint itself does not inherently demand a tortured path. Again, given modernity’s structural unsustainability, where we end up is not reallyan open choice. So, it’s best do what we can to make the only real positive outcome emerge as smoothly as it might: by embracing it and leaning into it rather than putting up a futile and destructive resistance that will hurt (all) lives far more than on the gentler path. Either way, 8 billion people will die. The bigger question is: will millions still live?

By Michael Dornbierer from Wikimedia Commons

DGR News Service

Texte intégral (1849 mots)

Editor’s: Trapped in a Tank: The Hidden Cruelty of the Tropical Fish Trade

The Exotic Pet Trade Harms Animals and Humans. The European Union Is Studying a Potential Solution

By Spoorthy Raman / Mongabay

Although a superpower, the U.S. is under constant invasion — we’re not talking humans here but meek-looking plants and animals that have caused ecological havoc. Take, for instance, the tiny, nocturnal coqui frogs (Eleutherodactylus coqui) in Hawai‘i that arrived from Puerto Rico in the 1980s and are now terrorizing the islanders with their deafening “ko-kee” calls that can be as loud as a motorcycle engine. With numbers in Hawai‘i now surpassing those in Puerto Rico, the frogs have scrubbed the forest floor and treetops of vital pollinating insects, toppled property prices in prime real estate markets, and are hurting tourism.

It’s not just the frogs: Burmese pythons (Python bivittatus), Argentine black-and-white tegus (Salvator merianae), European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris), invasive carps in the Mississippi, zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha), English ivy (Hedera helix) — the list is long. Many of these were legally imported, either as ornamental plants, bait or exotic pets, but soon escaped into the wild and established themselves, devastating the local environment and costing the U.S. economy more than $1 trillion.

“Prevention is the most effective and cost-efficient way of preventing those impacts that we know that nonnative species can have,” said Wesley Daniel from the U.S. Geological Survey.

A starting point is figuring out which of the thousands of species imported into the country are most likely to become invasive. So that’s what Daniel and his colleagues did. The findings from their recently published study identified 32 legally traded nonnative vertebrate species in the U.S. that have the highest risk of becoming invasive species, harming not just the environment but also human health.

“We’ve identified a subset of species that we think are potentially problematic if they’re released into the wild, and that gives us an opportunity to think critically about legal importation of those species,” Daniel told Mongabay. “The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is taking our list and considering those species for further review.”

The researchers sifted through an initial list of nearly 10,000 species by looking at data from the Law Enforcement Management Information System (LEMIS), a database maintained by USFWS that records all wildlife imported into the U.S. and those in the pet trade. They narrowed their list down to 840 species based on how similar the climate is in their native range to that of the U.S. and its territories.

Then, multiple experts, based on what they knew about the species, scored each species on how well it can establish itself, how well it can spread, and its potential impacts. In the end, 32 species — 22 reptiles and nine fish — stood out as “high risk” in the ranked list of vertebrates that can become invasives. All these species are currently legal to trade in the U.S.

The reptiles include venomous snakes such as the puff adder (Bitis arietans), zebra spitting cobra (Naja nigricincta) and forest cobra (N. melanoleuca) — all native to Africa — responsible for snakebite deaths and injuries in their native range. Others include four species of tree-dwelling snakes and three constricting snakes, which share similar ecological traits with known invasives such as the brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis) and Burmese python, respectively. Predatory monitor lizards (Varanus spp.) also featured on the list.

“We don’t need more monitor lizards; there’s plenty down here that already escaped captivity,” Daniel said, referring to the spread of the Argentine black-and-white tegus in Florida. These lizards, originally sold as pets, escaped captivity and became established in Florida’s Everglades in the 2000s, causing widespread damage, including eating alligator eggs, threatened gopher tortoises and even agricultural crops. The state has since spent millions to remove them, and the lizards are now considered a prohibited species to own in Florida and Georgia.

The nine fish species identified as high risk for becoming invasive are those that are either traded as pets or in aquaculture. Many are already considered invasive species elsewhere, such as the common bream (Abramis brama), from Europe, and ornamental fish like the blood-red jewel cichlid (Hemichromis lifalili), native to the Congo Basin.

Although no birds, mammals or amphibians were considered high risk, the study identified 54 bird, 11 mammal and one amphibian species as medium risk.

“Wildlife trade is a massive and underestimated threat to many species, but also poses a threat to species in the country it is imported to,” wildlife trade researcher Alice Hughes from the University of Hong Kong, who wasn’t involved in the study, told Mongabay by email. She added that in addition to the species themselves being a threat, they can bring in pests and pathogens that affect native species.

“This study explores the magnitude of the potential threat [and] reinforces what we know about the risks of importing wildlife,” Hughes said.

The list of high-risk species provides a starting point for agencies such as USFWS to dive deeper into the specific risks they pose, and restrict or regulate their import by adding them to injurious wildlife listings. Daniel said USFWS is already using the list the study’s authors prepared to assess each of the high-, medium- and low-risk species individually. The state of Arkansas is also studying the list of high-risk fish to develop new regulations.

“We hope other tribes and territories and states can also get on and look within their jurisdiction where there could be risky species, and start making some of those own decisions about policy,” Daniel said.

Spoorthy is a Mongabay staff writer based in St. John’s, Newfoundland, who covers wildlife issues and an array of other topics. Previously as an independent journalist covering science, environment, and more, she reported feature stories, personal essays, and news articles for outlets ranging from Hakai to Audubon, BioScience, Scientific American, Nature, Science, Deccan Herald, The Open Notebook, The Print and others.

Banner image: Puff Adder, a venomous snake from Africa, topped the list of vertebrates with the highest risk of being invasive in the U.S. Image by Christiaan Viljoen via iNaturalist (CC BY 4.0).

DGR News Service

Texte intégral (4351 mots)

Editor’s note: “Protest alone, disconnected from more substantive action, is akin to screaming in the wind. Protest is not resistance. Protest, whether conscious to it or not, often reinforces the belief that the system is fundamentally sound, and that with reform it can resolve the issue that sparked the protest. We must confront the truth: our system of governance is fundamentally flawed. It is corrupt, hierarchical, unfair, and thoroughly infiltrated by corporate power and special interests.”

What do we do when protests and elections fail?

People deserve to be included in the processes of making political decisions about the places where they live. People deserve equal access to economic resources and opportunities. People deserve to have a say in environmental decisions that affect the health and well-being of their communities. People deserve to be able to govern their places in a way that maintains healthy, long-term relationships among humans, other living things, and the physical environment.

It is the final week of February 2024, and the City of London, the capital’s ancient financial district, where corporations cluster like woodland trees, is teeming with climate activists. For three days they march the streets, block the entrances, and infiltrate the lobbies of major insurance companies. They act as part of a global campaign by an alliance of groups, and their aim is simple: stop the insurers from underwriting new fossil fuel infrastructure. This protest will end up showcasing both the pruning of one type of climate activism, and the blossoming of another.

The first activists to be arrested are a five-strong Extinction Rebellion troupe dressed like 1940s washerwomen, complete with hair curlers, heavy makeup and rubber gloves. Known as the Dirty Scrubbers, their plan is to performatively clean some corporate entrances, and dye some fake money green in their ‘greenwashing machine’ – an old washing machine on bike wheels. The action encapsulates much of what made Extinction Rebellion a global phenomenon – fun, theatrical, eye-catching activism that still has a bit of bite. The police commander is informed by protest organisers and gives the performance the go ahead. But half an hour later, the police on the street have other ideas. Thirty officers surround the Dirty Scrubbers as they wheel their greenwashing machine into the protest zone, and arrest them for conspiring to cause criminal damage. Only some are handcuffed, but all are loaded into vans and held in police cells until the evening. Their greenwashing machine is impounded.

On the third and final day of the protest, in the early hours of the night, a previously unknown group makes its debut. Hooded activists wielding paint-filled fire extinguishers spray the entrances of three insurers and flee the scene before the police arrive. Rather than getting cleaned by the Dirty Scrubbers, the skyscrapers end up stained blood-red by anonymous members of Shut The System (STS).

The Dirty Scrubbers are led into police vans, City of London, February 27, 2024. Photo: Extinction Rebellion UK

In their online manifesto (now taken down), Shut The System promise to “shut down key actors in the fossil fuel economy” by waging an escalating “campaign of sabotage.” True to their word, their sabotage escalates. When they return to the streets four months later, this time to target Barclays bank in a joint action with Palestine Action, they don’t just spray-paint the bank’s glass fronted buildings, they smash them too. More than 20 branches are temporarily shut down across the UK to pressure the bank to divest from fossil fuels and Elbit Systems, Israel’s biggest weapons manufacturer. Weeks later, they return to the City of London to deface and smash insurance company windows.

Then in January of this year, Shut The System try a new, more sophisticated kind of sabotage – cutting fibre optics cables. First to be forced offline is a collection of climate-denying lobby groups housed a stone’s throw from the British Parliament. Two weeks later, Shut The System target those major insurers again, this time severing cables of firms not just in the City of London but also in Leeds, Birmingham and Sheffield.

Most recently, they target the private homes of three Barclays executives. On the morning of the bank’s AGM, its CEO, global head of sustainable finance, and president find their luxury properties spray-painted with messages demanding an end to fossil fuel investments. Cables are also cut at Barclaycard’s UK headquarters, and more than 20 bank branches have their door locks and ATMs superglued shut.

The ‘campaign of sabotage’ quickly bears fruit. A week after its entrance is stained blood-red, the insurance company Probitas declares it will not insure two ‘carbon bomb’ projects singled out by protesters (the East African Crude Oil Pipeline and a proposed coal mine in North West England). Days after Shut The System and Palestine Action shatter Barclays bank branches, its CEO writes an op-ed in the Guardian renouncing the damage and voicing concern about the “overall suffering” in the Middle East. Four months later, the bank has sold all of its shares in Elbit Systems.

A long-term member of Shut The System, who required total anonymity to be interviewed, was happy to outline the strategy behind their ‘campaign of sabotage’: “We want to give the climate movement more teeth by training up people and getting them into these sorts of actions, mobilising further across Europe and the world,” they say. “So when fossil fuel companies are presented with demands by protesters, they can expect the tactics we provide. There’s power in that. These industries will know that we’re escalating, know that we care about this, and know that we’re not going away.”

In adopting and spreading sabotage, Shut The System doesn’t see itself as breaking away from the climate movement’s sustained adherence to non-violence. My contact instantly references the author of the manifesto How to Blow Up a Pipeline to explain: “I’m in complete agreement with Andreas Malm. Violence can be done to people, but not to buildings or infrastructure. We will not harm individuals.” Asked if they’d be willing to cut the cables of the home of, say, an oil company CEO, they don’t hesitate; “personally speaking, that’s within my limits. These people are killing people.”

But the use of sabotage does mark STS apart from the climate movement in other ways. The tactic necessitates a radically different culture to earlier organisations like Extinction Rebellion (XR) and Just Stop Oil (JSO), one where the need for security, and the fear of infiltration, reshapes nearly everything else. Reaching a member of STS for interview required multiple approaches. Once contact was made, Signal had to be jettisoned for a more anonymous messaging app. The days of open meetings in community halls and welcoming spokespeople is long gone. It begs the question, if you want to be a part of STS, how do you join? “We grow through people who know people, reaching out through a chain of trust,” says my contact. To become a member, you must be vouched for by at least two current members of STS, and members with deep roots in the climate movement are encouraged to scour their contacts for candidates. “We often find that people we’ve reached out to have been seeking a route in for a long time.”

This chain of trust spreads right across the UK, but it is a patchwork quilt, not a uniform fabric. Nobody can know everybody in STS, and group meetings are deliberately avoided. “Someone could have their phone taken away by police or put on remand. One person’s security failure could take out a lot of people” says my contact. Instead, a central team of organisers will chat with local leaders to agree on targets and dates and times, as well as pass on tactical knowhow. When it comes to deciding the specifics of an action – who takes which target, who adopts what tactic – the group operate like a take-away restaurant. “A long menu of possible options is sent around, and local cells then decide what they want to do based on location recces and capacity.”

A Barclays bank branch in Bristol after a joint nationwide action by STS and Palestine Action, June 10, 2024. Photo: Martin Booth

Shut The System is a year old, and the menu system appears to be working. But it does raise issues around power distribution and decision-making. A typical STS activist will not know who writes the menu, nor have a say over what dishes are made available. Their experience of STS will rarely if ever breach the limits of their local cell. It’s a long way from the open strategy meetings of XR, or the large social soup nights of JSO, where power is mitigated and community fostered as much as possible. My contact accepts the criticism: “There are no elections right now for the central team, but questions are being asked about this. And we do want a system of feedback, but security is just so important.”

Questions are also being asked in the central team about money. Namely, how can supporters chip in so STS members can focus on action research and development full-time. “Applying for funding through the normal climate movement routes is very difficult,” confirms my source. “So far we’ve raised small amounts, mostly on the backs of individuals. We have plans afoot for many more types of sabotage, but the scope to try different things is dependent on finding funding.” Asked for possible solutions, my source can only say, “we’re working on it.”

The artistic side of the climate movement, so intrinsic to XR and offshoots like the Dirty Scrubbers, has also been sacrificed on the altar of security. The central team have little interest in branding, messaging, or media. “We do have a logo on Instagram,” points out my contact. “But our visual and social media content is minimal – a recognition that being in any kind of contact with our group holds risk. It’s not a philosophy, just a result of priorities. Our circle’s central concern is security.”

If STS is the vanguard of a new phase in the UK’s climate movement, this phase isn’t as accessible, transparent or fun as what came before. But my contact is sure that this self-described “darker, more serious wing” is needed. With a climate denier in the White House, Big Oil ripping up pledges to decarbonise, the planet heating faster than predicted, and climate scientists warning that cataclysmic tipping points could happen as soon as this year, it’s not surprising that some ecoactivists are ready to embrace more militant tactics. But when I ask my contact what drew them to sabotage, the worsening status quo, and the apparent failure of traditional protest tactics to reverse it, weren’t the only factors.

My contact first got involved in ecoactivism after the Covid pandemic, when a friend invited them to a local XR meeting. Impressed by the confident activists they found there, they started taking part in actions. As they spent more time in the movement, they learned about the global struggle for environmental justice, including brutal events like the Ogoni 9, where nine Nigerian activists opposing Shell’s drilling of the Niger delta were framed for murder and hanged in 1995. The UK-based oil giant was implicated in both their false charges and a long campaign of violence in the region. These corporate crimes fundamentally shifted how my contact saw XR’s activism: “What we were doing was engaging the public, but it started to feel too performative, like an illusion. We had this messaging of crisis, of lives being at risk, of needing to change right now! But we weren’t willing to really threaten the institutions most responsible.”

I put the criticism to Richard Ecclestone, an XR spokesperson and former police inspector. He is sympathetic: “I understand why they expressed those views. I’m horrified by the behaviour of companies like Shell, Barclays, Perenco (an Anglo-French oil company accused of ongoing ecocide in the DRC).” Ecclestone is also sympathetic towards their use of sabotage: “Personally, I don’t believe action against property is violent when you consider the harm being done by these companies to people and planet. A tiny amount of damage to their operations could be justified. That’s my take. Others within the movement will think different. We’re a broad church.”

But this doesn’t mean Ecclestone will be joining Shut The System anytime soon, nor that he would welcome their tactics in future XR campaigns. “Our actions need to stick to our principles and values, and one of those is that we are accountable,” he says, meaning XR activists must accept the repercussions of their actions, including arrest. “If there’s no firewall between accountable and nonaccountable actions, we expose our people to extra risk, and that will hurt marginalised groups who for one reason or another can’t take on that risk. We have to do our best to be a home for everyone in the UK who wants to express their right to protest.”

City of London insurance firms are again visited by STS overnight, July 24, 2024. Photo: Shut The System

Another factor that steered my STS contact towards unaccountable sabotage was the increasingly draconian punishments the British state was dishing out to peaceful protesters. “Just Stop Oil’s campaign of blocking roads and disrupting sports events really boosted the signal – put the words just-stop-oil in every mind in the country,” they enthuse. “But the prosecutions and prison sentences have been ridiculous. If I’m going to go down and do time, I want to cause the maximum amount of disruption in the time I have, and that means covert actions.”

Since the rise of groups like XR and JSO, the UK government has been introducing increasingly repressive anti-protest laws, at least some of which were drafted by an oil-funded lobby group targeted by STS cable-cutters. The latest legislation started being enforced by police last year. As a result, unprecedented numbers of nonviolent protesters, mostly members of JSO, have been either imprisoned for years or paralysed by bail conditions for years as they wait for the overwhelmed justice system to put them on trial. The new laws have been used for even mildly disruptive actions like slow-marching, and when activists do have their week in court, the new legislation allows judges to strip them of all legal defences and ban them from mentioning climate change to juries.

After nearly 200 prison sentences, thousands of court cases, and the government adopting their core demand to stop new oil and gas, JSO has ended its three-year campaign. Their final action, a celebratory march through central London, took place last month. Mel Carrington, a JSO spokesperson, is bullish about the group’s achievements: “We won our demand, and we made the need to end new oil and gas a national talking point.” But she also acknowledges that the group failed to mobilise enough people to continue, and that the state crackdown on protest played its part in that: “To do street level actions you need a broad base of support. Since 2022, fewer and fewer people have mobilised, even for modest actions like slow marching. That’s the trend.”

While part of JSO will remain to support its many activists still trapped in the justice system, the bulk of the organisation will now metamorphosise into something new. And while Carrington is in dialogue with groups like Shut The System, and open-minded about their tactics, she is confident that JSO’s successor organisation will not adopt them. Again, the key issue with STS is their lack of accountability, and how that undermines JSO’s understanding of nonviolence. “Nonviolence uses disruption to create moments of tension and an emotional response, and accountability is an essential part of that,” she says. “As we don’t hide our faces or identities, we show that we are willing to stand up for what we believe in and to accept the legal consequences.” By ensuring actions are public displays of human vulnerability and courageous defiance, accountability is also a major catalyst for press attention. “Disruption, arrests and imprisonment are typically what drives our media coverage” continues Carrington.

While JSO and XR are both firmly wedded to accountability, they have very different takes on the virtues of disruption. On New Year’s Eve of 2022, XR renounced public disruption as a primary tactic, and started to prioritise attendance over arrests to stem waning participation post-pandemic. This led to ‘The Big One’ a few months later, a four-day rebellion outside the British parliament that was carefully marshalled by XR to minimise risk and maximise participation. And while The Big One did draw huge crowds, media interest was threadbare, the government ignored it, and it failed to match the impact of previous rebellions. Or as Carrington puts it: “XR got 90,000 onto the streets, but no one cared because it wasn’t challenging anything.”

Ecclestone gently refutes the idea that no one cared about The Big One, noting how XR collaborated with more than 200 organisations for the event, and how much hard work went into forging that grand alliance behind the scenes. For him, media coverage is not the only way to engage more of the population, and XR has no plans right now to go back to disrupting the public. “XR has remained consistent over the years. Our principles and values haven’t changed. We’ve always tried to be inclusive and accessible, and a home for everyone in the UK.”

What has changed for Ecclestone is police strategy. “In the 1990s, when I was policing protests against live animal exports, we had no interest in arresting the activists, or punishing them for blocking the trucks. We let them express their right to protest, and let the trucks get through with a minimum of fuss,” he says. “This new legislation is a way for police to abdicate their responsibility to enable peaceful protest. If you extinguish people’s right to protest, they’ll go to Shut The System to take it out on perpetrators directly rather than trying to persuade politicians.”

Although my STS contact will not be drawn into details, the group have big plans for this year, and they will not be alone in bringing sabotage to British streets. In February, another new climate group, Sabotage Oil for Survival, kicked off their campaign by drilling into the tyres of over 100 gas-guzzling SUVs across three Land Rover dealerships. Palestine Action will also continue to share knowledge and collaborate with Shut The System, and although there is no formal union between the two organisations, my contact describes the pro-Palestinian network as their “biggest inspiration.”

As for what this sabotage-filled future might mean for the rest of the climate movement, my STS contact focuses on the positives. They cite a recent academic study showing the “radical flank effect” of JSO, where that group’s disruptive actions made the moderate campaign of Friends of the Earth more popular. With global warming already exceeding 1.5°C, the Paris Agreement now a roadmap for a bygone era, and even the sober risk analysts of the insurance industry now warning that four billions lives could be lost by 2050, the belief that only moderate means can divert us from disaster feels increasingly delusional. If the climate movement adds sabotage to its arsenal, and breaking glass ends up breaking the political impasse, such actions should be seen not as sneaky sabotage, but heroic self-defence.

Berlin Blackout Attack On Industrial Park

It was “by no means our intention” to cut power to households, says communiqué, but to “turn off the juice to the military-industrial complex”

By Juju Alerta / FREEDOM NEWS Sep. 10th, 2025

Anarchists have taken responsibility for a major power outage in southeast Berlin early Tuesday, after two high-voltage pylons were set on fire in Johannisthal, Treptow-Köpenick.

The attack, which began around 3.30am according to police, cut electricity to some 43,000 households and 3,000 businesses. Entire areas were left without power, public transport was paralysed, traffic lights went dark, and mobile police units with loudspeaker vans were deployed to inform residents.

The state security division of the Berlin criminal police has taken over the investigation. A police spokesperson said arson was suspected and that a political motive “could not be ruled out”.

Later, a lengthy statement appeared on Indymedia in which a group of anarchists claimed the action, which they say targeted Adlershof technology park. The authors apologised to local residents for the blackout in private homes, saying this was “by no means our intention”, but described the collateral damage as “acceptable compared with the destruction of nature and the often deadly subjugation of people” caused by the targeted industries.

The communiqué singled out several companies, including Atos, Jenoptik, Siemens, and the German Aerospace Centre (DLR), accusing them of supplying militaries, enabling border surveillance and fuelling environmental destruction. “Their well-sounding slogans of innovation, sustainability and progress are nothing more than a manoeuvre on the battlefield of discourse, to cover up that they are actually building instruments that bring death and destruction”, the statement declared.

Tuesday’s fire is the most significant infrastructure sabotage in Berlin since a 2024 pylon attack cut power to Tesla’s Gigafactory in Grünheide.

In recent weeks there have also been attacks on vehicles and businesses linked to the landlord of Rigaer 94, a left-radical housing project which faces multiple court cases and eviction proceedings this month.

DGR News Service

Texte intégral (5500 mots)

Editor’s note: This is a difficult concept to understand. The reason is because we have been taught the opposite all our lives. Taxes don’t fund spending. The spending must be done first so that taxes can be paid. So it is not tax and spend, it is spend and tax. Our taxes don’t fund anything. That is why nobody asks how are we going to fund the military. Money is a government issued tax credit. Its value is derived from the violence that may be necessary to collect the tax. The government creates money by giving it to people for goods and/or services(guns or butter). Which then gives those people the ability to pay the tax. People accept the money out of fear of that violence. The tax collector has to be paid or promised to be paid before they perpetuate that violence(police). The money must be created first so that people can pay their taxes with it. It is spent into existence. Taxes create the necessity for money. A “deficit” just keeps score of how much extra money the government paid to people but was not collected as taxes. Much like beyond a certain point, how much money you have is just keeping score. The government cannot run out of its own money. Just like a baseball game has no limit on the score. What a government spends(creates) its money for are political decisions which are only constrained by the physical “resources” of the living planet.

Modern Monetary Theory

Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy

- The government must raise funds through taxation or borrowing in order to spend. In other words, government spending is limited by its ability to tax or borrow.

- With government deficits, we are leaving our debt burden to our children.

- Government budget deficits take away savings.

- Social Security is broken.

- The trade deficit is an unsustainable imbalance that takes away jobs and output.

- We need savings to provide the funds for investment.

- It’s a bad thing that higher deficits today mean higher taxes tomorrow.

How does civilization collapse? First slowly, then suddenly. Civilizational complexity solves human problems. – (Joseph Tainter) Maybe that is a solution in search of a problem. Never asking, just because we can does not mean that we should, e.g., technology, splitting the atom, agriculture.

The entire global money system in under 15 minutes

By Michael Hudson / WIKI Observatory

The pioneering research by one of the founders of economic anthropology is essential for understanding the social and institutional processes that gave rise to money as we know it.

The late 19th century saw economists, mainly German and Austrian, create a mythology of money’s origins that is still repeated in today’s textbooks. Money is said to have originated as just another commodity being bartered, with metal preferred because it is nonperishable (and hence amenable to being saved), supposedly standardized (despite fraud if not minted in temples), and thought to be easily divisible—as if silver could have been used for small marketplace exchanges, which was unrealistic given the rough character of ancient scales for weights of a few grams.[1]

This mythology does not recognize government as having played any role as a monetary innovator, sponsor, or regulator, or as giving money its value by accepting it as a vehicle to pay taxes, buy public services, or make religious contributions. Also downplayed is money’s function as a standard of value for denominating and paying debts.[2]

Although there is no empirical evidence for the commodity-barter origin myth, it has survived on purely hypothetical grounds because of its political bias that serves the anti-socialist Austrian school and subsequent “free market” creditor interests opposing government money creation.

Schurtz’s Treatment of Money as Part of the Overall Social System

As one of the founders of economic anthropology, Heinrich Schurtz approached the origins of money as being much more complex than the “economic” view that it emerged simply as a result of families going to the marketplace to barter. Surveying a wide range of Indigenous communities, his 1898 book, An Outline of the Origins of Money, described their trade and money in the context of the institutional system within which members sought status and wealth. Schurtz described these monetary systems as involving a wide array of social functions and dimensions, which today’s “economic” theorizing excludes as external to its analytic scope.

Placing money in the context of the community’s overall system of social organization, Schurtz warned that anyone who detaches “sociological and economic problems from the environment in which they emerged… their native land… only carries away a part of the whole organism and fails to understand the vital forces that have created and sustained it.”

Looking at Indigenous communities as having preserved presumably archaic traditions, Schurtz viewed trade with outsiders as leading wealth to take an increasingly monetary form that eroded the balance of internal social relations. Schurtz deemed the linkage between money, debt, and land tenure to lie beyond the area on which he focused, nor did he mention contributions to group feasts (which historian Bernard Laum suggested as the germ from which Greek obols and drachmas may have evolved).[3]

The paradigmatic forms of Indigenous wealth were jewelry and other items of personal adornment, decorations, and trophies, especially foreign exotic products in the form of shells and gemstones or items with a long and prestigious history that gave their wearers or owners status.

Thorstein Veblen would call the ownership and display of such items conspicuous consumption in his 1899 book, TheTheory of the Leisure Class. They had an exchange value, as they do today, but that did not make them monetary means of exchange. Schurtz saw many gray areas in their monetization: “Beads made of clay and stone are also crafted by Indigenous people and widely used as ornaments but rarely as money.”

At issue was how a money economy differs from barter and from the circulation and exchange of useful and valued items in a social economy. Was Indigenous exchange and wealth pre-monetary, an archaic seed that led to money’s “more ideal forms?”

Schurtz’s Distinction Between Inside-Money and Outside-Money

Exchange with outsiders was typically conducted by political leaders as the face of their communities to the outside world. Trade (and also payment of tribute) involved fiscal and social relations whose monetary functions differed from those of the domestic economy but ended up dovetailing with them to give money a hybrid character. Schurtz distinguished what he called outside-money from inside-money, with outside-money ultimately dominating the inside monetary system.

“The concept of money,” he wrote, originated “from two distinct sources: What functions as the foundation of wealth and measure of value for property and serves social ends within a tribe is, in its origins, something entirely different from the means of exchange that travels from tribe to tribe and eventually transforms itself, as a universally welcomed commodity, into a kind of currency.”

Inside-money was used within communities for their own exchange and wealth. Outside-money was derived from transactions with outsiders. And what was “outside” was a set of practices governing trade outside the jurisdiction of local governance.[4]

Schurtz’s distinction emphasized a characteristic of trade that has continued down through today’s world: the contrast between domestic payments subject to checks and balances to protect basic needs and navigating status hierarchies but (ideally) limiting sharp wealth disparities, and exchange with outsiders, often conducted on islands, quay areas, or other venues socially outside the community’s boundaries, subject to more impersonal standardized rules.

Throughout the ancient world, we find offshore island entrepots wherever they are conveniently located for conducting trade with outsiders.

These islands kept foreign contact at arm’s length to prevent mercantile relations from disturbing the local economic balance. Egypt restricted foreign contacts to the Delta region where the Nile flowed into the Mediterranean. For the Etruscans, the island of Ischia/Pithekoussai became the base for Phoenician and Greek merchants to deal with the Italian mainland in the eighth and seventh centuries BCE. North Germans seem to have conducted the Baltic amber trade through the sacred island of Helgoland.

“The emergence of specific internal monetary systems is always supported by the inclination to transform outside-money into inside-money, and to employ money not to facilitate external trade, as one might assume according to common theories, but rather to obstruct it,” Schurtz concluded. In his chapter, “Metal as Ornament and Money,” he pointed out that it was foreign trade that led metal to become the primary form of money. “While most varieties of ornament-money gradually lose their significance, one of them, metal-money, asserts its ground all the more and finally pushes its competitors out of the field.” He added that: “Metal-money made from noble metals is not a pure sign-money, it is at the same time a valuable commodity, the value of which depends on supply and demand. In its mature form, it therefore in itself embodies the fusion of inside-money with outside-money, of the sign of value and valuable property with the means of exchange.”[5]

This merging of inside- and outside-money is documented already in the third millennium BCE in the Near East. Silver-money was used for long-distance trade and came to be used for domestic enterprise as well, while grain remained the monetary vehicle for denominating agrarian production, taxes, and debt service on the land, and for distribution to dependent labor in Mesopotamia’s temples and palaces.

Schurtz also questioned whether the dominance of metallic money emerged spontaneously in many places or whether there was a diffusion from a singular origin, that is, “whether a cultural institution has grown in situ or whether it has been transferred from other regions through migration and contact between societies.” The diffusion of Mesopotamian weights is associated with silver points to its diffusion from that region, as does the spread of the region’s practice of setting interest rates simply for ease of calculation in terms of the local fractional arithmetic system (60ths in Mesopotamia for a shekel per mina a month, 10ths or percentages in decimalized Greece, and 12ths in Rome for a troy ounce per pound each year).

Checks and Balances to Prevent the Selfish Concentration of Wealth

What does seem to have developed spontaneously were social attitudes and policies to prevent the concentration of wealth from injuring economic balance. Wealth concentration, especially when achieved by depriving cultivators of their means of livelihood, would have violated the ethic of mutual aid that low-surplus economies need as a condition for their resilience.

Viewing money as part of the overall social context, Schurtz described “the social transformation brought about by wealth” as a result of monetizing trade and its commercial pursuit of profit, or “acquisitiveness”:

“[E]veryone is now compelled to join in the competition for property or he will be pulled into the vortex created by one of the newly emerging centers of power and property, where he will need to work hard to be able to live at all. For the property owner, no temporal limit constrains his view on the perpetual increase of his wealth.”

Schurtz characterized the economic mentality as a drive for “the unlimited accumulation of movable property,” to be passed on to one’s children, leading to the creation of a wealthy hereditary class. If archaic societies had this ethic, could ancient civilizations have taken off? How did they prevent the growth of wealth from fostering an oligarchy seeking to increase its wealth at the expense of the community at large and its resilience?

Schurtz reviewed how Indigenous communities typically avoided that fate by shaping a social value system that would steer wealth away from being used to achieve predatory power over others. He cited numerous examples in which “immense treasures often accumulate without reentering the transactions of daily life.” One widespread way to do this was simply to bury wealth. “The primitive man,” he wrote, “believes that he will have access to all the goods given to him in the grave, even in the afterlife. Thus, he too knows no bounds to acquisition.”

Taking his greed and wealth with him to use in the hereafter prevents hoarded wealth from being inherited “and growing into a dangerous instrument of power” by becoming dynastic; ultimately operating “on the belief that the deceased does not give up his rights of ownership but jealously guards over his property to ensure that no heir makes use of it.” A less destructive removal of wealth from its owners was to create an ethic of peer pressure in which individuals gained status and popular acclaim by accumulating wealth to give away. Schurtz wrote:

“[R]emnants of the ancient communism remain alive enough for a long time to effectively block attempts to amass as many assets as possible in a single hand. And in places without an actual system of debt and interest, the powerful individual, into whose house the tributes of the people flow, has indeed little choice but to ‘represent’ by way of his wealth: in other words, to allow the people to participate in his indulgences.”

Such an individual achieves philanthropic renown by generously distributing his possessions to “his friends and followers, winning their hearts and thereby establishing real power based on loyal devotion.” One widespread practice was to celebrate marriages, funerals, and other rites of passage by providing great feasts. This “extraordinary… destruction and squandering of valuable property, particularly livestock and food, during those grand festivals of the dead that evolved out of sacrifices and are, among some peoples, not only an effective obstacle to the accumulation of wealth but have turned into economic calamities” when families feel obliged to take on debt to host such extravagant displays.

Religious officials and temples often played a role in such rituals. Noting that “money, trade, and religion had a good relationship with one another in antiquity,” Schurtz cited the practice of donating wealth to temples or their priesthoods. But he recognized that this might enable them to “gain dominance through the ownership of money” under their control.

“The communist countermeasures against wealth generally do not endure,” Schurtz wrote. “Certain kinds of property seem to favor greed directly, especially cattle farming, which can literally turn into a hoarding addiction.” He described communalistic values of mutual aid as tending to break down as economies polarized with the increase in commercial wealth.

Schurtz also noted that the social checks on personal wealth-seeking did not apply to economies that developed a “system of debt and interest.” Wealth in the form of monetary claims on debtors was not buried and could hardly be redistributed to the population at large, whose members typically were debtors to the rising creditor interest.

The only way to prevent such debts from polarizing society was to cancel them. That is what Near Eastern rulers did, but Schurtz’s generation had no way of knowing about their Clean Slate proclamations.

Starting with the very outset of debt records c. 2500 BCE in Sumer, and continuing down through Babylonia, Assyria, to their neighbors, and on through the early first millennium BCE, rulers annulled financial claims on agrarian debtors. That prevented creditors from concentrating money and land in their own hands. One might say that these debt cancellations and land redistributions were the Near Eastern alternative to destroying material wealth to preserve balance. These royal acts did not destroy physical wealth but simply wiped out the debt overhead to maintain widespread land tenure and liberty for the population at large.

Canceling agrarian debt was politically feasible because most personal debts were owed to the palace sector and its temples or their officials. Royal Clean Slates seemed so unthinkable when they began to be translated around the turn of the last century that early readers hardly could believe that they actually were enforced in practice. François Thureau-Dangin’s French translation of the Sumerian ruler Enmetena’s (c. 2400 BCE) proclamation in 1905 was believed by many observers to be too utopian and socially disruptive to have been followed in practice, as was the Biblical Jubilee Year of Leviticus 25.[6]

But so many such proclamations have been found, extending so continuously over thousands of years—along with lawsuits in which judges upheld their increasing detail—that there is no doubt that these acts did indeed reconcile the accumulation of monetary wealth with social resilience by blocking the creation of predatory oligarchies such as those that would emerge in classical Greece and Rome and indeed survive into today’s world.

Monetary Innovations in the Bronze Age Near Eastern Palaces and Temples

Economic documentation in Schurtz’s day was able to trace monetary practice only as far back as classical Greece and Rome. There was a general belief that their practices must have evolved from Indigenous Indo-European speakers. Marcel Mauss would soon treat the gift exchange of the Kwakiutl tribe of the Canadian Pacific Northwest (with their competitive one-upmanship) as the prototype for the idea of charging interest. But monetary interest has a specific stipulated rate, with payments due on specific periodic dates set by written contracts. That practice stems from Sumer in the third millennium BCE, along with silver (and grain) money and related financial innovations in the economic big bang that has shaped subsequent Western economic evolution.

Money’s function as a standard of valuation did not play a big role in Schurtz’s survey. But subsequent archaeological research has revealed that money’s emergence as part of an overall institutional framework cannot be understood without reference to written account-keeping, denominating debt accruals, and fiscal relations. Money, credit/debt, and fiscal obligations have all gone together since the origins of written records in the ancient Near East.

Near Eastern fiscal and financial records describe a development of money, credit, and interest-bearing debt that neither the barter theory nor Schurtz’s ethnographic studies had imagined. Mesopotamia’s “more ideal” money evolved out of the fiscal organization of account-keeping and credit in the palaces and temples of Sumer, Babylonia, and their Bronze Age neighbors (3200–1200 BCE). These Near Eastern economies were larger in scale and much more complex and multilayered than most of the Indigenous communities surveyed by Schurtz.

In contrast to largely self-sufficient communities, southern Mesopotamia was obliged to engage in large-scale and long-distance trade because the region’s river-deposited soil lacked metal, stone, and even hardwood. The region’s need for raw materials was far different from the trade and “monetization” of luxuries by the relatively small-scale and self-sufficient communities studied by Schurtz and hypothesized by economists imagining individuals bartering at their local market. In these communities, he noted: “The amount of metal shaped into ornaments almost always far outweighs the amount transformed into practical tools.” Mesopotamia’s trade had to go far beyond personal decorative luxuries and prestige commodities or trophy items.

An entrepreneurial merchant class was needed to obtain these raw materials, along with a specialized labor force, which was employed by the temples and palaces that produced most export handicrafts, provisioned corvée labor to work on public infrastructure, served as mints and overseers of weights and measures, and mediated most monetary wealth and debt. This required forward planning and account-keeping to feed and supply labor (war widows, orphans, and slaves) in their weaving and other handicraft workshops and to consign their output to merchants for export. Calculating the cost of distributing food and raw materials within these large institutions and valuing their consignment of goods to merchants required designing standard weights and measures as the basis for this forward planning. Selecting monetary units was part of this standardization of measuring costs and value.

This made possible the calculation of expected rental income or shortfalls, along with profit-and-loss statements and balance sheets. The typical commodity to be distributed was grain, which served as a standard of value for agrarian transactions and credit balances that mounted up during the crop year for advances to sharecroppers, consumption such as beer from ale-women, and payments to priests for performing ceremonial functions. Their value in grain was to be paid at harvest time.

The calculation of food rations for distribution to the various grades of labor (male, female, and children) enabled the costs to be expressed in grain or in workday equivalents.

Schurtz would have called this grain “inside-money,” and regarded as “outside-money” the silver minted by temples for dealing with foreign trade and as the basic measure of value for business transactions with the palace economy and for settling commercial obligations. A mina (60 shekels) of silver was set as equal to a corresponding unit of grain as measured on the threshing floor. That enabled accounts to be kept simultaneously in silver and grain.

The result was a bi-monetary grain-silver standard reflecting the bifurcation of early Mesopotamian economies between the agrarian families on the land (using grain as “inside-money”) and the palatial economy with its workshops, foreign trade, and associated commercial enterprise (using silver as “outside-money”).

Prices for market transactions with outsiders might vary, but prices for debt payments, taxes, and other transactions with large institutions were fixed.

Schurtz’s conclusion that the rising dominance of commercial money tended to break down domestic checks and balances protecting the Indigenous communities that he studied is indeed what happened when commercial debt practices were brought from the Near East to the Aegean and Mediterranean lands around the eighth century BCE.

Having no tradition of royal debt cancellations as had existed in the Near East ever since the formative period of interest-bearing debt, the resulting decontextualization of credit practices fostered financial oligarchies in classical Greece and Rome. After early debt cancellations and land redistribution by populist “tyrants” in the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, the ensuing classical oligarchies resisted popular revolts demanding a revival of such policies.

The dynamics of interest-bearing debt and the pro-creditor debt laws of classical antiquity’s creditor oligarchies caused economic polarization that led to five centuries of civil warfare. These upheavals were not the result of the coinage that began to be minted around the eighth century BCE, as many 19th-century observers believed, mistakenly thinking that Aegean coinage was the first metallic money. Silver-money had been the norm for two millennia throughout the Near East, without causing disruption like that experienced by classical antiquity. What polarized classical antiquity’s economies were pro-creditor debt laws backed by political violence, not money.

Conclusion and Discussion

Schurtz’s starting point was how communities organized the laws of motion governing their distribution of wealth and property. He viewed money as emerging from this institutional function with a basically communalistic ethic. A key characteristic of Indigenous economic resilience was social pressure expecting the wealthy to contribute to social support. That was the condition set by unwritten customs for letting some individuals and their families become rich.

Schurtz and subsequent ethnologists found a universal solution for reconciling wealth-seeking with community-wide prosperity to be social pressure for wealthy families (that was the basic unit, not individuals) to distribute their wealth to the citizenry by reciprocal exchange, gift-giving, mutual aid, and other forms of redistribution, and providing large feasts, especially for rites of passage.

This was a much broader view than the individualistic economic assumption that personal gain-seeking and, indeed, selfishness were the driving forces of overall prosperity. The idea of monetizing economic life under communalistic mutual aid or palace direction was and remains anathema to mainstream economists, reflecting the worldview of modern creditors and financial elites. Schurtz recognized that mercantile wealth-seeking required checks and balances to prevent economies from impoverishing their members.

The problem for any successfully growing society to solve was how to prevent the undue concentration of wealth obtained by exploitative means that impaired overall welfare and the ability of community members to be self-supporting. Otherwise, economic polarization and dependency would lead members to flee from the community, or perhaps it simply would shrink and end up being defeated by outsiders who sustained themselves by more successful mutual aid.

As noted above, Schurtz treated the monetization of wealth in the form of creditor claims on debtors as too post-archaic to be a characteristic of his ethnographic subjects. But what shaped the context for monetization and led “outside-money” to take priority over inside-money were wealth accumulation by moneylending and the fiscal and military uses of money. Schurtz correctly rejected Bruno Hildebrand’s characterization of money as developing in stages, from small-scale barter to monetized economies becoming more sophisticated as they evolved into financialized credit economies.[7]

And, in fact, the actual historical sequence was the reverse. From Mesopotamia to medieval Europe, agrarian economies operated on credit during the crop year. Monetary payment occurred at harvest time to settle the obligations that had accumulated since the last harvest and to pay taxes. This need to pay debts was a major factor requiring money’s development in the first place. Barter became antiquity’s final monetary “stage” as Rome’s economy collapsed after its creditor oligarchy imposed debt bondage and took control of the land.

When emperors were unable to tax this oligarchy, they debased the coinage, and life throughout the empire devolved into local subsistence production and quasi-barter. Foreign trade was mainly for luxuries brought by Arabs and other Near Easterners. The optimistic sequence that Hildebrand imagined not only mistakenly adopted the barter myth of monetary origins but also failed to take debt polarization into account as economies became monetarized and financialized.

Schurtz described how the aim of preventing the maldistribution of wealth was at the heart of Indigenous social structuring. But it broke down for various reasons. Economies in which family wealth took the form of cattle, he found, tended to become increasingly oppressive to maintain the polarizing inequality that developed. The same might be said of credit economies under the rising burden of interest-bearing debt. Schurtz noted the practice of charging debtors double the loan value—and any rate of interest indeed involves an implicit doubling time.

That exponential dynamic is what polarizes financialized economies. In contrast to Schurtz, mainstream economists of his generation avoided dealing with the effect of monetary innovation and debt on the distribution of wealth. The tendency was to treat money as merely a “veil” of price changes for goods and services, without analyzing how credit polarizes the economy’s balance sheet of assets and debt liabilities. Yet, the distinguishing feature of credit economies was the use of moneylending as a lever to enrich creditors by impoverishing debtors. That was more than just a monetary problem. It was a political creditor/debtor problem and, ultimately, a public/private problem.

The issue was whether a ruler or civic public checks would steer the rise in monetary wealth in ways that avoided the creation of creditor oligarchies.

Most 19th-century and even subsequent economic writers shied away from confronting this political context, leaving the most glaring gap in modern economic analysis. It was left to the discovery of cuneiform documentation to understand how money first became institutionalized as a vehicle to pay debts. This monetization was accompanied by remarkable success in sustaining rising wealth while preventing its concentration in the hands of a hereditary oligarchy. That Near Eastern success highlights what the smaller and more anarchic Western economies failed to achieve when interest-bearing debt practices were brought to the Mediterranean lands without being checked by the tradition of regular cancellation of personal nonbusiness debt.

Credit and monetary wealth were privatized in the hands of what became an increasingly self-destructive set of classical oligarchies culminating in that of Rome, which fought for centuries against popular revolts seeking protection from impoverishing economic polarization.

The devastating effects of transplanting Near Eastern debt practices into the Mediterranean world’s less communalistic groupings show the need to discuss the political, fiscal, and social-moral context for money and debt. Schurtz placed monetary analysis in the context of society’s political institutions and moral values and explained how money is a product of this context and, indeed, how monetization tends to transform it—in a way that tends to break down social protection. His book has remained relatively unknown over the last century, largely because his institutional anthropological perspective is too broad for an economics discipline that has been narrowed by pro-creditor ideologues who have applauded the “free market” destruction of social regulation aimed at protecting the interests of debtors.

That attitude avoids recognizing the challenges that led the Indigenous communities studied by Schurtz, and also the formative Bronze Age Near East, to protect their resilience against the concentration of wealth, a phenomenon that has plagued economies ever since classical antiquity’s decontextualization of Near Eastern debt practices.

Banner Photo by Towfiqu barbhuiya on Unsplash

DGR News Service

Texte intégral (2737 mots)

Editor’s note: “President Donald Trump has been pushing the U.S. to barrel ahead on deep-sea mining. The country plans to permit mining in international waters under an obscure U.S. law from 1980 called the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act(DSHMRA), which predates the Law of the Sea treaty. Congress wrote the law to serve as an ‘interim legal regime’ — a temporary way to grant mining licenses until the United Nations-affiliated regime took shape.

A main point of contention is that, according to the U.N. treaty and the DSHMRA, the international seabed is designated the ‘common heritage of mankind.’ In other words, the nodules legally belong to all people living on Earth today as well as future generations. The treaty declares that any profits from exploiting that heritage be distributed across nations, not just reaped by one country, in a benefits-sharing agreement that treaty signatories are still hashing out

The French diplomat slammed the Trump administration’s executive order, issued on April 24, that directs the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration(NOAA) to fast-track seabed exploration and commercial mining permits in both U.S. waters and ocean areas beyond America’s jurisdiction — commonly called the high seas..”

Invoking national security to justify private sector economic development is a tired cliché. And yet, in a troubling twist, a Canadian company is invoking U.S. national security to obtain an exclusive license from the U.S. government for a deep-sea mining venture for critical minerals in international waters—and it appears to be working.

Companies leading the push to launch deep-sea mining under a U.S. license are foreign-incorporated entities with no operational footprint—and no meaningful supply chain commitments to it. The timeline for commercial production remains uncertain and subject to indefinite delays due to technical, financial, and regulatory hurdles.

Far from offering strategic value, this initiative is best understood as a speculative venture propped up by shifting political winds. Deep-sea mining is not the answer to a mineral security crisis—it’s a solution to a problem that does not exist.

Public comments on the proposed NOAA rule must be received by September 5, 2025. Submit all public comments via the Federal e-Rulemaking Portal at https://www.regulations.gov/docket/NOAA-NOS-2025-0108/document?withinCommentPeriod=true

NOAA will hold two virtual public hearings, on September 3, 2025, and on September 4, 2025, to receive oral comments on the July 7, 2025, proposed rule for revisions to the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act (DSHMRA or the Act) regulations. Registration is required https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/08/04/2025-14657/deep-seabed-mining-revisions-to-regulations-for-exploration-license-and-commercial-recovery-permit

At the very least, ask for a 60 day extension to the public comment period because of the crucial nature of the proposal. But also express that you strongly oppose consolidating the exploration license and commercial recovery permit process.

Mining in international waters without global consent carries enormous reputational, legal, and financial risks. It could trigger investor pullout, international condemnation, and logistical nightmares. We can make sure it’s simply not worth the cost.

Despite everything, I left Jamaica feeling positive. Progress might be slow, yet things are moving in the right direction. But we can’t afford complacency. This meeting made clear just how fragile international governance really is. Loopholes and silence are letting corporate interests push the system to its limits.