Facing floods in one of the world’s fastest-sinking cities is how I found out that the climate crisis is tougher on women

Kezia Rynita

On 8 March 2026, many neighbourhoods in Jakarta – one of the fastest-sinking cities in the world – were submerged by floods. Hundreds of residents displaced as relentless rainfall hit the metropolitan area and its satellite cities, including Bekasi, the one where I live now. These floods happening exactly on International Women’s Day instantly reminded me of how I learned that the climate crisis is tougher on women. I know people don’t tend to think about gender when they think about extreme weather events, but the evidence shows that it’s connected. And as a woman who experienced countless floods in Jakarta, I can testify: the climate crisis is not just. It’s not gender-neutral. I didn’t figure it out by accident. When I was a teenager, life took an unexpected turn from what it used to be. Certain situations forced our family to let go of our childhood home and move to a densely-populated neighbourhood in one of the city’s alleys where reliable electricity was sometimes a luxury. We found out too late that it was also a flood-prone area until one morning, it came. We didn’t get the opportunity to evaluate that sudden risk. My Dad and my little brother immediately laid some old clothes near our front door as barriers, while my Mom and I put our family’s important papers and documents in the cheap waterproof bags. We tried our best to avoid the water from entering without sandbags, but we failed. Most of the house was submerged. No clean water. No electricity. No access to buy food. We slowly became familiar with such conditions as floods kept coming again and again occasionally during rainy seasons. As a teenage girl, I was often frustrated because I wasn’t able to buy sanitation supplies when I needed them the most, including menstrual pads. It never crossed my mind that dealing with numerous floods without proper resources while facing significant infrastructural and social challenges in Jakarta – with myriad threats like tidal floods, rising sea levels, water scarcity, and poor air quality – meant my health and hygiene were being compromised. I didn’t have time to miss my childhood home. I talked to my female neighbours in that area during those years. Some of them were middle school students like me, some were single mothers whose children were sick from time to time due to constant flooding and polluted air, some were informal middle-aged workers with low-paid wages to support the family, and one of them even told me she had to suffer from domestic violence in the past as a result of increasing stress levels in the similar neighbourhood. All of us collectively agreed the same thing: when people romanticised the rain, we wholeheartedly cursed it. This memory which I once denied has become a part of my own story. I soon realised there are many other women exposed to environmental risks in Jakarta whose struggles are even made harder due to poverty, cultural norms, gendered-responsibilities, and systematically unjust oppression. The climate crisis disproportionately affects women who are already dealing with stigma and discrimination they are up against in their daily life, especially when they are also a part of other marginalised groups: low-income, BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color), disabled, or LGBTQ+, exposing the intersectionality of climate impacts, gender inequality and social injustice. In some regions, women already lack access to healthcare, basic education, natural resources, or employment, making them less prepared than men when the climate disasters hit. The Indigenous Women communities in Brazilian Amazon have to spend more time in their fields to secure minimal harvests or walk longer distances to collect water when rivers run dry while they have to take care of family members who are sick due to the rising temperatures. Their burdens have physically and mentally multiplied. Another fact that the relationship between women and the climate crisis has often been overlooked is that the effects of the crisis are intensifying the social and economic stresses that are contributing to violence against women and girls, just like what one of my former neighbours experienced above. Many women in Indonesia also have to face systematic violence from authorities as the exploitative management of natural resources which constantly causes climate disasters often uses methods that violate human rights. Gender gaps in climate policy-making still persist across the world. Women make up less than 40% of environment ministers in wealthier societies, and the numbers are even considerably lower in locations where women are most vulnerable to environmental risk, particularly in low-income countries and environmentally-sensitive sectors. As much as I support and encourage the acts of solidarity during women’s history month in which I was a part of as well, I think we need to remind ourselves that it’s important we should recognise and stand in solidarity with women who have enough resources and successfully thrive in male-dominated fields, but especially with women in minorities and those at the forefront of the climate crisis, such as single mothers in coastal communities without free access to healthcare and have low-paid jobs, Indigenous women whose efforts are central to our planet’s biodiversity, or women human rights defenders experiencing intimidation and violence. A better understanding on how gender equality intersects with social and climate justice plays a key role in order to call for real actions and implement solutions that work for our varied experiences. When gender equality is treated as a symbolic celebration, it’s only a decoration. It’s time for actual representation and inclusion that ensures women’s voices are heard and their struggles are properly addressed. Social justice and climate justice are about our planet and the lives of all people, so fighting for both is crucial to achieve a fairer, greener, more equitable, and more sustainable future for all. Texte intégral (1638 mots)

The burden of the climate crisis is not evenly distributed

Women are more at risk, but less in policy-making roles

Greenpeace Pictures of the Week

Greenpeace International

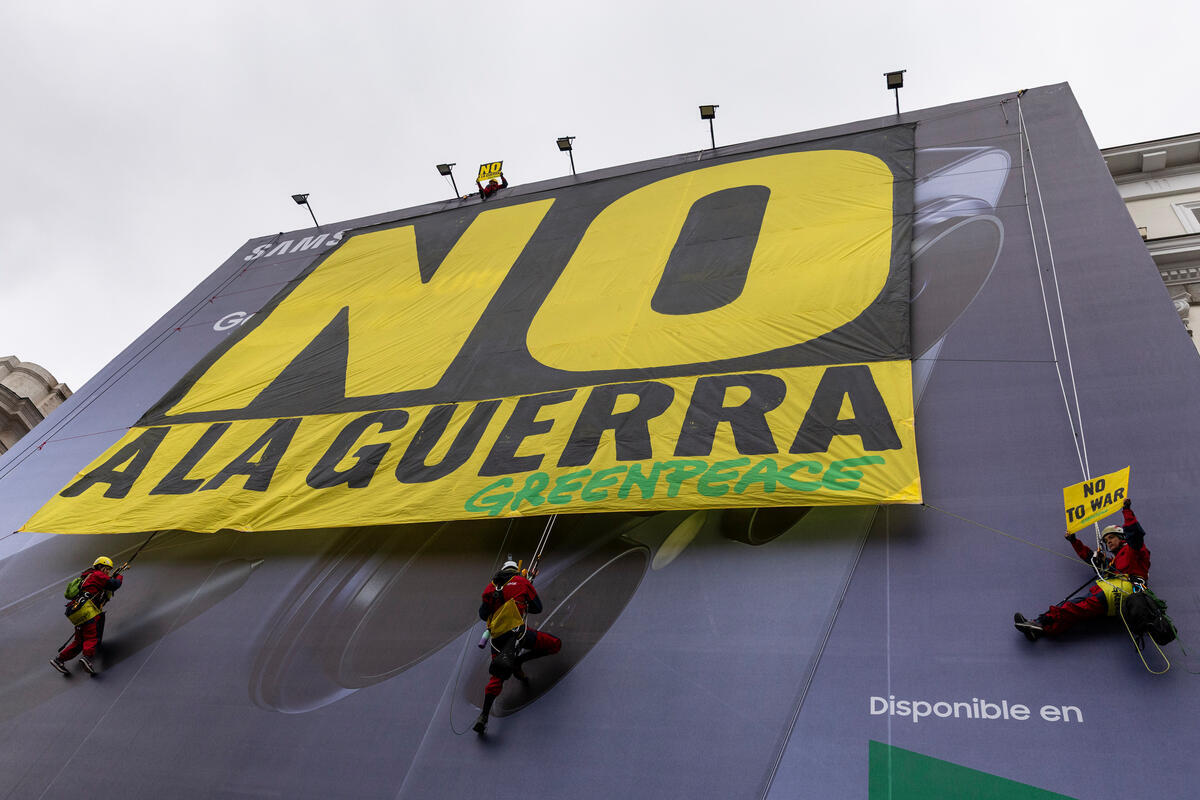

No more bombs, no nukes, no more bullies. Here are a few of our favorite images from Greenpeace work this week. Comment below which you like best! Spain – Greenpeace Spain activists unfurled a giant banner with the message “NO TO WAR” in Madrid’s Puerta del Sol, one of the city’s most iconic locations, to send a clear message to world leaders: war is never the solution. Switzerland – Greenpeace Switzerland activists draw a circle with a red thread 5 kilometres around the Gösgen nuclear power plant on Saturday. In doing so, they illustrate the drastic loss of living, residential and working space following a nuclear accident – knowing that a reactor disaster could affect an even larger area. Indonesia – Sinta Gebze, a Malind Indigenous community member whose story is featured in the film Pig Feast (Pesta Babi), embraces one of the participants after sharing her response and watching the film in Jayapura, Papua. Belgium – Thousands of protesters march in Brussels on International Women’s Day to demand gender equality, protesting issues like gender-based violence, wage gaps, and supporting reproductive rights. France – Greenpeace France activists disrupted the arrival of official delegations at the World Nuclear Summit. Greenpeace has been a pioneer of photo activism for more than 50 years, and remains committed to bearing witness and exposing environmental injustice through the images we capture. To see more Greenpeace photos and videos, visit our Media Library. Texte intégral (1050 mots)

Greenpeace reaction to the Unilever Annual Report 2025

Greenpeace International

Amsterdam, Netherlands – Unilever released its Annual Report and Accounts 2025 which reviewed the company’s progress on packaging sustainability and outlined plastic-specific targets on virgin plastic reduction and packaging types including flexibles or sachets. In response, Graham Forbes, Global Plastics Campaign Lead, Greenpeace USA said: “Unilever’s latest sustainability targets fail once again to match the scope of its plastic problem, or provide clarity for its shareholders and customers on how it will end its plastic sachet disaster. Swapping some sachets for paper alternatives is a false solution and does little to address the urgency and scale of the packaging waste and pollution crisis it helped create. Unilever is replacing one single-use material with another rather than tackling the root cause of plastic pollution.” “Millions of plastic sachets continue to be produced every day, many ending up polluting communities and waterways across the Global South. Brands like Dove are among those contributing to this flood of single-use packaging, leaving communities to deal with the consequences of waste they did not create.” “As one of the world’s largest consumer goods companies Unilever has both the responsibility and the ability to lead the shift away from single-use packaging towards reuse solutions. Greenpeace is calling on Unilever to create a clear roadmap to phase out all single-use sachets and scale up reuse systems. Real leadership will bring an end to the company’s dependence on plastic packaging and support a strong Global Plastics Treaty that cuts plastic production at the source.” ENDS Contacts: Angelica Carballo Pago, Global Plastics Communication and Media Lead, Greenpeace USA, +63917 1124492, apago@greenpeace.org Greenpeace International Press Desk, +31 (0) 20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org (319 mots)

Greenpeace warns of ‘disaster waiting to happen’ as 85 large oil tankers lie trapped in the Persian Gulf

Greenpeace International

Strait of Hormuz – Responding to news of escalating attacks by Iran on vessels stuck in the Persian Gulf extending to the Strait of Hormuz, Nina Noelle at Greenpeace Germany, which has been mapping oil tankers trapped in the area and potential impacts of an oil spill, said: “Right now, there are dozens of tankers carrying billions of litres of oil trapped in the Persian Gulf as mines are being laid and missiles are hitting ships. This is an environmental disaster waiting to happen. A single oil spill in the Gulf could damage this fragile marine habitat beyond repair with devastating consequences for people, animals, and plants in the region, adding to the terrible human toll this illegal war has already taken on local communities. “The US-Israel attack on Iran and subsequent strikes by Iran on neighbouring Gulf countries has shown once again that our dependence on fossil fuels is a constant threat to peace, security and prosperity. When oil and gas prices surge, fossil fuel giants rake in more profits while everyday people are hit by higher costs for heating, electricity, transport and food. “Greenpeace is calling on all parties to de-escalate tensions and pursue peaceful, diplomatic solutions and on governments everywhere to urgently shift away from fossil fuels towards distributed renewable energy systems where the risks of conflict are reduced rather than amplified. “From Venezuela to Iran, we’ve seen how Trump’s stated desire to control resources – especially oil and gas – is playing out in violent foreign policy. In Trump’s illegal war with Iran, the only winners are the oil and gas companies.” An investigation by Greenpeace Germany has analysed the blocked Strait of Hormuz using ship movement data and satellite imagery and simulated the potential consequences of oil spills in the Persian Gulf if tankers are damaged. At present, the oil tankers trapped in the Persian Gulf are carrying at least 21 billion litres of oil. “Greenpeace simulations show how an oil slick could spread if the stranded tankers are damaged in an attack. The Strait of Hormuz and adjacent waters are home to pristine coral reefs, mangrove forests, and seagrass meadows. This is an ecological ticking time bomb and represents an enormous risk that further increases instability and human suffering in the region.” ENDS Satellite images available for download via the Greenpeace Media Library. Link to interactive map Notes: [1] Greenpeace Germany is tracking larger oil tankers above 80.000 DWT (deadweight tonnage) and 100 metres length. Interactive map and accompanying article: How oil tankers stuck in the Strait of Hormuz south of Iran threatens the Gulf ecosystem [2] You can’t blow up the sun: 4 reasons renewables are a security imperative [3] In Trump’s illegal war with Iran, the only winners are the oil and gas companies Contacts: Nina Noelle, crisis communications and international relations manager, Greenpeace Germany, +49 151 10622733, nina.noelle@greenpeace.org Greenpeace International Press Desk, +31 (0)20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org Texte intégral (618 mots)

🌱 Bon Pote

Actu-Environnement

Amis de la Terre

Aspas

Biodiversité-sous-nos-pieds

🌱 Bloom

Canopée

Décroissance (la)

Deep Green Resistance

Déroute des routes

Faîte et Racines

🌱 Fracas

F.N.E (AURA)

Greenpeace Fr

JNE

La Relève et la Peste

La Terre

Le Lierre

Le Sauvage

Low-Tech Mag.

Motus & Langue pendue

Mountain Wilderness

Negawatt

🌱 Observatoire de l'Anthropocène