17.01.2023 à 23:07

Living in Freedom: Notes on Colectivo Situaciones and MTD Solano’s Hypothesis 891

Today, when the term “militant research” is regularly used in academic articles and texts, it is worth returning to the question of the purpose and practice of research militancy. Ultimately, as Hipotesis 891 highlights, research militancy is not primarily about another way of doing research, or least research that assumes academia as its main site of enunciation. Rather, it is about another way of doing politics, that does not follow a predetermined line or presume to know the answers a priori, but that sees research as part of the political process itself.

The post Living in Freedom: Notes on Colectivo Situaciones and MTD Solano’s <i>Hypothesis 891</i> appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

Texte intégral (4820 mots)

Hypothesis 891 presents precisely that, a series of situated hypotheses (the number comes from the street address where those hypotheses were elaborated). It also showcases the process through which those hypotheses were proposed, discussed, tested, challenged, accepted or discarded. In other words, it does not present answers, but a way of asking questions. It is in this sense that it represents a process of “militant research” or “research militancy.” These texts were part of a series of workshops held with members of the militant research collective Colectivo Situaciones and members of the Movimiento de Trabajadores Desocupados [Unemployed Workers’ Movement, MTD] of Solano. At the time, Colectivo Situaciones consisted of a group of university students who had become frustrated both with the dominant forms of leftist activism and academic knowledge. In search of a form of knowledge immanent to struggles, that did not separate the object from the subject of knowledge production, they began working with the series of innovative social movements emerging in Argentina to collectively reflect on and theorize the moment, recognizing, in turn, that this knowledge is itself a productive force that intervenes in the situation at hand. The work presented here brings Colectivo Situaciones into dialogue with one of the most innovative movements of the unemployed at the time: the MTD of Solano. The MTD of Solano was already developing its own conceptions of autonomy, power, neighborhood organizing, alternative economies, the production of subjectivity, the meaning of freedom. The confluence between the two groups thus produced an immensely rich dialogue, which extended well beyond the production of this book.

The texts that make up this book include initial hypotheses, written by Colectivo Situaciones, edited transcripts of the conversations in the workshops discussing the hypotheses, and response pieces by both Colectivo Situaciones and the MTD of Solano. The book, as a whole, is the result of a process of collective thought and elaboration, both by each group on its own – Colectivo Situaciones and the MTD of Solano – and together through the workshop discussions where the words of members of each collective are woven together, to create new understandings and analyses that could not have emerged from either collective alone. The texts thus reflect tensions, both between and within the collectives, and also elaborations on those tensions as the thinking changes over time.

The workshops that provided the material for this book took place between September 2001 and August 2002, during which time Argentina saw one of the most important processes of resistance to neoliberal capitalism that the world had seen at that time, effectively overthrowing the neoliberal government in December 2001. That uprising was led by many of the movements and organizations discussed in this book – the movements of the unemployed, neighborhood assemblies, and barter networks – yet it also exceeded and went far beyond those existing forms of organizing. It drew all sorts of people into the streets, despite the state of emergency and curfew declared by the government. Those people, whether in organizations or not, protested, set up barricades and fought off the police and military, until the president, Fernando de la Rúa, abandoned his office. This led to a time of intense social experimentation, both in forms of political organization and in forms of researching and thinking, of which this book is a prime example.

“A movement of movements”: The Unemployed Workers’ Organizations

By the late 1990s, Argentina was experiencing a severe economic crisis: years of neoliberal structural adjustment, demanded by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, had failed and poverty and unemployment were reaching record levels. It was in this context that the unemployed began organizing. At first derided and ignored by the major labor union federations and leftist parties alike, the unemployed began organizing autonomously, initially coming together around shared problems of social reproduction – unpayable electricity and gas bills, the rising cost of food, health care, and education – and mass job loss. In smaller cities in the interior of the country, such as Cultral-Co, whole communities came together after mass layoffs at the recently privatized oil company YPF. These uprisings – known as pueblazos for the way the whole community participated – were fundamental in bringing the issue of unemployment into the public agenda and popularizing the tactic of the roadblock (piquete). As the unemployed began organizing around the country, from those smaller cities to the urban peripheries of major metropolises such as Buenos Aires, La Plata, and Rosario, the tactic of the roadblock became the tool of choice for the unemployed. This is what led to the organized unemployed being baptized as piqueteros.1 Organizations of the unemployed – piqueterxs – thus started organizing roadblocks around the country, blockading major highways, bridges, and other key transit points, sometimes for weeks at a time. Those roadblocks brought the circulation of commodities to a halt and forced different levels of government to start responding to the piqueterxs demands for unemployment insurance, food aid, etc. The roadblocks, at least in some cases, were also a space for what the MTD of Solano refers to as the construction of a “new sociality,” producing new ways of living together that challenge the dominant capitalist subjectivity.

Despite this shared tactic and common problems, the different organizations of the unemployed that emerged in different territories were extremely diverse, with different compositions, adopting different ideological positions and organizational forms, and making different alliances. As the political power of the unemployed became clear, labor unions and leftist parties also started their own unemployed branches or tried to bring existing unemployed organizations into their fold. And yet other unemployed organizations remained “autonomous,” unaffiliated with any major unions, parties, or other social organizations. Those autonomous organizations generally took the name of Movimiento de Trabajadores Desocupados [Unemployed Workers’ Movement] of their given territory. The MTD of Solano, a locality in the southern part of Buenos Aires’ urban periphery, was one of these. The organization initially emerged from meetings at a local parish and then, after being evicted from the parish by the Bishop, expanded to bring together different neighborhood groups of the unemployed across the territory of Solano, ultimately encompassing hundreds of families. Despite remaining autonomous from political parties and trade unions, they did, at different times, join different political alliances and coordinating bodies, most importantly the Coordinadora de Trabajadores Desocupados Aníbal Verón (Aníbal Verón Unemployed Workers’ Coordination), which brought together many of the different autonomous unemployed workers’ organizations to organize actions together and support one another’s initiatives.

While the workshops focus on the specific experience of the MTD of Solano, the complex cartography of different organizations of the unemployed is referenced throughout the book. Frequent mentions are made of organizations such as the Federación Tierra y Vivienda (Land and Work Federation, FTV, lead by Luis d’Elía) linked to the Central de Trabajadores Argentinos (Argentine Workers’ Central Union, CTA), the Corriente Clasista y Combativa (Class-based and Combative Current, CCC, affiliated with the Revolutionary Communist Party), the Polo Obrero (Workers’ Pole, affiliated with the Workers’ Party) and the Movimiento Teresa Rodríguez (Teresa Rodríguez Movement, MTR). Each of these organizations have their own histories, compositions, practices, and ideological and theoretical positions. It is in that sense that Colectivo Situaciones refers to the unemployed workers’ organizations as a whole as “a movement of movements.” These different organizations and movements would sometimes come together in specific actions or campaigns. Notably a couple of “National Piquetero Congresses” attempted to bring together organizations of the unemployed across this spectrum, however, without much lasting success. As the MTD of Solano recounts here, there were major differences in terms of how to relate to the state and forms of internal organization. For the MTD of Solano, many of these other groups represent ways of doing politics based on a way of thinking based on “globality,” thinking in terms of predefined concepts and understandings of power, rather than starting from the situation. That way of thinking, starting from the situation and insisting on the autonomy to define one’s own concepts and on the self-affirmation of one’s own project, is what sets the MTD of Solano apart from many of these other organizations of the unemployed.

Another major sources of difference and tension among the organizations of the unemployed was their relationship to what in Argentina are colloquially known as “subsidies,” the complex array of welfare benefits packages offered to the poor and the unemployed. These subsidies were one of the primary demands of the movements in the roadblocks and other mobilizations. Eventually, they came to include a wide range of programs offered by different levels of government (from municipalities to the federal government). Originally proposed as individual welfare benefits to the poor and the unemployed, the movements demanded, and won, the right to collectively administer the programs. This meant that organizations would receive the money, distribute it to their members, deciding who was eligible based on their own criteria and, in cases of corresponding work requirements, determine what counted as “work” in order to subsequently receive benefits. Of course, this had mixed consequences. It led to a swelling of the ranks of the organizations of the unemployed, as people signed up in order to have access to those benefits. It also led to accusations of clientelism, of organizations essentially paying people to show up to their events or otherwise using the programs to the sole benefit of leaders. In other cases, it led to interesting experiments in collectivizing the benefits – pooling benefits to use them to use for common projects – and redefining what was considered work – valuing care and community labor above all else.

Of course, the organizations of the unemployed were also part of a broader constellation of movements, organizations, and alternative economic practices during the crisis. These include the neighborhood assemblies of largely middle-class urban neighborhoods and the barter clubs which extended across the country, using alternative currencies and barter to trade for goods and services as the official economy collapsed. As the members of the MTD of Solano explain here, the movements of the unemployed had complicated and evolving relations with these other movements and practices, sometimes coming together across class differences and sometimes entering into irresolvable tension. Yet, as a whole, this complex constellation of movements was responsible for a unique moment of experimentation in terms of forms of life, ways of organizing economic and social relations, and of producing knowledge.

Twenty Years of 2001

A lot has changed in the twenty years since Hipotesis 891 was originally published. Ultimately, much of the energy of the revolt in 2001 was institutionalized, with the election of Nestor Kirchner in 2003 and then of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner in 2007. Their administrations not only increased the subsidies and other benefit packages available to the poor, and specifically to social movements and cooperatives, but also incorporated movement leaders into government positions and created programs directly designed to booster those alternative economic activities that had emerged in the crisis. The conversations with the MTD of Solano included in this book make it clear that there were already intense debates about the issue of institutionalization between different organizations of the unemployed. These tensions only increased Kirchner’s election as many organizations jumped on the opportunity to participate in official policies, while others began defining themselves precisely in opposition to that institutionalization and organized around explicitly fighting against the Kirchner governments, accusing them of co-opting and pacifying movements.

The position of the MTD of Solano can best be described in Raquel Gutierrez’s terms as non-state-centric. In Gutiérrez’s words, a non-state-centric politics “does not propose confrontation with the state as the central issue nor is it guided by building strategies for its ‘occupation’ or ‘takeover;’ but rather, it is strengthened by defense of the common, it displaces the state and capital’s capacity for command and imposition, and it pluralizes and amplifies multiple social capabilities for intervention and decision-making over public matters: it disperses power as it enables the reappropriation of collective decision-making and speech over matters that belong to everyone because they affect us all.”2 In that sense, the MTD of Solano always prioritized its own project: the project of creating new forms of life, new social relations, and new subjectivities in the neighborhoods where they worked. This never meant completely ignoring the realm of the state, and it often meant directly organizing forms of collective self-defense against state repression. Yet, they also continued occasionally receiving subsidies and grants from the state and other institutions, when they determined that doing so would further their organizational needs and not greatly sacrifice their autonomy. Most of members’ energy went into the group’s productive projects, from a bakery to community garden, their neighborhood health clinic, and popular education and pedagogical processes, and to maintaining the alliances and coalitions to support those projects. The MTD of Solano discusses this in terms of not letting their practice be defined by “the political conjuncture.” Instead, the organization’s project and needs, the project of creating new modes of life, were always prioritized over conflicts taking place at the level of state politics, no matter who was in the presidency.

The divisions which became present under Kirchner and Fernandez’s governments, in some sense, only intensified with the election of right-wing neoliberal Mauricio Macri in 2015. Macri represented a return to many of the neoliberal economic policies of the 1990s, but with a friendlier face, that sought to incorporate the popular sectors into the neoliberal project. In this sense, it sought to reestablish a neoliberal subjectivity at the base of society, individualizing welfare benefits and encouraging “entrepreneurship” at all levels of society.3 Macri’s administration was also responsible for taking out the largest IMF loan in the institution’s history, for cutting subsidies for utilities for the middle class, and undercutting unions in wage negotiations. In this context, many movements became further entrapped by the spatialities and temporalities of state politics, focusing their energy on electoral campaigns and influencing politicians in power, rather than the autonomous grassroots experiments that had characterized much of the 2001 uprising.

It was also a moment of new alliances and political strategies. Starting during Fernandez’s government, Colectivo Situaciones and the MTD of Solano focused much of their efforts on constructing new alliances and research initiatives with emerging subjectivities of struggle, particularly migrants, precarious workers, and, later, feminist organizations and collectives. This research also focused on shifts at the level of popular subjectivity – on forms of what some referred to as microfascisms – as increased competition, identitarianism, and authoritarian behavior were being enacted on the extremely local level. One of the clearest examples of this was the case of Parque Indoamericano, in which three thousand families, mostly Bolivian and Paraguayan migrants, occupied the park and set up a temporary encampment, only to be violently attacked by more middle-class neighborhood residents and state forces. Three migrants were killed in the police’s raid on the park, which was yet celebrated by many of the white middle and upper-class sectors of society.4 Members of Colectivo Situaciones and the MTD of Solano worked together with collectives of migrants and other urban researchers in the Hacer Ciudad (Making the City) workshop to investigate changes occurring in the city, and the subjectivities of its inhabitants, at multiple scales. This research, and the web of alliances that carried out it, was thus able to diagnose the Macri government in a novel way, emphasizing those shifts in subjectivity that accompanied a generalized precarization of life.

Living in Freedom: Resonances Today

Twenty years after its original publication, the debates and themes raised in Hipotesis 891 are more relevant than ever. Both the process from which the book emerged – research militancy – and the concepts proposed, such as counter-power, autonomy, horizontality, new forms of militant commitment, and new understandings of freedom, offer important insights for movements today. With this translation, we hope to contribute to the further circulation and dispersion of ideas and concepts, allowing them to travel to new territories, be transformed in the process, and contribute to the mutual contamination of struggles for our collective liberation.5

The first of these themes, and that which has made the name Colectivo Situaciones well-known in the English-speaking world, is that of militant research or research militancy. The concept traveled broadly through different militant translations of Colectivo Situaciones’ work and their participation in movement encounters and events across Europe and North America, entering into dialogue with other concepts ranging from conricerca to participatory-action research. Hipotesis 891 does not offer theories of militant research, but rather demonstrates a process of militant research. As Colectivo Situaciones explains in the prologue, they understand militant research as both a critique of traditional forms of academic research as well as the politics of most leftist movements and non-governmental organizations that is based on already knowing the answers. Instead, the offer a politics that in itself involves research, questioning, and collectively constructing responses. Colectivo Situaciones maintains a commitment to the knowledge produced in struggle and also a commitment to the idea that knowledge can and must be used for struggle. Today, when the term “militant research” is regularly used in academic articles and texts, it is worth returning to the question of the purpose and practice of research militancy. Ultimately, as Hipotesis 891 highlights, research militancy is not primarily about another way of doing research, or least research that assumes academia as its main site of enunciation. Rather, it is about another way of doing politics, that does not follow a predetermined line or presume to know the answers a priori, but that sees research as part of the political process itself.

Another key theme, which highlights the uniqueness of the MTD of Solano’s approach to politics and organizing, is their emphasis on the production of subjectivity. This emphasis highlights the fact that we are not fully formed subjects at the beginning of a political project and that politics takes place, among other levels, on the level of subjectivity. We see this emerge in two different ways in the MTD of Solano’s analysis here. First, it can be seen in their critique of capitalism as producing particular subjectivities and desires, particularly as they see that manifest in their neighborhoods in terms of cut throat competition and lack of solidarity between neighbors. Rather than condemn those neighbors, they seek to understand how those elements are a fundamental part of capitalism’s reproduction and expansion. The second element, involves asking how the movement can function as a space for the production of different subjectivities. Thus they ask what pedagogical practices are necessary, what forms of decision-making and internal discussion are helpful, for creating subjectivities that are not oriented by the logic of capitalism. Again, there is no predefined path for this, but it involves transforming all of those who participate in the project. As members of the MTD of Solano put, “we have also proposed to recreate ourselves, to subject ourselves to change as well, as we have thrown all our certainties out the window.” This also means being willing to engage with comrades who make mistakes, recognizing how we have all internalized elements of the capitalist logic, and that we must be willing to work through that process of transformation together. Thus, instead of searching for the “right” subject to engage in revolutionary activity, whether determined by some sort of identity or class position, the MTD of Solano always understood their task to be that of producing a revolutionary subject.

Finally, the MTD of Solano always stood out, even in Argentina, for its understanding of power – and counter-power – and autonomy, moving beyond a state-centric politics. Counter-power, as posed by the MTD of Solano, is not in symmetrical opposition to power, the power of the state, the power of domination, power over. Rather, counter-power operates differently, on a different realm. Counter-power is the power of creation, the power to act, the power to affect and be affected by others. This commitment to counter-power lies at the heart of the MTD of Solano’s non-state-centric politics, which is not driven by a logic of confrontation with the state nor the desire to take state power. Here autonomy arises as a horizon, not a fixed state but a process through which and toward which the movement works. They attempt to progressively create more autonomy both in terms of the sustainability of their alternative economic projects that allow them to meet some part of their daily needs while relying increasingly less on state subsidies, and in terms of the autonomy of thought and language, proposing their own analyses, their own concepts, for understanding and creating the world in which they want to live. Counter-power ultimately manifests through enacting other ways of living together, ways of organizing work without a boss and managers, ways of living intimate relations beyond the heterosexual nuclear family, ways of cohabiting spaces without hierarchical governments. Or as the MTD proposes, “It is very important to recognize that it is not about transforming the municipal government, or the police force, among other things, but rather that these things exist today as things that we no longer want, we reject them, we negate them. We don’t want to substitute any part of that system, we want to build something different. And it is that new thing that we are envisioning, constructing. That is counter-power.” This is a project that ultimately proposes “a project of living in freedom,” understood as freedom from capitalist imperatives of how to live our lives and the collective creation of new forms of life that allow us to lives and our relations to each other in their fullness.

Thanks to Minor Compositions for allowing the publication of this introduction and the corresponding excerpt from Hypothesis 891. Beyond the Roadblocks.

References

| ↑1 | In the remainder of the text, we use the gender-neutral term piqueterxs, which has been widely taken up in recent years thanks to the mass feminist movement and that highlights the important role that women played in the movement as a whole, although it was often not recognized at the time. We opt to maintain the Spanish term rather than simply refer to “the unemployed,” because, as the MTD of Solano explains later in this book, piqueterx refers to a political identity, an identity based on action and resistance, while “the unemployed” merely refers to a sociological description, which is often depoliticized and cast in the position of a victim. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Raquel Gutiérrez Aguilar, Horizonte Comunitario-Popular. Antagonismo y producción de lo común en América Latina. (Cochabamba: Sociedad Comunitaria de Estudios Estratégicas y Editorial Autodeterminación, 2015), 89. |

| ↑3 | For more on these shifts in subjectivity and the spread of a “neoliberalism from below” during both the late Kirchner period and the Macri’s government, see Verónica Gago’s Neoliberalism from Below: Popular Pragmatics and Baroque Economies (Durham, NC: Duke Press, 2017) and Diego Sztulwark’s La ofensiva sensible: Neoliberalismo, populismo y el reverso de lo político (Buenos Aires: Caja Negra, 2019). |

| ↑4 | For a militant research process analyzing the Parque Indoamericano Case, in which Colectivo Situaciones was involved with migrant collectives, see Taller Hacer Ciudad, Vecinocracia: (Re)tomando la ciudad (Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón and Editorial Retazos, 2011). |

| ↑5 | For more on dispersion and the work of the book, as it travels, in the construction of movements and struggles, see Magalí Rabasa, The Book in Movement: Autonomous Politics and the Lettered City Underground (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019). |

The post Living in Freedom: Notes on Colectivo Situaciones and MTD Solano’s <i>Hypothesis 891</i> appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

05.12.2022 à 19:27

Robert Linhart and the Circuitous Paths of Inquiry

A dossier tracing Robert Linhart's approach and commitment to militant research through new translations of texts spanning the late 1970s to the 2000s.

The post Robert Linhart and the Circuitous Paths of Inquiry appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

Texte intégral (940 mots)

Introduction to Robert Linhart: Concrete Analyses in the Spider’s Web of Production | Paul Rekret, Eoin O’Cearnaigh, and Patrick King

Consistent with his rejection of a romanticization of the working class, Linhart insists that workers’ knowledge is fragmented and partial, if also profound. The task of the inquiry is, thus, to collect via dialogue and participation, this disjointed state of collective memory and oral testimony in support of a systematic understanding of the whole.

Evolution of the Labor Process and Class Struggles (1978) | Robert Linhart

If we want to understand something, I think there’s nothing to do but go see it oneself and to patiently collect the most direct knowledge possible. Go see the sites of production, speak with workers and businesspeople, engineers, work where possible together with workers, participate directly in production. This patient work of identifying reality as concretely as possible is what I call “making inquiries.”

“Technology Transfer” and Its Contradictions: Some Aspects of Algerian Industrialization (1977) | Robert Linhart

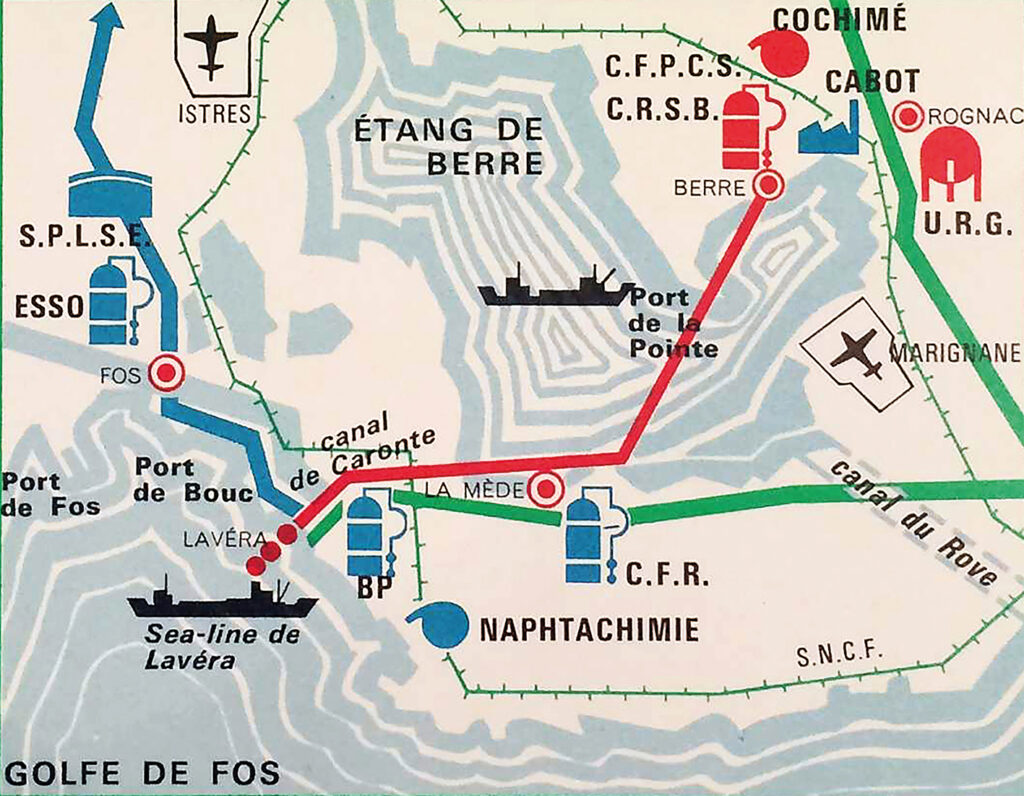

The concrete functioning of those industries which have been “offshored” or set up by “transferred technology” in Third World countries has hardly been studied in a systematic way, and we only have scattered and disparate data on this subject. It is regarding this concrete process that we would like to make a few remarks. The contradictions at work in the process of industrialization in Algeria are far from having produced all their consequences.

The Labor Process and the Division of the Working Class (1978) | Robert Linhart

The development of outside firms permanently employed across the cluster effectively transforms the division of labor in a thoroughgoing manner, more or less insidiously changing the function of workers of the petrochemical enterprise, and in many cases coming to load the position of the working class in this sector with ambiguity – posing a problem (more or less assumed) to industrial and trade union action.

This Concerns Everyone (1981) | Robert Linhart

In all capitalist countries, organizing work means dividing workers: exploring ever new “labor reserves,” just as one begins production on a new mining deposit, wearing down and laminating its dense cores. The organization of labor never stabilizes, even in periods where technology remains constant. Workers resist a mode of exploitation which seeks, limitlessly, to intensify work and make labor-power more lucrative and capitalism strives to detect and deepen weak points within worker resistance.

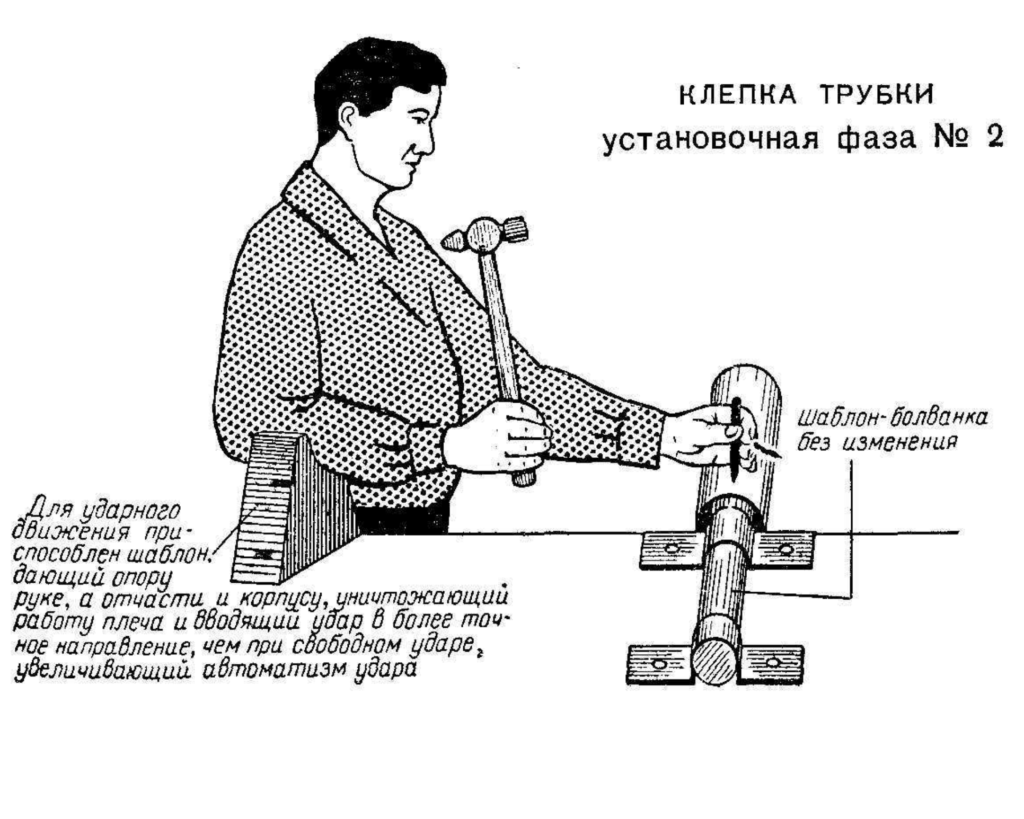

Taylorism Between the Two Wars: Some Problems (1983) | Robert Linhart

In the concrete organization of labor existing in the field, we encounter a combination of different modes of workplace organization developed up to the present moment, a combination that is the result of employer policies, working-class practices and resistance, economic factors external to the internal organization of the labor process, and various elements of the class struggle in society. It is critical, then, to not be limited to a mode of workplace organization that, at each given moment, occupies the forefront of the ideological scene, but to take into account the totality of the real organization of labor, to the extent that one can grasp it or reconstruct it.

Evolution of the Organization of Labor (1998) | Danièle Linhart and Robert Linhart

In the present context, what we are seeing does not really resemble the establishment of innovative organizations breaking with the Taylorist logic, but much more a mixture of genres where innovations are introduced but within a logic that remains fundamentally Taylorist. Management is engaged in a constant project to seek out another mode of control, domination, and coercion of employees before preparing the passage toward possible reforms of the organization of labor which could be rendered more compatible with the demands for responsiveness imposed by the market and new forms of competition.

The Time-Sick Hospital (2005) | Robert Linhart

In these very difficult workplace situations, all the agents interviewed indeed stressed the importance of the group. The existence of a genuinely solidaristic and very active work group functions as a shock absorber for those temporal tensions and multiple dilemmas that are the daily lot of full-time staff on the razor’s edge.

The post Robert Linhart and the Circuitous Paths of Inquiry appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

05.12.2022 à 19:27

Taylorism Between the Two Wars: Some Problems (1983)

In the concrete organization of labor existing in the field, we encounter a combination of different modes of workplace organization developed up to the present moment, a combination that is the result of employer policies, working-class practices and resistance, economic factors external to the internal organization of the labor process, and various elements of the class struggle in society. It is critical, then, to not be limited to a mode of workplace organization that, at each given moment, occupies the forefront of the ideological scene, but to take into account the totality of the real organization of labor, to the extent that one can grasp it or reconstruct it.

The post Taylorism Between the Two Wars: Some Problems (1983) appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

Texte intégral (7618 mots)

The following remarks do not stem from a strictly historical interest in the period under consideration. Rather, they throw a retrospective glance and interrogate some historical issues on the basis of investigations into the organization of labor across different industries. In light of these investigations, carried out in connection with workers and union organizations in automobile, petrochemical, steel, cement, and textile factories, we seek to examine the formation of present systems of industrial labor. How might this specific approach influence the very content of the analysis? It seems to lie in this fact: if we begin with texts and documents from the period in question, which is the most common way to do so in historical research, we are often implicitly led to adopt the dominant viewpoint, that of the capitalists and the organizers of work, quite simply because this viewpoint has left behind the most extensive written traces, is presented as a coherent system, articulated as such. An entire reality, experienced by the working class (a reality made up of the resistance to the capitalist organization of labor, of the mismatch between theoretical organization and actually implemented organization, and the parts of the productive system left in the dark by the official representations of industrial labor) has remained in the collective memory and oral tradition, without finding a systematic form that could act as a counterbalance to the organizers of work. If we adopt the viewpoint of the investigation among the agents of the production process, and the workers in the first instance, we find a grasp on the effective operation of the system of workplace organization, and not only on the always idealized and rationalized presentation provided by the organizers of capitalist production: we follow a contradictory concrete application, we discover the limits, failures, the whole complexity of relations of forces in motion.

For this reason, before passing on to the analysis of texts from the interwar period, it is useful to offer a few general observations drawn from recent investigations in industrial facilities, which might help us in a critical reading of documents that mainly come to us from the organizers of the capitalist labor process.

Some General Observations

First, the systems of workplace organization in capitalist industry do not succeed one another pure and simple: they are superimposed onto each other, as it were, the older systems surviving by combining with the new ones. One fairly often finds, in presentations of the capitalist organization of labor over the past century, a tendency to simplify its periodization into large homogeneous periods: pre-Taylor, Taylor and scientific management, human relations, job enrichment, autonomous groups, etc. But while it is true that we can perceive the succession of relatively distinct periods from the perspective of the “overall ideological tonality” concerning the organization of labor, on the other hand everything indicates that in the concrete organization of labor existing in the field, we encounter a combination of different modes of workplace organization developed up to the present moment, a combination that is the result of employer policies, working-class practices and resistance, economic factors external to the internal organization of the labor process, and various elements of the class struggle in society. It is critical, then, to not be limited to a mode of workplace organization that, at each given moment, occupies the forefront of the ideological scene, but to take into account the totality of the real organization of labor, to the extent that one can grasp it or reconstruct it.

So, in the present period, sometimes a bit too quickly described as post-Taylorist, Taylorist standardization is in the process of taking root in certain sectors of industrial production (cleaning, maintenance in particular – the industrial cleaning sector, which is currently undergoing a phase of Taylorization in France, employs about 20,000 workers). In office and tertiary sector work, computerization has triggered a wave of Taylorist normalization that is now underway.

In industries generally known for mainly implementing mechanisms of workplace organization which depend on a rather broad autonomy of groups of workers, some sectors remain very Taylorized: packing and shipping in the petrochemical and chemical industries, quarrying in the cement industries, for example.

We can go even further and argue that in general, the abandonment of the assembly line in favor of the various systems of “modules” or “job enrichment” in some parts of production in no way undermine, even in these parts, from the basic Taylorist principles: normalization of gestures and tools, strict time standards, the prior decomposition and preparation of work and tasks.

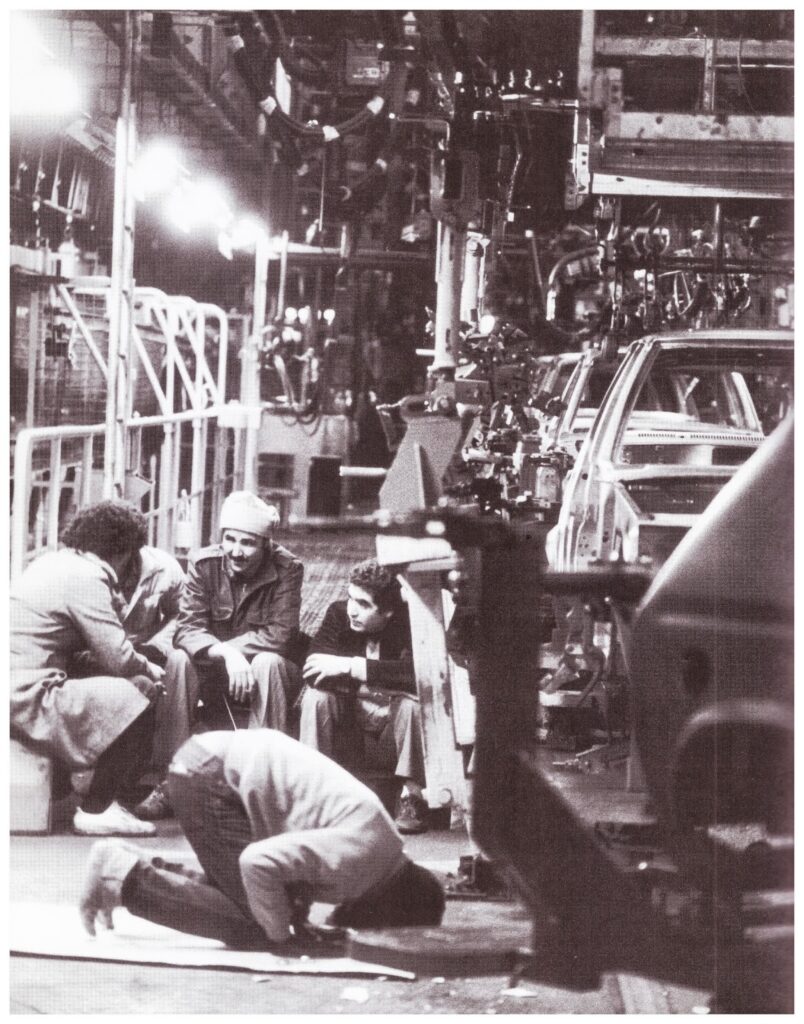

Inversely, in industries that represented the advanced point of the Taylor system, some sectors have resisted complete absorption up to the present day. For example, in the auto industry, the maintenance sector (machine tools, electrical) have retained a resiliency and relative independence in the organization of tasks and time, which gives skilled workers a status that could be described as privileged in relation to semi-skilled [OS] workers (at least this is still primarily the case in the French auto industry, but signs of challenge to this autonomy are beginning to appear). At times, even the Taylorized sectors have burst open, which has created very heterogeneous situations: the same automobile firm that developed robots on the assembly line (soldering, painting, etc.) may also use so many seemingly archaic methods as the contracting-out to very small workshops or even domestic work for certain pieces.

It is above all imperative to be careful of the optical illusion which pushes the most “modern” system of workplace organization to the foreground in the eyes of the employers and thousands of engineers, when it still only possesses a limited reach. In the lead-up to World War I, the Taylor system became the object of fierce debates. But, in that epoch, Taylorization in the strict sense only applied to a few tens of thousands of workers in the United States itself.1

We are witnessing today, whether in “job enrichment” or “autonomous work groups,” a comparable ideological bloat of the ideological presentation in relation to the real development.

The real development proceeds in a much more conflictual and contradictory manner than the idealized version of a linear development of the organization of labor as science lets on. This is what we want to attempt – briefly – to highlight in the interwar period which concerns us.

Analysis of Interwar Texts

In 1927, the International Labour Office published, in Geneva, a report titled Scientific Management in Europe. Its author, Paul Devinat, who headed the ILO’s relations with employers’ organizations, had established close relationships with American industrial circles and obtained financing from the Twentieth Century Fund to conduct a study on the state of Scientific Management in different European countries, in order to generalize the “new methods.” This report is highly interesting for several reasons:

– First of all, as an ideological case study. It indeed reflects the kind of “rationalizing” fever which took hold over manufacturing leadership circles in those years between 1925-1929, 1927 representing perhaps a high point. Taylorism is presented by Devinat as not only as an instrument of organization internal to firms, but as an overall view of economic life – we would be tempted to say a worldview.

– Next, it gives some interesting indications (although they are to be taken with reservations, due to its propagandistic aspect, particularly toward the workers’ movement) on the attitude of different social forces participating in industrial production vis-a-vis scientific management. The vanguard role of engineers and technicians, as a social milieu, is clearly emphasized.(Recent studies confirm the role of engineers in the ideological advance of Taylorism. See, for France, the article by Aimée Moutet, “Les origines du système du Taylor en France: Le point de vue patronal (1907-1914),” Le Mouvement social 93 (October-December 1975): 15-49. For the United States, see the article by Alessandra Lorini, “Il passaggio del principio di efficienza dallo Scientific Management alle scienze sociali negli Stati Uniti (1890-1920), Testi e Contesti 1 (May 1979).))

– Lastly, it makes a clear assessment of the institutional situation of scientific management in various countries in Europe, including the Soviet Union, and indicates what he sees as the existing differences among them in the application of scientific management.

If we analyze this balance sheet by relating it to the concrete situation of the epoch, we discern in Taylorism’s development not only the mere extension of the method invented by Frederick Winslow Taylor, but a complex process marked by the class struggle, through which the organization of labor takes form from crisis to crisis.

– Taylor’s works were explicitly aimed at a general conception of class peace: “scientific” laws ruling over labor, its intensity, its remuneration, imposed on both bosses and workers, the transition to mass production opening at the same time an era of universal prosperity. The ideological struggle Taylor waged in the United States, the high point of which was his 1912 testimony before the Special Committee of the House of Representatives, led him to put an even sharper emphasis on this presentation.

But the beginnings of the introduction of the Taylor system in Europe around 1910 appeared first as the narrow application of its most obviously coercive aspects, like timekeeping. This brutal introduction would give rise to fierce resistance from workers, especially the Renault strikes in 1912 and 1913. Throughout 1913 there were lively polemics in France around Taylorism.2

Also in 1913, on the other side of Europe, Lenin published his first, harshly critical, article on the Taylor system in Pravda: “A ‘Scientific’ System of Sweating,” following a conference on Taylorism at the Railway Engineering Institute in St. Petersburg. We witness in Europe too, right before the outbreak of World War I, an initial diffusion of the Taylor system, accompanied as it were by a fairly severe ideological “opening round” between workers and socialist and trade union milieus, on the one hand, and those introducing the system (capitalists or engineers) on the other.

We know how the war, due to ideological mobilization, internal repression, and abrupt transplantations of producing populations (male workers to the front, women to the factory, etc.) enabled a breaking of these resistances in several sectors, particularly those most tied to wartime production (arsenals, munitions and gunpowder factories, armored vehicles, etc.).

After the war and the great wave of workers’ struggles which immediately followed it, the problem raised its head anew. Business and government circles and the engineers at the forefront in the diffusion of scientific management drew lessons from the “opening round”: an entire ideological offensive now surrounded the uptake of the system, even if it meant adapting certain aspects, or combining it with other practices. You might say that at that time period, there was a transition from the introduction of schemes [recettes] to a deliberate drive toward “Americanization” writ large.

This evolution is very clear-cut in the preface to Devinat’s report, written by Albert Thomas, a former Socialist minister of armament in the French Sacred Union government during WWI, who became president of the International Labor Office. In this text we find a critical tone toward the brutal Taylorization of the initial years, and also read a desire to go about it better in the future:

If the writer of these few lines may be allowed to give his personal reminiscences, he would recall the initial attempts made in France during the years 1907-1908 to introduce time-study methods and Taylorism—attempts which were accompanied by errors and abuses, by an excessive imitation of American systems and inadequate preparation, by a violent commotion in the minds of the working classes, and by the whole struggle against what was called “systematised sweating.” […]

Later, during the war, it became essential in France to devise methods to ensure the fullest possible utilisation of the depleted staffs of the factories engaged in war work, and this led French factories to introduce, in many cases for the first time, methods of mechanical transport, to make the first attempt at “chain work”, and even, in certain powder mills, to undertake regular motion studies of women workers with a view to increasing output and reducing fatigue.

An entirely new factor, however, and one that goes back only a few years, is the realisation by American business men of the enormous power which the systematic and rational practice of the new methods has given them. Intuition has told them that these are the methods required, not merely to reintroduce intimacy in the relations between workers and employers and to imbue industry with a fresh spirit of development, but also to reconstruct the older European society disorganised by the war, or, in a word, to promote the happiness and advancement of civilisation.3

What arguments does this ideological offensive concretely depend upon? With workers as the main resistance, we easily detect an overarching operation to try to surmount and circumvent the trade union organizations. Themes of worker protest: scientific management drains workers, scientific management leads to a rise in unemployment. Focus areas for the propaganda of the “new methods”: scientific management lessens fatigue, scientific management improves the overall functioning of the economy and makes it possible to reduce unemployment over the long term.

These two focus areas of propaganda combined with research and practical initiatives which gave form to the Taylorism of the interwar period;

– a reorientation toward psychology and psychotechnics [psychotechnique]: Taylorism must be supported by a better understanding of man at work;

– a firm economistic interpretation: Taylorism must launch a “rationalization” of the whole economy.

Evolution of the Psychological Content of Scientific Management

A new theme strongly emerges in Europe in the 1920s: scientific management reduces fatigue. Whence the importance accorded to everything having to do with the “psychological” and “psychotechnical” aspects of the study of labor in the ILO report. It is lamented that France remains an exception to the general tendency toward a “closer association between industrial psychology and industrial technique.”4 On the other hand, Weimar Germany is cited as a leading country in this domain: “Germany has made enormous progress in psycho-technology,” and that the applications of industrial concentration and standardization undoubtedly “pay more attention to the human factor than elsewhere.”5 Great Britain is included too. According to the examples provided, German “psychotechnics” seems more focused on vocational selection and “scientific employment,” the British application on fatigue.

While at several points the report cites psychophysiology as one of the elements of scientific management capable of making it more acceptable to workers, it also resorts to psychology to support, in the broadest sense, the new order ushered in by Taylorism:

To-day the man at the head of any undertaking must be primarily an organiser, a man that is to say who has been carefully trained for his work, not merely by technical education in particular subjects, but by a general instruction in economics and sociology and by a serious study of applied psychology, which last forms in fact the basis of the science of organisation, its real subject matter rightly understood being the functions in regard to production of all who are engaged in industry, from the worker to the manager. Its essential object is to secure the best possible contribution from each individual by putting him in his right place and securing universal harmony and collaboration.6

This is followed by praising of scientific management that guides all the elements of production to collaboration, and which “is the enemy just as much of routine and red tape as of irresponsibility and speculation.”7 Everyone in their place, in a natural order, from the supervisors to the manual operators: how can one not think of the themes of fascism (the equally physiological or “biological” claim), and more broadly, how can one not feel the simmering of an entire “social technology” which takes off in the first half of the 20th century? Is it by chance, for that matter, that the report further on, while describing the scientific management propaganda in different Europe countries, indicates that

Institutions also exist in a number of countries for the sole or main object of securing publicity. The most typical institution from this point of view would appear to be the Italian national committee ENIOS established under the auspices of the Italian General Confederation of Industry—a powerful body owing its existence to the initiative of the employers.8

The tightly-linked combination in the interwar period of Taylorism with a certain “psychology’ in order to confront workers’ resistance is in our eyes the nodal point of a series of fundamental questions: the movement in the methods of the capitalist organization of labor can be grasped. The ILO report is particularly explicit in this regard:

The close connection between Taylorism and industrial psychophysiology was not at first realised; indeed, it frequently happened that the latter science supplied arguments against the introduction of Taylorism in the workshop…It is thus clear [today] that the two movements were destined to become complementary to each other so soon as the leaders of the scientific management movement, under pressure of social considerations and of the necessity for winning the support of the organised workers, provided adequate guarantees against abuses.9

And further:

The definitive orientation of the scientific management movement in Europe appears to date from the coalescence of Taylorism and industrial psycho-physiology, of which the foundations were laid during this phase. The physiologists, who hitherto had specialised to an excessive extent…began to realise that the application of Taylor’s principles provided a means of turning the results of their studies to immediate use. On the other hand, the followers of Taylor were enabled to appeal to the results of experiments carried out for some time past in Europe in support of their advocacy of a system of overseas origin.

The effect of the agreement which thus came into being on the opinion of the workers was particularly fortunate.10 Once the physiologists abandoned their attitude of hostility to Taylor’s principles and realised the fundamental identity in the methods and object which both schools were pursuing, the workers automatically acquired a guarantee against the abuses.…Thus, in England, where the strength of the labour movement is considerable, scientific management methods were introduced to public opinion and defended before it by the industrial psychologists[.]11

It must be stressed that we see the implementation here of a system of pressure on labor-power, and in our present, we can inquire about the at times ambiguous roles played by ergonomics, occupational medicine, psychology, etc. Do not employer policies often combine the direct strengthening of exploitation and the intensification of labor with an array of operations [manipulations] that are dubbed “humane,” handled by specialists who, in principle, do not organize production?

Does this psychological tendency correspond with a reorientation of Taylorism? Does it only develop some of the basic principles of Taylorism? Or does it rather constitute a crisis and important transformation of the Taylor system? A complicated question, which we simply want to aid in posing, not resolving.

In the first place, the Taylor system presents itself from the start as an extremely tight grid around the producing population within the factory, accompanied by a much more intimate and systematic knowledge of each individual, each gesture, by the management than in the past. This control can be described as the bureaucratization of the labor process, which necessarily leads to the ideal situation that Taylor presented before the Special House Committee in 1912:

The fourth of the principles of scientific management is perhaps the most difficult of all of the four principles of scientific management for the average man to understand. It consists of an almost equal division of the actual work of the establishment between the workmen, on the one hand, and the management, on the other hand…In a machine shop, again, under this new type of management there is hardly a single act or piece of work done by any workman in the shop which is not preceded and followed by some act on the part of one of the men in the management. All day long every workman’s acts are dovetailed in between corresponding acts of the management. First, the workman does something, and then a man on the management’s side does something; then the man on the management’s side does something, and then the workman does something; and under this intimate, close, personal cooperation between the two sides it becomes practically impossible to have a serious quarrel.12

A tight grid, but narrowly delimited in its object: it involves dividing the tasks of production between design functions and implementation functions. Everything takes place inside the labor process, and a distinct function of management over men has not yet emerged. Here is the first form of Taylorism, the first version of Taylorist control: Taylor imagined he could reduce workers to a mere physical capacity, by concentrating mental activity on the side of management. There is the famous retort calling for workers not to think, the comparison of pig-iron handlers with a trained gorilla, in short all the remarkable contempt for workers that oozes from the founder of scientific management’s body of work and which his successors were precisely unable to maintain in the face of the initial resistance from the workers’ movement.

More profoundly, Taylor’s resolutely individualist hypothesis is upended by the reality of the class struggle in the factories during the interwar period. It is known that Taylor outright refused to treat workers as a group. One of his basic principles is that there must be a direct relationship between the management of the firm and each worker, with the mediation of unions or even work teams. We thus read in Scientific Management:

As another illustration of the value of a scientific study of the motives which influence workmen in their daily work, the loss of ambition and initiative will be cited, which takes place in workmen when they are herded into gangs instead of being treated as separate individuals. A careful analysis had demonstrated the fact that when workmen are herded together in gangs, each man in the gang becomes far less efficient than when his personal ambition is stimulated[.]13

This is in fact what Taylor calls a “psychological” analysis; and it is this strictly individualist psychological approach that is in crisis between the two world wars. The end of the 1920s and the 1930s are marked by the famous experiments conducted by Elton Mayo and his team (General Electric, etc.) that emphasized group effects, and opened the way to psychosociological practices (“human relations”) which continue to play a very important role in employer strategies of workplace management. Taylor’s whole hyper-rationalized conception of human behavior will subsequently be challenged, to the benefit of other forms of ideological offensive and, after World War II, theories and practices stemming from psychoanalysis.14

In any event, workers’ resistance to the introduction of Taylorism caused employers to mobilize “psychology” and the “human sciences,” which played an important role. The ILO’s report tends to present this new stage in an idealist fashion as the rapprochement of disciplines. It is not hard to read between the lines here to see a system of alliance of capital with many strata of the petty bourgeoisie. While the direct organizers of production (engineers, supervisors, monitors, timekeepers, etc.) played a key role in the initial phase of the implantation of Taylorism, new professions were rallied: doctors, psychologists, sociologists, etc. A second, more peripheral wave of bureaucratization of labor process came to superimpose itself upon the first. And, in a broader manner, the battle over production, which had become sharper at the level of society as a whole, was brought to the political level: the theme of the “third way,” reformist currents, fascism, preparation of the New Deal, etc.15

Toward the Crisis of the Taylorist Economy

Although in 1927, at the moment of the ILO’s report, the “psychological” narrow-mindedness of pure Taylorism was already outpaced by methods of the organization of labor, in contrast Taylorist economism was in full swing, even its peak. Two years later, the crisis will deal it a direct blow. And, before the Second World War broke out, the economic postulates of the first version of Taylorism will be seriously questioned, as its psychological postulates had been several years prior. The 1927 ILO report arrived between these two shocks that shook scientific management. It was still imbued with the idea that the generalization of Taylorism to the economy considered as a whole could only be a positive development: scientific management strengthens the system of production and allows for the growth of consumption; at the cost of temporary unemployment, it assured more stable employment for the future (one already recognizes here the persistent and widely used theme of capitalist governments’ austerity campaigns; it is difficult to disentangle in this language pure propaganda and system of belief: it is a whole overarching representation that is is formed in the management circles of the capitalist economy, which does not rule out the concealment of certain unforeseeable effects of the system for the purpose of public opinion).

The 1927 report rests upon “purist” Taylorist positions, since this generalizing viewpoint can already be found in Taylor, albeit more at the level of general principles than concrete applications. Two examples are noted at length in the report: the overall rationalization in resource allocation and inter-industry organization in Germany; product standardization and the fight against waste in the United States. Two names: Rathenau, Hoover. It is striking to see all the hopes that a figure like Hoover still embodies in 1927, who would a few years later become essentially the symbol of the disastrous policy which worsened the 1929 crash.

In the report’s appendix, there is an extract from an ILO memorandum on scientific management, presented to the “Preparatory Committee of the Economic Conference,” which is a fine rendition of scientism:

Scientific management is the science which studies the relations between the different factors in production […] Scientific management owes its existence as a separate science to the work of Frederick W. Taylor…Since his day scientific management has considerably evolved…From the time of Taylor to that of Hoover great progress has been made in America…Already there is in certain countries a tendency to call scientific management by the more appropriate name of rational organisation of production[.]16

Germany’s example follows. And further:

Another item in the scientific management programme, namely, the systematic elimination of waste, has, since the publication of Mr. Hoover’s celebrated report [Waste in Industry] in the United States, become a matter of general public interest. The utility from the national point of view of the elimination of waste is no longer disputed, and its partisans are already urging that the campaign should be carried into the international field.17

A simple idea: why not apply methods of standardization, selection, and compartmentalization that seemed to be so successful for the Taylorist reorganizers of determinate production facilities to the economy as a whole? This all fits into a strict Taylorist logic. But, the same was the case for “psychological” problems, with a kind of reductive narrow-mindedness. The entire economy becomes a massive firm to “Taylorize.” According to this perspective, there is a continuity and homology between the microeconomic and the macroeconomic: what is good for one firm is good for the totality of firms. In 1927, this was still believed among the leading circles of the capitalist economy. But after 1929? Was not the crisis precisely the weakness of this logic?

Keynesian thought and the new practices of economic management that stemmed from it appeared as a break with the basic principles of the Taylorist economy and their systematization by Hoover. The micro could not be extrapolated from the macroeconomic: these are two systems obeying two different laws, sometimes even opposing laws. The economic policies and restrictions which drew on the Taylorization of workshops led to catastrophic results. At the level of the overall economy, it is imperative to know about spending, spillover. What could be more absurd, from a strictly orthodox Taylorist perspective, than those hypotheses which Keynes jokingly asserted: that in certain cases, it is useful to employ people to dig holes so that others could fill them up? These new principles, however, would influence the anti-crisis policies of the 1930s.

It is thus another strand of the Taylorist system of references that was buried with the great crisis, the New Deal, Keynesian theories. The very extension of the Taylor system burst open its contradictions.18 For there to be high wages, there must be low ones, and for there to be favorable yields, there must be other, unfavorable ones; if it is no longer so, it will be equalization from the bottom. Already in 1918, in a polemic with Bukharin, Lenin argued that the absolute monopolization of the capitalist economy is impossible: monopolies need smaller firms and basic forms of competition to preserve their differential rents.

There is a whole debate to be had on this question of the crisis of initial Taylorism and its later trajectory. Several texts have recently appeared in France presenting Keynesianism as the logical development of Taylorism, everything culminating in a complete apparatus that would unify the control of production and consumption, for which the term “Fordist mode of production” has been proposed. It seems to me that this linear perspective on the organization of labor in the 20th century does not take into account the scope of the crises mentioned above, and underestimates the transformations that class struggles in the enterprises and societal contradictions have caused in the effective organization of labor.

The organization of labor is precisely the result of these struggles and these contradictions, not the mere expression of a “science which would grow through its own laws.” Scientific management does not escape this feature, whatever the scientific pretensions it wraps itself in.

– Translated by Patrick King

This text first appeared in Travail et emploi 18 (1983): 9-15.

This article is part of a dossier entitled “Robert Linhart and the Circuitous Paths of Inquiry.”

References

| ↑1 | Lenin cited the figure of 60,000, drawn from American sources; see also the text by Aldo Lanza, scholar at the University of Turin, “Taylorismo, fordismo e movimento di riorganizzazione industriale negli USA, 1890–1920,” Testi e contesti: Quaderni di scienze storia e società 2 (1979): 93-114, building on the work of Daniel Nelson. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Émile Pouget, L’organisation du surmenage: le système Taylor (Paris : Rivière, 1914). |

| ↑3 | Paul Devinat, Scientific Management in Europe, vi-vii. |

| ↑4 | Devinat, Scientific Management in Europe, 78. |

| ↑5 | Devinat, Scientific Management in Europe, 43. |

| ↑6 | Devinat, Scientific Management in Europe, 43. |

| ↑7 | Devinat, Scientific Management in Europe, 45. |

| ↑8 | Devinat, Scientific Management in Europe, 62. Translator’s Note: The French version has propagande for “publicity.” |

| ↑9 | Devinat, Scientific Management in Europe, 25-26. |

| ↑10 | TN: The French has “au point de vue ouvrier” for “opinion of the workers.” |

| ↑11 | Devinat, Scientific Management in Europe, 34-35. |

| ↑12 | Frederick Winslow Taylor, “Taylor’s Testimony Before the Special House Committee,” in Scientific Management (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1974 [1947]), 44-45. |

| ↑13 | Frederick Winslow Taylor, Principles of Scientific Management (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1913), 73. |

| ↑14 | See Frederick Herzberg, Work and the Nature of Man (London: Staples Press, 1968). |

| ↑15 | For an analysis of the internal contradictions of the pure Taylorist strategy (if every worker becomes the “best worker” in the Taylorist sense, the differential advantages of the system cancel themselves out: general implementation is impossible and crisis situations emerge with the extension of the system) and the birth of different strategies, we refer to the useful article by Andrew Friedman, “Responsible Autonomy Versus Direct Control Over the Labour Process,” Capital & Class 1, no. 1 (Spring, 1977): 43-57, esp. 50-52. |

| ↑16 | Devinat, Scientific Management in Europe, 169-70. |

| ↑17 | Devinat, Scientific Management in Europe, 40. |

| ↑18 | See on this subject the argument on the absurdity of generalizing the Taylor system to the entire economy in Friedman, “Responsible Autonomy Versus Direct Control Over the Labour Process.” |

The post Taylorism Between the Two Wars: Some Problems (1983) appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

05.12.2022 à 19:27

Evolution of the Labor Process and Class Struggles (1978)

If we want to understand something, I think there’s nothing to do but go see it oneself and to patiently collect the most direct knowledge possible. Go see the sites of production, speak with workers and businesspeople, engineers, work where possible together with workers, participate directly in production. This patient work of identifying reality as concretely as possible is what I call “making inquiries.”

The post Evolution of the Labor Process and Class Struggles (1978) appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

Texte intégral (12267 mots)

Critique communiste: Robert Linhart, you led the Althusserian tendency within the Union of Communist Students (UEC), which went on to establish the Union of Communist Youth (Marxist-Leninist) (UJCML).1 In May 1968 we often clashed with the UJCML under your leadership. After your organization’s crisis and that of the Maoist current more generally, you didn’t follow the same path as a good number of former Maoist leaders recast today within the intellectual establishment of the academy and the “Nouvelle Philosophie.” When anti-Leninism was at the peak of fashion, you published a book that was incongruous with this trend: Lenin, the Peasants, Taylor.2 You’ve just published The Assembly Line with Minuit, a personal account we all read and appreciated at Critique Communiste.3 With hindsight, what is your assessment of your militant past? How do you understand your militancy now?

Robert Linhart: The critical moment in the collapse of so-called “Maoist” organizations can be situated around 1972. In any case, throughout their decade-long existence, from their birth inside UEC onwards, our successive organizations always existed in a state of crisis. Independently of all the external upheavals and contradictory pressures emanating from wider society, they contained an element of internal crisis: our attempt to break with a mode of action conceived solely as a form of primitive accumulation of a capital of militants. We seized upon the Chinese Cultural Revolution for forms of organization that were more contradictory and unstable than those previously bequeathed by the tradition of the communist movement. As Marxist-Leninists, we sought radical innovation in terms of the theory and practice of organization. We sought to establish a much more dialectical type of organization, one capable of calling itself into question, of destroying itself, of shifting itself from one social base to another, of recomposing itself. Against the orientation of our own “Marxist-Leninist” and then “Maoist” organizations, we launched “movements” that by their repetition and magnitude contributed to surprising growth and breakthroughs, and also provoked perpetual crises. The final crisis intervened between 1971 and 1973.

Certainly, other organizations born since have claimed Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought for themselves. But it seems to me that the overall situation in which they conduct their efforts and the relationship that they can have with the Chinese Revolution today are very different than those existing for previous waves. I will only speak, therefore, of the generation of Marxist-Leninist militants in which I participated, myself.

At the time of that final crisis, the problem we confronted, insofar as we were professional revolutionaries – passing from a single strike to the organization of a group of factory militants, from a movement among the armed forces to a prison uprising, from organizing a demonstration to writing magazine articles – can be easily formulated: how to reinsert ourselves back into society? No doubt, like me, you know the tremendous consequences of individuals operating enclosed within a politically confined world, where we only know people who share our own views, and where all information is passed through an incredibly rigid grid. A collective interpretation is almost always immediately arrived at and the world, deprived of its mysteries and of its complex hues, ends up reduced to a collection of stereotypes. We see schizophrenic behavior begin to develop. A dream-world and a dream-France, only distantly related to the real world and the real France, are constructed. The mechanics of this breakdown are easy to unpack. For a few hundred people between 1965 and 1972, France was only perceived through strikes, demonstrations, incidents that broke out at different points in society or in the state apparatus. These people never engaged in ordinary activity in a business, an office, an ordinary community, as we do every day (including the uneventful days!). The cross-section of society that we knew had no value for a representation of the whole, since we always chose places where things were happening. Elsewhere things were quite spectacularly not happening; an essential part of reality escaped from view, and a completely distorted view of reality resulted.

This always posed a problem and it took a particularly acute form in the end. When I worked for the press of the GP (Gauche prolétarienne) (J’Accuse and then la Cause du peuple-J’Accuse), two lines were vigorously opposed to each other. One sought to establish a relationship with reality that was not entirely disconnected – nor deceptive: if only 500 people attended a demonstration one would say that there were only 500 people; if a strike went badly, one would explain why it went badly. The other line could be called voluntarism or idealism but it also encompassed those forms that were most skeptical towards the will to power and careerism of petit-bourgeois intellectuals. This line consisted in saying: we represent the proletariat; if our comrades from the rank-and-file demand that we say that there were 10,000 people then we must say so, etc. Conflict of this sort occurred regularly and pushed us into a vicious cycle: voluntarist pressures cut us off from those we called “democrats” or people we could have formed links with, and this greatly reduced our ability to appreciate reality.

There’s one point I’d like to insist upon. I describe here what I knew directly. But, in my opinion, it’s a very general phenomenon. While certain so-called “Maoist” organizations took this capacity for schizophrenia to an extreme, it seems to me to be a property of all far-left organizations. No doubt, for other comrades it’s not actually exhibited in such a pathological form, but it is evident from reading their newspapers, or from listening to their interpretations of events, that the whole of social reality finds itself sifted through a very weak framework, with very few variations and where one can almost always predict in advance what will be said of one thing or another. By the way, this is what always makes reading the far left’s newspapers an absolute source of sadness. Moreover, far-left militants often see themselves as somehow sticking to reality by accepting the institutional form through which our society produces “news” (items reported or even constructed by the major newspapers and other journalistic outlets and indeed “political life” itself, as is seen these days with “anniversaries” and other such idiocies…). In bowing down before this artificial superstructure, they more often than not neglect to explore fields of reality that almost never appear on the news (since the news is a rigorously limited representation that society generates of itself). At the extreme, there is a curious conjunction of schizophrenia and conformism, which I believe would make a good subject for analysis. This mechanism, which we came to know in pathological form, continues to exist in a mode that could be described as more routine, more normal…

These problems about how to perceive the world and how to reinsert ourselves back into society have confronted us for a long time, including the whole period of our activity as professional revolutionaries. One can always evade the issue, until the moment comes when the organization collapses and everyone finds themselves at sea. Whether or not we want to, each of us then has to re-enter “ordinary” relations with society. Or, not quite always, to tell the truth. It’s a question of occupational and social activity as well as of one’s mentality. And, certain well-placed individuals find a loophole at a price – affordable enough to them apparently – of becoming spectacular turncoats. Fundamentally, the leading rhetoricians and other windbags of the nouvelle philosophie continue to follow the same old formula. They turn out any old sophistry from scraps of reality, which are then sorted through a rudimentary framework before being incorporated into an elaborate fantasy with delirious themes all of its own. This is quite artificial (since they are far from mad…). But only a handful of people who are full of hot air make a lot of noise. The overwhelming majority of militants have been scattered in numerous different directions.

From 1972 onwards, the strategies of people who had participated in our movement came to be abruptly individualized yet again. Everyone tried to find a way out, and there were lots of different routes. Some showed a panic-stricken fear of ordinary life, of the reality of finding stable work again, of having occupational responsibilities. They found for themselves a thousand and one reasons to continue the lifestyle of the militant free from the constraints of common social life, yet still tied to the cultural or intellectual order – all to avoid plunging into the fate faced by the majority of 53 million French people.

Others invested the abilities they had been able to acquire during their militant period in various sectors: campaigning, advertising, research, journalism, psychoanalysis, etc.

Others, for their part, have tried, despite brutal changes in conditions, to maintain continuity in their activity. To both find an occupation, a normal relationship with society, re-establishing a dialogue with people who think and live differently from themselves, while still continuing to fight in this altered universe for the same things: the birth of political forces linked to the working class; resistance to capitalist and imperialist oppression; the struggle against exploitation. Some became lawyers and continued to defend workers by specializing in employment law. Others were linked to the unions. Others even stayed on the shop floor and were said, therefore, to have become “naturalized” workers.

We have covered a very difficult period and I think it has been useful to let the dust settle. The ambitious ones who had bet, 10 or 15 years ago, on rapid revolutionary success to secure their place in the sun did not resist the backlash of the 1970s. Their renunciations multiplied as they threw themselves into the arms of the bourgeoisie. Good riddance. The others, the vast majority, I’m sure, will one day struggle once again, only with stronger convictions and vaster experience.

For my part, I took up the role of teacher and economist. I dedicated all of my work, inquiry, writing, research, teaching, to the question of production. That is to say, essentially, to everything that concerns the operation of industrial and agricultural production, to how goods are produced today: steel, petrol, automobiles, radio sets, knitwear, corn, Liège lace, hormone-laced veal, plates, etc., etc.

Underlying these choices, there is a simple idea. It seems to me that we have a very superficial and hazy understanding of the working class and production. More than a century after Capital, there remains a largely unexplored world to be discovered.

And often we hold on to ideas, definitions, and descriptions from that moment when Marxism was born and first encountered the working-class movement. Well, the world has changed since Marx’s epoch. And if it is true, as Marx said, that the relations of production are the heart of society, of the system of exploitation, it seems to me that it is difficult to form an opinion no matter the subject (ideology, the state, superstructure, international relations, the general tendencies of societies…) without researching relatively concrete (and up to date) knowledge of relations of production – of the real way men produce objects.