05.12.2022 à 19:26

The Evolution of the Organization of Labor (1998)

In the present context, what we are seeing does not really resemble the establishment of innovative organizations breaking with the Taylorist logic, but much more a mixture of genres where innovations are introduced but within a logic that remains fundamentally Taylorist. Management is engaged in a constant project to seek out another mode of control, domination, and coercion of employees before preparing the passage toward possible reforms of the organization of labor which could be rendered more compatible with the demands for responsiveness imposed by the market and new forms of competition.

The post The Evolution of the Organization of Labor (1998) appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

Texte intégral (4944 mots)

Work has changed, especially in the industrial world, where Taylorism established its credentials. With the spread of information technologies, material contact is less and less frequent for many workers, even if it has not disappeared everywhere. Tasks increasingly correspond to oversight, the monitoring of automated systems, control, the management of information and risk.

Organizational competitiveness tied to the new realities of the market and competition also exercises a determinate influence. The conditions of productivity have changed and condition another type of mobilization of employee engagement and the organization of firms: “The new forms of performance all depend on the density and relevance of the relations established between actors and the productive chains, between the functions of the firm (research office, marketing department, commercial services, production), between firms, the suppliers, and their clients, between firms and their social and technical environment.”1

The Post-Taylorist Thesis and the Emergence of New Figures of Labor

From these widely held views, some authors deduce a radical transformation of the organization of labor and even the end of Taylorism, to the benefit of the potential autonomy of workers. A current of thought has thereby taken shape, which discloses the emergence of new functions, new actors, in other words new professional identities, new arenas and new training on the basis of the significance accorded to communication, cooperation, and expertise, as well as engagement and initiative.2

The analysis of these developments is placed at the center of labor sociology, as a new factor in the workplace, and new determinant of organizational choices and competencies.

The quality of cooperation now takes primacy, information becomes the dominant feature. Workers’ skills rests with communication. It is not so much the autonomy of movements, the regularity of labor and its conformity to procedures, to the requisite prescriptions and codes which are required, but much rather a capacity to adapt to exceptional situations, an expertise which enables an appropriate treatment of the “events” which punctuate the labor-process: Reacting to events is now becoming a key component of collective or industrial labor. Qualifications are being displaced by expertise, the analysis of specific situations… One does not only communicate between tasks; the task itself consists in communicating.”3

We are far from the individual work postulated by Taylor: “The community of networked workers is in charge of its own capacity to recompose a collective knowledge,” namely, to work together, to create spaces of reciprocal understanding.4 We are far, too, from the Taylorist worker hyperspecialized in one compartmentalized task to which they are restricted. Jean-Louis Laville defines the new professional figure that has emerged in the following terms: “Office technicians, operators in automated facilities in the manufacturing industry, monitoring operators in the process industries all share the need to situate themselves in an informational series in order to locate and circulate information on which productivity and work quality will depend. Work is increasingly referring back to the culture of workers’ involvement in a universe in motion.” This culture revolves around “autonomy, initiative, the overall perception of the procedure.”5

For the team of Sainsaulieu, Francfort, Osty, and Uhalde, “the world of firms is becoming a real social milieu, where multiple ways of being are expressed in relation to the demands of initiatives and communication, responsibilities, outcomes, creativity that cover the changing life, technical complexity, and relational involvement of work.”6

These sentences from Christian Thuderoz find resonance:

Production, organization, institution: at these three levels of analysis of the firm, change is notable. Different elements are indeed combined in the workshops to sketch a new social and productive state of affairs: other ways of cooperating and self-organizing to produce, appeals to the initiative and responsibility of employees, encouragement of speech, experience in the management of flows, quality control, etc. The hypothesis of new models of organization in North America and Europe seems appropriate. The operators of automated machines and systems now react to contingencies and handle them, analyze sequences, anticipate breakdowns. Whence the importance accorded to communication between individuals, to mutual understanding.7

Moreover, this overlaps with the definition offered by Benjamin Coriat of the super-worker, at the entrepreneurial and managerial helm.8 By definition, these new workers are no longer enmeshed in the logic of prescribing means. Only the objectives remain prescribed for operators at the intersection of several specialities, tasked with a larger range of missions and engaged in multifunctional work groups where the notions of collective work, autonomy, and initiative take on their full meaning.

A Need for Caution

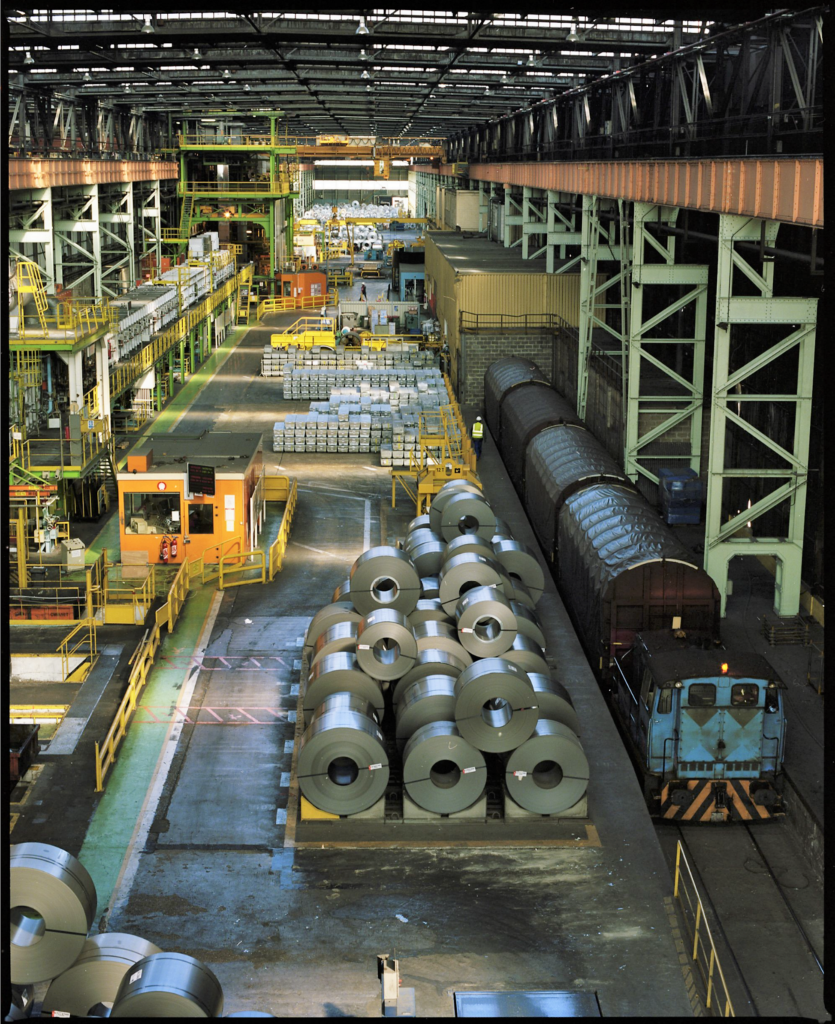

We can note two observations in regard to these arguments asserting a break with the principles of Taylorism in the emergence of new forms of the organization of labor. The first is that the majority of these authors have been influenced by investigations carried out mainly in the process industries, that is, a specific type of manufacturing (among them: cement production, petrochemicals, nuclear sector, steel). In these industries, organizational innovations have indeed been uncovered, notably in the sense of a real multifunctionality involving, for example, worker-technicians who participate in the improvement and optimization of production.

There have always been doubts, however, as to the very presence of actual Taylorism in these industries, considering the division of workstations is problematic given the nature of continuous work. Furthermore, these are industries where labor costs are insignificant compared to capital costs and where questions of reliability and security are paramount, imposing concessions on worker professionalism. For the proponents of post-Taylorism, there is no doubt however that series production industries are beginning to acquire some important characteristics of continuous work, namely increasingly significant investments in information and automation as well as a greater fluidity of the production process with the decrease in inventory, and that they will necessarily adopt their post-Taylorist model. Zarifian states matters in abundantly clear terms: “It is not steelmaking that we want to present as a model, but through it the demonstration of the contemporary characteristics of the evolution of the cooperative dimension of labor.”9

As for the authors who draw on observations carried out in industries of series production or in services, they evince a strong tendency to generalize on the basis of limited cases, in this instance the emergence of new functions, particularly interfaces which require more specialized communication competencies, and thus a professional know-how marked by autonomy and initiative. And moreover, was not the process of deskilling for a majority of workers within Taylorist rationalization always accompanied by the overqualification of small professional groups?

The second observation we might make is that these analyses define more of an “ideal type” than a reality, and curiously abstract from a whole fundamental part of social reality. In this optic, everything happens as if a given type of market constraint and a given type of technical tools necessarily determine a given type of work organization and a given form of employee engagement. As if Taylorism, inter alia, necessarily corresponded to a now superseded specific economic and technological conjuncture. As if, back then, there were no other possible choices.

This overlooks the fact that the forms of the organization of labor are social constructs, that is, they constitute a kind of response to the relation of forces between different actors involved in the situation, relations of forces that they effectively illustrate.

The Multiple Stakes of the Organization of Labor

Taylor never hid that the mode of organization he devised was a means of restraining the workers of the time. The scientific organization of labor thus corresponded to the institutionalization of a certain mode of compulsion, of coercion in the process of labor itself, to an organizational detour that forced workers to work not according to their own interests, but according to what Taylor presented as the good for the greatest number, the good of the nation. We know that this became above all a war machine against the workers.

In the present context, what we are seeing does not really resemble the establishment of innovative organizations breaking with the Taylorist logic, but much more a mixture of genres where innovations are introduced but within a logic that remains fundamentally Taylorist. Management is engaged in a constant project to seek out another mode of control, domination, and coercion of employees before preparing the passage toward possible reforms of the organization of labor which could be rendered more compatible with the demands for responsiveness imposed by the market and new forms of competition.

The authors who sustain the post-Taylorist current of thought all discuss a new type of labor that profoundly involves workers’ subjectivities, their resourcefulness, their communicational capacity without ever raising the question of workers’ acceptance of cooperation, of open and voluntary collaboration with management and with hierarchies. Is it definitely the case that workers, who not long ago were engaged in an ideology of class struggle (during the “Trente Glorieuses”), that is, in an open conflict declaring the non-convergence of interests between workers and bosses, today accept engaging their subjectivity in the service of the enterprise? Certain elements might lobby in favor of this hypothesis: the decline in trade unionism as well as an exceptionally high and stubborn unemployment rate. But its success does not, for all that, seem guaranteed. At least, this is the conviction that modernized management has. As proof you can point to the tremendous effort undertaken by management to “work” the subjectivity of employees, to transform an identity that appears to them still too rooted in the values of the past.

We have, for over ten years now, elaborated the idea of a paradoxical consensus to describe the dominant attitude among workers during the prior period of strong growth.10 A paradoxical consensus, because workers’ very distance in relation to the dominant rationality of the firm, their dissenting attitude prompts them to develop professional behaviors which objectively serve the interests of the firm while contesting its legitimacy, its hierarchical order, the distributions of statuses and powers that it establishes to the detriment of workers, who receive the bare bones; they have developed a whole stock [capital] of knowledge, expertise, know-how, that they clandestinely apply, in other words by resisting commands, prescriptions, hierarchical orders. In the framework of a resistant, recalcitrant, and rebellious subjectivity, they have adopted a more effective and better-adapted attitude than what was required of them by scientific management. And this is because of the reference to the profession, to the job well done, to the shared values of workers which found their collective identity, because of a will to impose, in a world of coercion and subordination, their own vision of economic rationality.11 These behaviors constitute what Jean-Daniel Reynaud calls autonomous regulation, as opposed to the regulation of control coming from management. The effective functioning of labor in firms brings results, in equilibrium according to this theory, in a complementarity between these two kinds of control, which brings about a “joint regulation.”12

Now, what is expected of these employees is consenting cooperation on the subjective plane: here there is an important shift [revirement] whose significance has not escaped managers. The challenge would be to pass to a new phase of control and domination of workers.

Contradictions

It is important to emphasize that managers are striving to develop a new type of social control, which is directly exercised on minds, on subjectivity, without actually initiating transformations in the corresponding organization of labor. We find ourselves in a specific moment of history where new forms of discipline precede, at least partially, the evolution of the organization of labor itself, which leads to a whole series of contradictions indicative of contemporary forms of modernization.

Work has of course changed, in connection with new technological tools: new practices are developing such as just-in-time production, flexibility, automatic control, first-level maintenance, the “management” of flows by operators, for instance. Tasks, as mentioned above, increasingly fall under facility oversight, operations, monitoring. But if we closely observe the new forms of labor, we notice that in the majority of cases these operations are subjected to processes of rationalization, standardization, which empties them of all professional skill and turns them into extremely routinized and simplified tasks, in the same way that the activity of oversight itself has been very codified.

The principles which carefully delineate between tasks of conception and organization, on the one hand, and tasks of execution on the other have hardly changed.

That technological development and new forms of competition open onto new possibilities in the organization of labor, that the place occupied by information flows in the labor process encourages the consideration of new modalities of definition and function does not mean, however, that these possibilities are necessarily implemented. We should not lose sight of the social dimension of Taylorism which corresponds, as noted, to an institutionalization of control and coercion in the labor process itself. Directorates for the most part do not appear, for the moment, to have renounced central Taylorist principles of the organization of labor, because they are not convinced they have access to a sufficiently reliable workforce. On the other hand, these directorates have already launched into what might be called a battle of identity to modernize employees’ minds, that is, to make them internalize the values, culture, the standard methods of reasoning in the firm, in the mode of the one best way approach to management, on the basis of the dominant rationality in the firm and excluding any debate, possible discussion, or possible alternative concerning management style.13 It is a matter of forcing workers to eschew professional solidarities, class solidarities, to embrace only the company’s values.

Even if it is done under influence (controlling and disciplining their subjectivity), directorates are consequently seeking to position employees as full-fledged interlocutors in the firm. And it is here that a very problematic discrepancy intervenes, between the effects of this approach of “enveloping” employees, of transforming their subjectivity as well as their symbolic place in the firm, on the one hand, and on the other the reality of their role in the organization of labor where they most often remain confined within Taylorist horizons, limited by still quite standardized prescriptions and definitions of procedures.

The contradictions are of two orders. Symbolic and psychological above all, since employees find themselves caught in conflicting roles (executants and pawns in the context of a very codified and prescribed organization of labor, interlocutors and actors in another time and space of the firm, that of participative groups, individual discussions with management). But very concrete contradictions, too: the prolongation of the logic of personal growth (an alibi discourse which accompanies the battle of identity and the work of subjectivity), within the organization of labor, is reflected in the keyword of accountability [responsabilisation]: each person is deemed accountable at their job post for the quality of the work they provide and the deadlines in which the work is carried out, and no longer have “management on their back” since the chains of command have been considerably streamlined by the same logic. These changes would be welcome in the framework of a post-Taylorism as some sociologists say they see it. But in the majority of cases, operators have to assume the responsibility imposed on them in what is still an extremely codified universe, where decision-making possibilities are very standardized and without help from management. Operators thus feel trapped: they are not capable of influencing the way in which their work is defined and organized, and the higher-ups, nowhere to be found, no longer provide assistance. If problems arise (breakdowns, various dysfunctions), they find themselves blocked, incapable of undertaking their job and responsibilities.14

We can advance the hypothesis that a very real misery [souffrance] is bound up with these kinds of contradictions which maintain employees in a state of permanent unease, in an exacerbated feeling of increased dependence, especially through the incredible possibilities for control offered by information technology.

– Translated by Patrick King and Paul Rekret

This text was first published in Jacques Kergoat, Josiane Boutet, Henri Jacot, and Danièle Linhart (eds.), Le monde du travail (Paris: La Découverte, 1998), 301-309.

This article is part of a dossier entitled “Robert Linhart and the Circuitous Paths of Inquiry.”

References

| ↑1 | Pierre Veltz, Mondialisation, villes et territoires: L’économie d’archipel (Paris: PUF, 2014 [1996]), Chapter 6. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Renaud Sainsaulieu, Florence Osty, Isabelle Francfort, and Marc Uhalde (eds.), Les mondes sociaux de l’entreprise (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1995); Pierre Veltz and Philippe Zarifian, “Vers de nouveaux modèles d’organisation?,” Sociologie du Travail 35, no. 1 (1993): 3-25. |

| ↑3 | Veltz and Zarifian, “Vers de nouveaux modèles d’organisation?.” |

| ↑4 | Philippe Zarifian, “Vers une sociologie de l’organisation industrielle,” Rapport pour l’habilitation à diriger des recherches, Université de Paris X-Nanterre, 1992; Philippe Zarifian, Travail et communication (Paris: PUF, 1996). |

| ↑5 | Jean-Louis Laville, “Participation des salariés et travail productif,” Sociologie du Travail 35, no. 1 (1993): 27-47. |

| ↑6 | Sainsaulieu et al. (eds)., Les mondes sociaux de l’entreprise. |

| ↑7 | Christian Thuderoz, La sociologie des entreprises (Paris: La Découverte, 1997). |

| ↑8 | Benjamin Coriat, L’Atelier et le Robot. Essai sur le fordisme et la production de masse à l’âge de l’électronique (Paris, Christian Bourgois, 1990). |

| ↑9 | Zarifian, “Vers une sociologie de l’organisation industrielle.” |

| ↑10 | Daniele Linhart & Robert Linhart, “Naissance d’un Consensus, la Participation des Travailleurs”, in D. Bachet (ed.), Décider et Agir au Travail (Paris: Cesta, 1985). |

| ↑11 | Robert Linhart, The Assembly Line, trans. Margaret Crosland (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1981). |

| ↑12 | Jean-Daniel Reynaud, Les règles du jeu: action collective et la régulation sociale (Paris: Armand Colin, Paris). |

| ↑13 | Jean-Pierre Durand, “Vers la société du post-travail?,” L’Homme et la société 109 (1993): 117-126; Danièle Linhart, Le Torticolis de l’autruche: l’éternelle modernisation des entreprises françaises, (Paris: Seuil, 1991); Danièle Linhart, La Modernisation des entreprises (Paris: La Découverte, 1994); Yves Clot, Le Travail sans l’homme? Pour une psychologie des milieux de travail et de vie (Paris: La Découverte, 1995). |

| ↑14 | Danièle Linhart and Robert Linhart, “Les ambiguïtés de la modernisation: Le cas du juste-à-temps,” Réseaux 13, no. 69 (1995): 45-69. |

The post The Evolution of the Organization of Labor (1998) appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

05.12.2022 à 19:26

Introduction to Robert Linhart: Concrete Analyses in the Spider’s Web of Production

Consistent with his rejection of a romanticization of the working class, Linhart insists that workers’ knowledge is fragmented and partial, if also profound. The task of the inquiry is, thus, to collect via dialogue and participation, this disjointed state of collective memory and oral testimony in support of a systematic understanding of the whole.

The post Introduction to Robert Linhart: Concrete Analyses in the Spider’s Web of Production appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

Texte intégral (8769 mots)

The French Trotskyist journal Critique Communiste published a special issue in 1978 to mark the anniversary of the events of May and June 1968. It featured a lengthy interview with Robert Linhart, former leader of the Union de la Jeunesse Communiste (marxiste-léniniste) (UJCML), the organization perhaps most closely associated with the archetype of the Maoist student-intellectual, the soixante-huitard. But, in a striking shift of emphasis, rather than contribute to the litany of quixotic autopsies that characterize the period, Linhart instead pivots the discussion towards what he views as most urgent for Marxist theory, especially the need to engage in concrete inquiry into the labor process.

Some context is useful to understand what is at stake in this interview, entitled “The Evolution of the Labor Process and Class Struggles.” Robert Linhart entered the École Normale Supérieure at Rue d’Ulm in Paris (ENS), the peak of the French university system, in 1963. He soon became among the most intimate of Louis Althusser’s “student-disciples.”1 As the decade progressed, he would also become a regular attendee of Charles Bettelheim’s seminars at the École pratique des hautes études on political economy and socialist construction in the Third World.2 He sharpened his Marxist analytical chops as one of the primary editorial forces behind the journal Cahiers marxistes-léninistes, which served as a theoretico-political training ground for the group clustered around Althusser. Turning to Maoism during a summer working for the Algerian Ministry of Agriculture in 1964, in the following year, Linhart’s intervention proved decisive in reasserting orthodoxy over the Union des Étudiants Communistes (UEC).3 During the previous three years, this youth movement had become more open to the broader Marxist left under the direction of an “Italian” revisionist tendency within the French Communist Party (PCF). The “Ulmards” pro-Chinese anti-revisionism eventually led to their own expulsion from the UEC in 1966. This group of around one hundred militants, mainly ENS students, came to form the UJCML with Linhart at the helm, later that year. The UJCML first rose to prominence through the Vietnam Base Committees: these coordinated anti-imperialist organizations, formed in November 1966 and rooted in neighborhoods, schools, and workplaces, popularized the struggle of the North Vietnamese forces and National Liberation Front in the South against the United States, held discussions, published leaflets and bulletins, and engaged in solidarity actions.4 A delegation visit to China in August 1967 profoundly shaped the subsequent trajectory of the UJCML and Linhart personally. The development of a theoretical analysis came to be anchored in “établissement,” a term derived from the French translation of a speech from Mao’s Hundred Flowers campaign for the integration of intellectuals and the masses.5 Less than a year before the eruption of 1968, the group effectively turned its back on student politics to make “inquiries” by taking up work in the factories.6 Linhart himself would only become établi at the Citroën-Choisy factory in the autumn of that year.7

In May 1968, however, “our Great Helmsman Robert,” as one former comrade sardonically called him, remained at the head of the UJCML and when unrest began in the Latin Quarter, he dismissed it as a “social-democratic plot, orchestrated by Trotskyists to usurp the working class’s legitimate leadership of the struggle for the benefit of the petit bourgeoisie,” going so far as to expel his wife from a meeting for advocating in support of the student uprising.8 As such a position became increasingly untenable, Linhart underwent a severe mental health crisis, which saw him hospitalized for an extended period, just as rioting in student neighborhoods gave way to factory occupations. When, in the fallout from the 1968 revolt, the UJCML is proscribed by the state along with other left organizations, Linhart joins Gauche prolétarienne, acting as the editor of J’Accuse, one of its two journals. The practice of établissement would continue through this period, conceived in part as an inquiry in search of the theoretical principles that would triumph given their identity with workers’ aspirations and practices and not merely derived from doctrine, and to cultivate the more radical elements of the French working class.9

While Linhart judges this span of political work harshly in the interview, J’Accuse was a significant left-wing publication. It advanced a militant yet popular journalism that sought to comb the political relays that had continued after May ’68 between intellectuals and working-class strata. Its opening editorial averred that its content would be “oriented toward reality, in other words expressing what the press is silent about or distorts. It is a matter of telling the truth about the violent battles the people put up against those with power in this world, the truth too about the low-level everyday war waged against…work ‘accidents,’ living conditions, HLM-dormitories, the foyers-rackets[.]” The weekly was to be “popular through its methods,” and correspondents were encouraged to “physically connect with the reality of peasant and working-class revolt, to articulate the currents of contestation that are transforming the different layers of French society.”10 The project of sustaining viable organs of counter-information that could transmit the intelligence of ongoing social struggles remains one of the GP’s most enduring legacies and certainly can be felt in Linhart’s later work.

In “Evolution of the Labour Process and Class Struggles” Linhart describes the permanent state of crisis of the GP as a “much more dialectical type of organization,” whose own existence and form was perpetually in question; one that sought to break with activity designed mainly to accumulate political capital for the militant, as he puts it, rather than seek out the conditions for revolution. But Linhart is also critical of the militancy of this period for its truncated focus on the spectacular; a blinkered, even “pathological” view of reality prevailed, he argues.11 This is a worldview which, according to Linhart, has its watershed around 1972, when the GP is dissolved and its members, along with the wider milieu, are faced with a return to “ordinary” life. For his part, Linhart would return to the academy, spending most of his career teaching sociology at Université Paris-VIII-Saint-Denis.

It is partly in light of conceptions of revolutionary struggle developed through the Cultural Revolution and against the backdrop of the decomposition of the French left that in 1976 Linhart publishes perhaps his most important text, Lenin, the Peasants, Taylor, offering a nuanced and account of the Bolsheviks’ shifting analyses and policies vis-à-vis the Russian peasantry and developments in industrial production.12 Among its most fecund arguments is one revolving around Lenin’s adoption of Taylorist scientific management as a means of developing Russia’s productive forces. In conceiving the party as the political agent of the working class, the latter’s objectification by a bureaucratized, Taylorized labor process is justified on the grounds that newly won efficiencies in production would free the popular masses to participate in the direction of the state. The Russian turn to Taylorism, Linhart argues, thus lay the conditions for a rupture between an authoritarian labor process and the democratization of political institutions.13

We can discern in such a claim the echoes of earlier concerns over the separation of intellectuals from workers, and of the division of mental and manual labor more generally, as developed within the UJCML and GP. These are made explicit in Linhart’s discussion of the fear of the peasantry among the Russian revolutionary intelligentsia whose romanticized adoration of the countryside quickly turns to disgust following their bad reception there. This is a characteristic move for the petit-bourgeois intellectual, Linhart notes, a sentiment witnessed among those who entered the factories in the 1960s “with the religious fervor of men for whom absolute truth has been revealed, and after a difficult experience or defeat, abandon their établissement by declaring that the workers are bourgeois, rotten, or fascists.”14

What, then, was Linhart’s own response to Mao’s injunction for the intellectual to “dismount to look among the flowers” or “settle down” among the workers, where a revolutionary situation is absent? In this respect, “Evolution of the Labour Process” unpacks at some length the method of “inquiry.” This is to return to the term deployed by the UJCML but, by the late 1970s, while still conceived as an operation “at trench level”, still établi, in a manner of speaking, but effected through a scholarly work that seeks to understand contemporary transformations to the conditions of labor. The strategies, experiences, and setbacks of établissement allowed could lead into more adequate apprehension of workplace organization and sociabilities.15

Linhart offers a two-fold line of reasoning for the urgency of such a method and unpacking this here serves to begin to offer a sense of how it functions. First, capital operates with an increasingly sophisticated capacity to obscure reality, to restrict or manipulate knowledge of production. Second, production and circulation themselves grow in complexity as outsourcing and subcontracting extend these processes ever more widely and the divisions and differentiations of labor become ever more intricate and stratified. What might appear as a given, discrete factory or enterprise to an outside observer, Linhart suggests, might involve a whole array of small subcontractors operating across an assortment of sites with vastly disparate working conditions and very different operations. Failure to grasp this is to retain a viewpoint anchored in what remain in many respects “craft” sections of the working class within certain sectors – steel working, auto production, cement making… This is a form of ideology, as Linhart sees it, insofar as it excludes from its frame of reference the “spider’s web” of fragmented labor, some “core,” others “subaltern,” that make it up. It is on this basis that knowledge collected from workers is essential in order to gain crucial, systematic knowledge of “the whole” of specific processes of production today. Consistent with his rejection of a romanticization of the working class, Linhart insists that workers’ knowledge is fragmented and partial, if also profound.16 The task of the inquiry is, thus, to collect via dialogue and participation, this disjointed state of collective memory and oral testimony in support of a systematic understanding of the whole.

Linhart’s investigative throughlines combine specific insights from the roughly contemporaneous efforts to develop a practice of workers’ inquiry and “co-research” in Italy, namely the attention to workers’ subjectivities and the “fractures” introduced into class composition through circuits of migration and the variegated enforcement of job hierarchies. Recent scholarship has traced the diffusion of Italian workerism in France, particularly via the publication of translated Quaderni Rossi articles in the 1968 Maspero collection, Luttes ouvrières et capitalisme d’aujourd’hui, as well as the influence the inquiry-form – as fact-finding, interviews, collective tracts, or questionnaires – would have on far-left groups embedded in the social upsurges of the period.17 Linhart’s elaboration of his approach to inquiry in the 1978 interview allows us to see its resonances with that of a figure like Romano Alquati, who stressed the need for close relations between an “outsider” with deep-seated links to “insiders” at a particular worksite. When Alquati went into Olivetti in the early 1960s, he had contacts with workplace militants active in the local branch of the Italian Socialist Party to lend their expertise and assistance. Alquati grounded his inchieste in discussions with workers themselves, drawing out hypotheses and leads that interacted with shop struggles and bringing in broader layers of workers across plants and job classifications.18 The cultivation of close ties with informal work groups around specific knots of firm-specific issues and labor processes raised the collective analysis to a political level. Likewise, Linhart’s careful introduction of the “core/periphery” world-systems problematic to the differentiation of workforces across a production complex also gestures toward the research Ferruccio Gambino and others were conducting in the mid-1970s on how the “mobility of labor-power” and the “mobility of capital” constituted “complementary aspects of the fractionation of labor,” hardening forms of segmentation and closing down openings for working-class organization.19 Finally, Linhart’s insistence that the introduction of new technology into work relations is always a matter of rebalancing the nexus of capitalist power, integration, and workers’ insubordination finds reverberations with Raniero Panzieri’s criticism of distortions around Marxist views on technological development, the division of labor, and workers’ control.20

“Evolution of the Labor Process and Class Struggles” provides a series of examples of how the move from fragments to system might function, although it bears remarking that it does not take up the literary form of an episodic first-person narrative that Linhart otherwise adopts in The Assembly Line, his account of his time établi at Citroën, or Sugar and Hunger, his analysis of the sugar-growing region of Pernambuco in Brazil.21 In the latter, for instance, he offers a rich narrative of his travels through the region as a means of examining the ways an industrialized, sugar-based monoculture wipes out small plots, draws local producers into global markets and class relations. His tapestry of dialogues is expansive, extending to children (themselves often waged workers), a union president, local politicians, engineers, plantation owners; it’s a mode of analysis that operates at different levels of abstraction and, in “settling down” in this way, seeks to avert a reification of Marxist concepts by starting instead from lived experience. This is a means of analysis, in other words, which offers the resources to overcome the apparent contradiction between objective knowledge and a class perspective.22

Not long after “Evolution of the Labour Process and Class Struggles” was published, Linhart largely retreated from public view following a suicide attempt, and with the exception of The Assembly Line, little of his oeuvre has been translated to English.23 It is important to note, however, that Linhart did not completely abandon this commitment to militant inquiry in the later phases of his itinerary, but sustained it through other channels. As he perceptively remarked in a conversation with Charles Bettelheim and the journal Communisme in 1977, there exists a “fantastic disproportion between certain theoretical debates over Marxism and the capacity to understand the concrete class struggle today.”24 Linhart has continued to survey this struggle in its different levels: from international transformations in the process of accumulation, the increasing mobility of capitalist firms and the multiplication of subcontracting, the state’s role in social regulation and labor legislation, different strategic approaches and accommodations from the trade unions, to the strategies of exploitation, spatial division, and resistance that make up the everyday antagonism of the working day.25 He contributed to the lively debates in France at the onset of the 1980s and the arrival of the Mitterrand government into power over the future of the trade-union movement, the destruction of shop floor cultures, and the ideological obfuscations around the Auroux Laws and the devising of new lean production-based “employee participation” schemes.26 He co-wrote reports with other researchers and labor activists involved with the major trade union centers – including his sister, Danièle Linhart, a prolific sociologist of the shifting patterns in the subjectivity of work and managerial techniques centered around the rerouting of autonomy. Through networks and think tanks like the Association d’enquête et de recherche sur l’organisation du travail (AEROT) and the Centre pour la recherche économique et ses applications (CEPREMAP), he made connections with other currents of Marxist analysis of the labor process, recasting the themes and approaches of sociologie du travail in contexts of crisis and restructuring.27 Across all of this activity, he has tackled these scientific analyses of the tendencies of capitalist development, the management and control of labor-power, and workplace organization from the “viewpoint of the working class…among the agents of the production process.”28

In the texts assembled in this collection, Linhart upsets familiar periodizations regarding Fordism and post-Fordism, Taylorism and post-Taylorism, globalization, and other broad characterizations about the changing character of work. He hits upon critical features of contemporary political economy and the labor movement: the redistribution and maintenance of forms of exploitation through outsourcing, arcane legal arrangements of flexible employment, and offshoring in many industries; the interplay of autonomy and subordination in work relations; management surveillance, stress, and knowledge capture in partially automated worksites; and the prospects of worker militancy and union organization among fissured or segmented workforces in larger production and logistics concentrations, across smaller, low-wage shops, and on regional or geographic bases.29 Included are investigations carried out at petrochemical complexes around the Étang de Berre;30 a report on the development of capital-intensive industry and the dilemmas of technology transfer in Algeria, from a visit to the country in the mid-1970s, broaching the the logistical and political questions raised by relations of dependency and underdevelopment in the global value chain;31 historical overviews of Taylorism and consideration of the methodology of the enquête; an inquiry conducted among hospital workers during the transition to the 35-hour workweek in France, tracking the contradictory upshot of computerization and standardization on the labor process in the medical field; and analyses of the structural effects immigration, imperialism, and racialization have had on divisions among the proletariat in France. Linhart has continually highlighted the significance of militants immersing themselves in these situations of investigation and struggle.

This article is part of a dossier entitled “Robert Linhart and the Circuitous Paths of Inquiry.”

References

| ↑1 | Louis Althusser, The Future Lasts a Long Time and The Facts, eds. Olivier Corpet and Yann Moulier Boutang, trans. Richard Veasey (London: Chatto & Windus, 1993), 221. See too Julian Bourg, “The Red Guards of Paris: French Student Maoism of the 1960s,” History of European Ideas 31, no. 4 (2005): 472-490. In an interview with Peter Hallward for the Cahiers d’analyse project which resulted in the Concept and Form volumes (London: Verso, 2012), Etienne Balibar details the seriousness and depth with which Linhart approached the history of Marxist theoretical and political practice from very early on: “Linhart was intoxicated with politics and with Leninism. A little younger than us, he had marked his entrance into our group (the Cercle d’Ulm) in a spectacular way, showing that he knew almost the whole of Lenin’s work by heart. Linhart more or less identified with Lenin. He had read the thirty volumes of his complete works, and memorized them.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | François Denord and Xavier Zunigo, “‘Révolutionnairement vôtre.’ Économie marxiste, militantisme intellectuel et expertise politique chez Charles Bettelheim,” Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales 158, no. 3 (2005): 8-29. |

| ↑3 | Virginie Linhart, Le Jour Ou Mon Père S’est Tu (Paris: Seuil, 2008). For some of Linhart’s writings during this period (including a summing-up of his visit to Algeria), see Robert Linhart, “On the Current Phase of Class Struggle in Algeria,” trans. Peter Korotaev, Cosmonaut Magazine, November 2021; and a 1966 text which originally appeared in Charles Bettelheim’s journal, Études de planification socialiste, “For a Concrete Theory of Transition: The Political Practice of the Bolsheviks in Power,” trans. David Broder, Rethinking Marxism 33, no. 4 (2021): 476-511. |

| ↑4 | See Ludivine Bantigny, “Hors frontières. Quelques expériences d’internationalisme en France, 1966-1968,” Monde(s) 11, no. 1 (2017): 139-160; Kristin Ross, May ‘68 and Its Afterlives (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 90-95; Nicolas Pas, “‘Six Heures pour le Vietnam’: Histoire des Comités Vietnam français 1965-1968,” Revue historique 302, no. 1 (January-March 2000): 157-185. |

| ↑5 | See Mao Zedong, ‘Speech at the Chinese Communist Party’s National Conference on Propaganda Work” (1957), Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, Vol. 5. |

| ↑6 | UJCML, “On Établissement,” (1968), trans. Jason E. Smith, Viewpoint Magazine 3 (2013). |

| ↑7 | Robert Linhart, The Assembly Line, trans. Margaret Crosland (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1981). For a different salting experience in a car factory, see Fabienne Lauret, L’envers de Flins. Une féministe révolutionnaire à l’atelier (Paris: Syllepse, 2018). |

| ↑8 | Jean-Pierre Le Dantec, Les Dangers du Soleil (Paris: Les presses d’aujourd’hui, 1978), 112; Virginie Linhart, Volontaires pour l’Usine: Vies d’Établis (1967-1977) (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2010), 38-9. |

| ↑9 | For an excellent overview in English see Jason E. Smith, “From Établissement to Lip: On the Turns Taken by French Maoism,” Viewpoint Magazine 3 (2013), and Donald Reid, “Etablissement: Working in the Factory to Make Revolution in France,” Radical History Review 88 (Winter 2004): 83-111. For other accounts, see Marnix Dressen, Les établis, la chaîne et le syndicat. Évolution des pratiques, mythes et croyances d’une population d’établis maoïstes 1968-1982 (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2000); the articles collected in the thematic issue of Les Temps Modernes, “Ouvriers volontaires: les années 68, l’«établissement» en usine,” nos. 684-685 (2015); and Laure Fleury, Julie Pagis, and Karel Yon, “‘Au service de la classe ouvrière’: quand les militants s’établissent en usine,” in Olivier Fillieule, Sophie Béroud, Camille Masclet et Isabelle Sommier, with le collectif Sombrero (eds.), Changer le monde, changer sa vie. Enquête sur les militantes et les militants des années 1968 en France (Paris: Actes Sud, 2018), 453-484, 2018. |

| ↑10 | See F.M. Samuelson, Il etait une fois Libé (Paris: Seuil, 1979), 100-101. See too Michael Witt, “On and Under Communication,” in A Companion to Jean-Luc Godard, ed. T. Conley and T. J. Kline (Hoboken-Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014). 318-350, for more on Linhart’s role in J’Accuse and its impact on the filmmaking of Jean Luc-Godard. |

| ↑11 | For an earlier, quite bitter and unforgiving version of this line of criticism contra “gauchisme,” see Linhart’s takedown of Deleuze and Guattari’s 1972 text, Anti-Oedipus: Robert Linhart, “Gauchisme à vendre?,” Libération, December 7, 1974, 12, 9. |

| ↑12 | Robert Linhart, Lénine, les paysans, Taylor (Paris: Seuil, 1976). Rare analyses in English are offered by Dimitris Papafotiou and Panagiotis Sotiris in “Rethinking Transition: Bettelheim and Linhart on the New Economic Policy,” Rethinking Marxism 33, no. 4 (2021): 512-532 and Alberto Toscano, “Seeing Socialism: On the Aesthetics of the Economy, Production and Plan,” in Economy: Art, Production and the Subject in the 21st Century, ed. Angela Dimitrakaki and Kirsten Lloyd (Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press, 2015). |

| ↑13 | Linhart, Lénine, les paysans, Taylor, 91-94. |

| ↑14 | Linhart, Lénine, les paysans, Taylor, 60; it is worth comparing with Linhart’s own work on the Brazilian peasantry in Le Sucre et la Faim. Enquête dans les régions sucrières du Nord-Est brésilien (Paris: Minuit, 1980). |

| ↑15 | In this endeavor Linhart’s work overlaps with that of fellow ex-établi Nicolas Hatzfeld: see his reflection “De l’action à la recherche, l’usine en reconnaissances,” Genèses 77, no. 4 (2009): 152-165; as well as the ethnographic approaches of Michel Pialoux and Stéphane Beaud. See Stéphane Beaud and Michel Pialoux, Retour sur la condition ouvrière. Enquête aux usines Peugeot de Sochaux-Montbéliard (Paris: La Découverte, 2012 [1999]); Michel Pialoux and Christian Corouge, Résister à la chaine. Dialogue entre un ouvrier de Peugeot et un sociologue (Marseille: Agone, 2011); and Michel Pialoux, Le temps d’écouter. Enquêtes sur les métamorphoses de la classe ouvrière, ed. Paul Pasquali (Paris, Raisons d’agir, 2019). |

| ↑16 | See Enes Kezluca, “Theoretical Acupunctures: From Althusser to the Post-Althusserian Marxism of Robert Linhart,” Rethinking Marxism 33, no. 4 (2021): 533-562. |

| ↑17 | See Marcelo Hoffman’s excellent study, Militant Acts: The Role of Investigations in Political Struggles (Albany: SUNY Press, 2016). Hoffman focuses on Dario Lanzardo’s Quaderni rossi article, translated for the Maspero volume as “Marx et l’enquête ouvrière,” in Quaderni Rossi, Luttes ouvrières et capitalisme d’aujourd’hui, trans. Nicole Rouzet (Paris: Maspero, 1968), 109-31. |

| ↑18 | See Romano Alquati, “Organic Composition of Capital and Labor-Power at Olivetti (1961),” trans. Steve Wright, Viewpoint Magazine 3 (2013), and the historical commentary of Steve Wright in Storming Heaving: Class Composition and Struggle in Italian Autonomist Marxism (London: Pluto Press, 2002), 54. Alquati’s methodological notes in Per fare conricerca: Teoria e metodo di una pratica sovversiva (Rome: DeriveApprodi, 2022 [1993]) are also worth revisiting. An excerpt was translated for the indispensable 2019 South Atlantic Quarterly section on militant inquiry, edited by Matteo Polleri. See Romano Alquati, “Co-research and Worker’s Inquiry,” South Atlantic Quarterly 118, no. 2 (April 2019): 470-78. |

| ↑19 | Ferruccio Gambino, “Class Composition and US Direct Investments Abroad,” Zerowork 3 (1974). See too Gambino’s comments on the subject in his interview with Dylan Davis, “The Revolt of Living Labor,” Viewpoint Magazine, November 2019. |

| ↑20 | See Raniero Panzieri, “The Capitalist Use of Machinery: Marx Versus the ‘Objectivists,’ ” trans. Quintin Hoare, in Outlines of a Critique of Technology, ed. Phil Slater (London: Ink Links, 1980), 44-68. |

| ↑21 | Robert Linhart, The Assembly Line and Le Sucre et la Faim. For a helpful commentary on the latter work, see Marcelo Hoffman, “A French Maoist Experience in Brazil. Robert Linhart’s Investigation of Sugarcane Workers in Pernambuco,” Cahiers du GRM 16 (2020). See too Robert Linhart, “Dette, l’ouvrier et le paysan au brésil,” CEPREMAP Working Papers, no. 8903 (1989). |

| ↑22 | On this point see Kezluca, “Theoretical Acupunctures: From Althusser to the Post-Althusserian Marxism of Robert Linhart.” Also see Louis Althusser’s coruscating comments on “concrete analysis” and workers’ inquiry in What is to Be Done?, ed. and trans. G.M. Goshgarian (London: Polity Press, 2020), 1-24. |

| ↑23 | With a few exceptions: see Robert Linhart, “Western ‘Dissidence’ Ideology and the Protection of the Bourgeois Order, trans. Patrick Camiller, Rab-Rab 5 (2019): 273. The text originally appeared in Pouvoir et opposition dans les sociétés postrévolutionnaires, ed. Rossana Rossanda (Paris: Seuil, 1978) and that volume’s English translation in 1979. Other aspects of Linhart’s research program on the figures of labor and modes of production in Eastern Europe can be found in Pascal Bonitzer, François Géré, Robert Linhart, Jean Narboni, and Jacques Rancière, “Table ronde: L’homme de marbre et de celluloïd,” Cahiers du cinéma 298 (March 1979): 16-29. |

| ↑24 | Robert Linhart and Charles Bettelheim, “Sur le marxisme et le léninisme. Débat avec Charles Bettelheim et Robert Linhart,” Communisme 27-28 (March 1977); republished in Revue Période, January 2019. Linhart’s post-Maoist trajectory invites comparison to that of Sylvain Lazarus and the development of a practice of inquiry in the Organisation politique: see Sylvain Lazarus, “Workers’ Anthropology and Factory Inquiry: Inventory and Problematics” (2001), trans. Asad Haider and Patrick King, Viewpoint Magazine, January 2019. |

| ↑25 | See Etienne Balibar, The Philosophy of Marx, trans. Chris Turner (London: Verso, 2007 [1995]), 94-97; and Michel Freyssenet, La division capitaliste du travail (Paris: Savelli, 1977). |

| ↑26 | See Robert Linhart and Danièle Linhart, “Naissance d’un consensus,” CEPREMAP Working Papers, no. 8515 (1985), and Danièle Linhart, “Managerial Innovations: Some Main Tendencies,” AI & Society 8 (1994): 285-291. For an overview of some of these debates, see Jean Lojkine, “The Decomposition and Recomposition of the Working Class, in The French Workers’ Movement: Economic Crisis and Political Change, ed. Mark Kesselman, trans. Edouardo Diaz, Arthur Goldhammer, and Richard Shryock (London: Routledge, 1984), 119-31; the articles gathered in International Journal of Sociology 12, no. 4 (Winter 1982/1983); Alain Lipietz, “Three Crises: The Metamorphoses of Capitalism and the Labour Movement, in Capitalist Development and Crisis Theory: Accumulation, Regulation, and Spatial Restructuring, ed. M. Gottdiener and Nicos Komninos (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1989), 59-95; Beaud and Pialoux, Retour sur la condition ouvrière; and Jean-Pierre Durand and Nicolas Hatzfeld, Living Labour: Life on the Line at Peugeot France, trans. Dafydd Roberts (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003). |

| ↑27 | See Michael Rose, Servants of Post-Industrial Power? Sociologie du Travail in Modern France (London: Macmillan Press, 1979); and the interview with Danièle Linhart in CISG no. 11 (June 2013): 37-54. Linhart’s trenchant criticism of lean manufacturing methods based on quality circles or teamwork concepts dovetails with the indispensable cross-sector and cross-union work done in this area in the US by Labor Notes. |

| ↑28 | See “Taylorism Between the Two Wars” (1983), in this dossier. |

| ↑29 | For further analysis see Danièle Linhart and Robert Linhart, “Les ambiguïtés de la modernisation. Le cas du juste-à-temps,” Réseaux 13, no. 69 (1995): 45-69; Danièle Linhart, Robert Linhart, and Anna Malan, “Syndicats et organisation du travail: un rendez-vous manqué,” Sociologie et sociétés 30, no. 2 (1995): 175–188; Danièle Linhart, Robert Linhart, and Anna Malan, “Syndicats et organisation du travail: un jeu de cache-cache?,” Travail et Emploi no. 80 (September 1999): 109-122. A new text by Robert Linhart was recently published in Crisis and Critique: see Robert Linhart, “Immigration: A Major Issue in Politics Today,” trans. Agon Hamza, Crisis and Critique 9, no. 2 (November 2022): 267-68. It should also be noted that Linhart found this panoramic scope capable of revealing essential tendencies of capital accumulation and labor discipline: “I am always surprised to discover the unity of methods of capitalist management, from the wealthiest centers to the poorest dependent zones. How is the system able to penetrate so far and with such precision?” Linhart, Le Sucre et la Faim, 48. |

| ↑30 | Dominique Pouchin, “L’Éclatement,” Le Monde, March 7, 1980; and compare the contradictions Linhart describes in the petrochemical cluster with those described by the Porto Marghera workers in Italy during a similar time period. It should also be noted that oil and petrochemical refinery workers in France engaged in extended strikes from September to November 2022, causing significant reductions in the country’s overall refining capacity in the context of a broader European energy and cost of living crisis, with the government intervening to break strikes at certain depots. |

| ↑31 | See Linhart’s comments in the introduction to Lénine, les paysans, Taylor, where he observes that a balance sheet of industrialization in the USSR during the 1920s can provide important elements for understanding the relationship between the introduction of new production methods and socialist construction in Third World countries after decolonization and the global economic crisis of the mid-1970s. Linhart, Lénine, les paysans, Taylor, 18. |

The post Introduction to Robert Linhart: Concrete Analyses in the Spider’s Web of Production appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.