Tom Harper, University of East London

China’s already vast infrastructure programme has entered a new phase as building work starts on the Motuo hydropower project.

The dam will consist of five cascade hydropower stations arranged from upstream to downstream and, once completed, will be the world’s largest source of hydroelectric power. It will be four times larger than China’s previous signature hydropower project, the Three Gorges Dam, which spans the Yangtse river in central China.

The Chinese premier, Li Qiang, has described the proposed mega dam as the “project of the century”. In several ways, Li’s description is apt. The vast scale of the project is a reflection of China’s geopolitical status and ambitions.

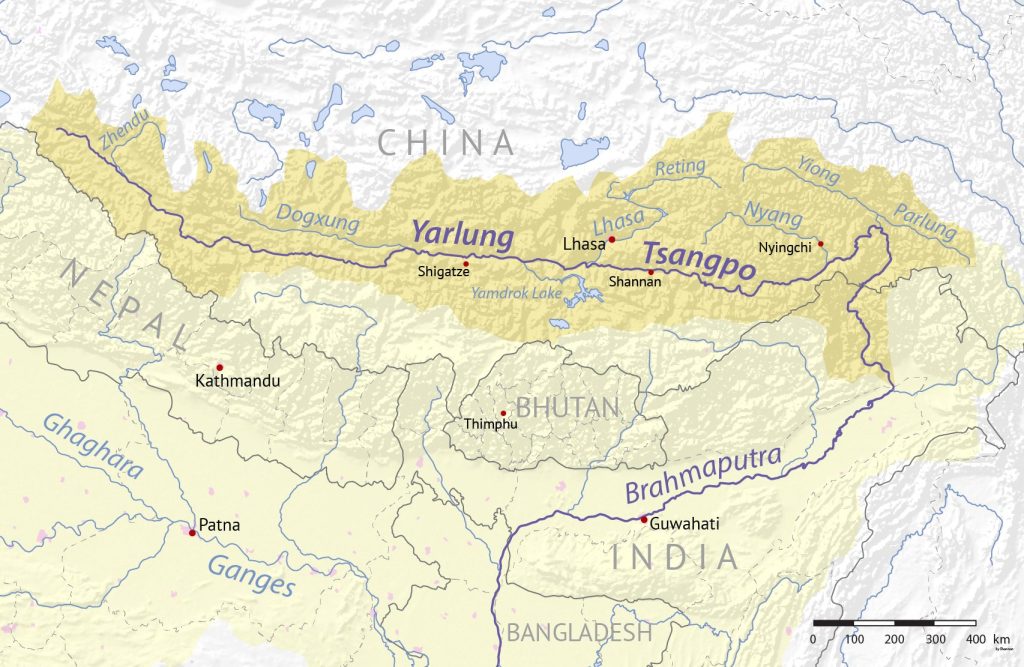

Possibly the most controversial aspect of the dam is its location. The site is on the lower reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo river on the eastern rim of the Tibetan plateau. This is connected to the Brahmaputra river which flows into the Indian border state of Arunachal Pradesh as well as Bangladesh. It is an important source of water for Bangladesh and India.

Both nations have voiced concerns over the dam, particularly since it can potentially affect their water supplies. The tension with India over the dam is compounded by the fact that Arunachal Pradesh has been a focal point of Sino-Indian tensions. China claims the region, which it refers to as Zangnan, saying it is part of what it calls South Tibet.

At the same time, the dam presents Beijing with a potentially formidable geopolitical tool in its dealings with the Indian government. The location of the dam means that it is possible for Beijing to restrict India’s water supply.

This potential to control downstream water supply to another country has been demonstrated by the effects that earlier dam projects in the region have had on the nations of the Mekong river delta in 2019. As a result, this gives Beijing a significant degree of leverage over its neighbours.

One country restricting water supply to put pressure on another is by no means unprecedented. In fact in April 2025, following a terror attack by Pakistan-based The Resistance Front in Kashmir, which killed 26 people (mainly tourists), India suspended the Indus waters treaty, restricting water supplies to Pakistani farmers in the region. So the potential for China’s dam to disrupt water flows will further compound the already tense geopolitics of southern Asia.

Background layer attributed to DEMIS Mapserver, map created by Shannon1, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Concrete titans

The Motuo mega dam is an advertisement of China’s prowess when it comes to large-scale infrastructure projects. China’s expertise with massive infrastructure projects is a big part of modern Chinese diplomacy through its massive belt and road initiative.

This involves joint ventures with many developing nations to build large-scale infrastructure, such as ports, rail systems and the like. It has caused much consternation in Washington and Brussels, which view these initiatives as a wider effort to build Chinese influence at their expense.

The completion of the dam will will bring Beijing significant symbolic capital as a demonstration of China’s power and prosperity – an integral feature of the image of China that Beijing is very keen to promote. It can also be seen as a manifestation of both China’s aspiration and its longstanding fears.

Harnessing the rivers

The Motuo hydropower project also represents the latest chapter of China’s long battle for control of its rivers, a key story in the development of Chinese civilisation.

Rivers such as the Yangtze have been at the heart of the prosperity of several Chinese dynasties (the Yangtse is still a major economic driver in modern China) and has devastated others. The massive Yangtse flood of 1441 threatened the stability of the Ming dynasty, while an estimated 2 million people died when the river flooded in 1931.

Such struggles have been embodied in Chinese mythology in the form of the Gun-Yu myth. This tells the story of the way floods displaced the population of ancient China, probably based on an actual flooding at Jishi Gorge on the Yellow River in what is now Qinghai province in 1920BC.

This has led to the common motif of rivers needing human control to abate natural disaster, a theme present in much classical Chinese culture and poetry.

The pursuit of controlling China’s rivers has also been one of the primary influences on the formation of the Chinese state, as characterised by the concept of zhishui 治水 (controlling the rivers). Efforts to control the Yangtze have shaped the centralised system of governance that has characterised China throughout its history. In this sense, the Motuo hydropower project represents the latest chapter in China’s quest to harness the power of its rivers.

Such a quest remains imperative for China and its importance has been further underlined by the challenges of climate change, which has seen natural resources such as water becoming increasingly limited. The Ganges river has already been identified as one of the world’s water scarcity hotspots.

As well as sustaining China’s population, the hydropower provided by the dam is another part of China’s wider push towards self-sufficiency. It’s estimated that the dam could generate 300 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity every year – about the same about produced by the whole UK. While this will meet the needs of the local population, it also further entrenches China’s ability to produce cheap electricity – something that has enabled China to become and remain a manufacturing superpower.

Construction has only just begun, but Motuo hydropower project has already become a microcosm of China’s wider push towards development. It’s also a gamechanger in the geopolitics of Asia, giving China the potential to exert greater control in shaping the region’s water supplies. This in turn will give it greater power to shape the geopolitics of the region.

At the same time, it is also the latest chapter of China’s longstanding quest to harness its waterways, which now has regional implications beyond anything China’s previous dynasties could imagine.![]()

Tom Harper, Lecturer in International Relations, University of East London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.