The UN Tax Convention could be a game-changer. So why is ambition still stuck in first gear?

Clara Thompson

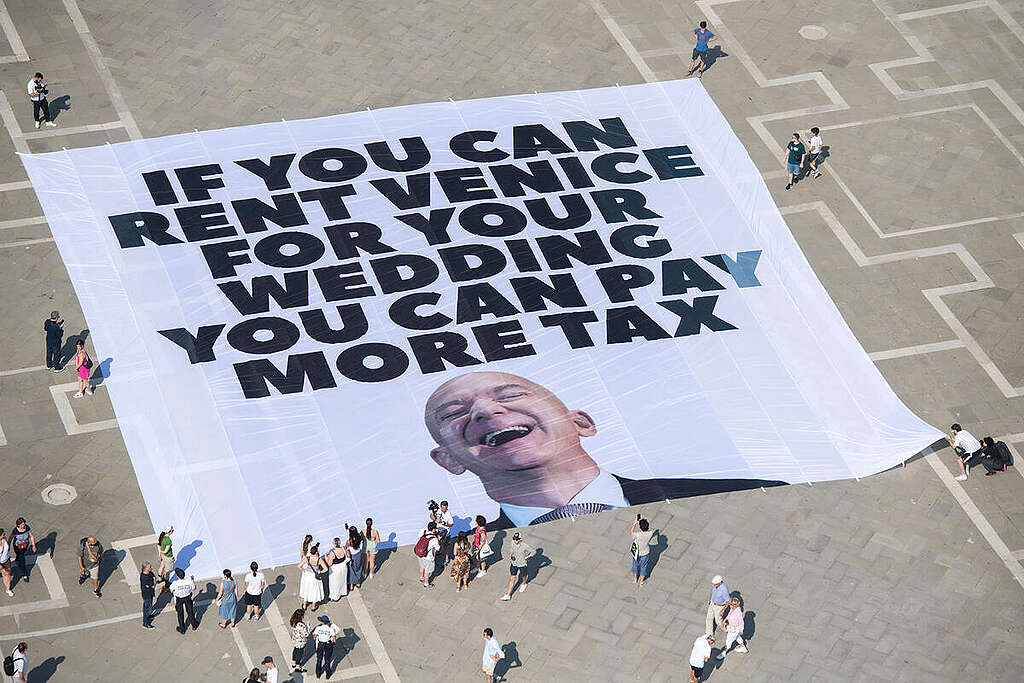

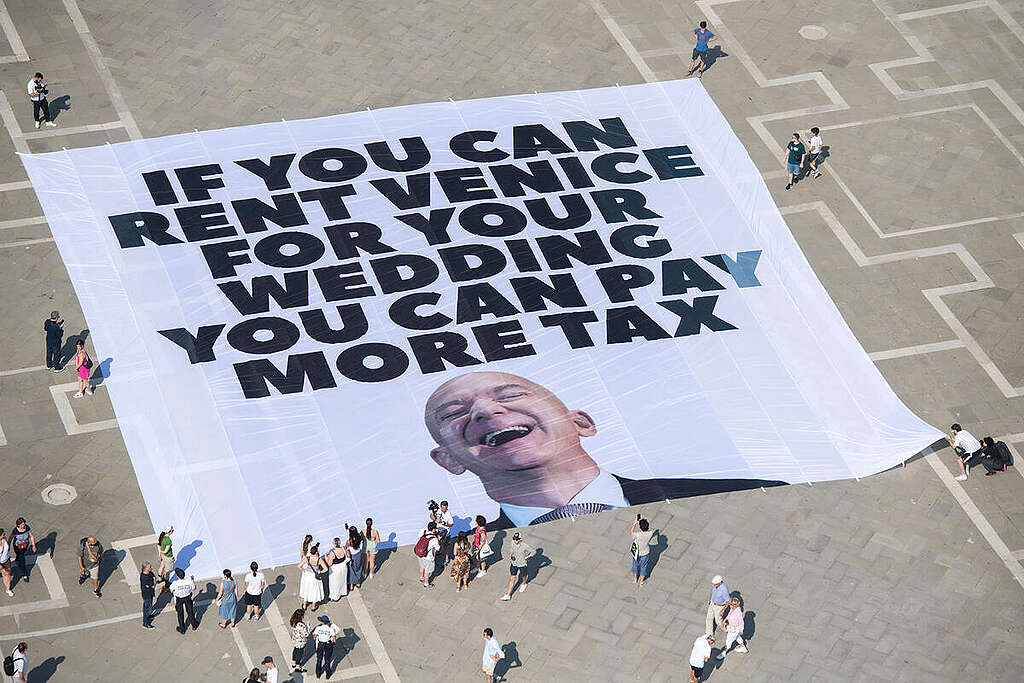

If you’ve been following global climate and finance politics lately, you’ll have noticed a strange contradiction. On the one hand, governments keep telling us we need more climate finance, fairer taxation, and new public resources to deal with climate breakdown, inequality and crumbling public services. On the other hand, when it comes to the one global forum designed to actually fix international tax rules – the UN Tax Convention – that bold ambition doesn’t translate. These negotiations, currently underway in New York, present a unique chance to hold corporate tax avoiders and polluters accountable, unlocking trillions in public funds for climate action, nature protection, and vital public services. Instead of rising to that moment, however, the process risks failing to deliver the transformative change many countries are calling for. Same governments. Same problems. Very different energy. So what’s going on? The latest draft of the UN Tax Convention includes articles on sustainable development and taxing high-net-worth individuals (HNWI). That’s good news. A few years ago, neither would even have made it into the room. But here’s the catch: they’re still written mostly as ‘principles’, not commitments. The sustainable development article remains declaratory. It acknowledges that tax cooperation should support social, economic and environmental goals, without spelling out how, or what kinds of mechanisms would be needed to deliver them. No change to this article since the Terms of Reference were set out. The article on high-net-worth individuals has improved on paper (it uses ‘shall’ instead of ‘agree’ now), but still stops short of what’s actually needed to tax extreme wealth effectively and fairly. In short: governments agree that something should happen, but appear reluctant when it comes to the details of how to actually make it happen. That’s like agreeing to catch smugglers, but banning customs from opening the luggage. This is where things get awkward. In other international forums (COP30, G20, FfD4 to name a few examples), many of the same governments are already making much bolder statements. For example: In 2025, at the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4) in Seville, Spain, governments committed to improving tax cooperation and transparency, explicitly referencing progressive taxation to fund social protection and integrate undeclared wealth, and in written submissions, countries such as Brazil, Colombia, Germany, France, Spain and Sierra Leone have explicitly supported stronger cooperation on HNWI taxation in the UN process. Many African countries, including Zambia and Nigeria, have repeatedly highlighted in their plenary interventions how our broken global tax system undermines development and climate action. Since the UN Tax Convention negotiations began in 2025, at least 17 countries have made supportive statements for more detail to be added on the issue of sustainable development, several of whom have explicitly endorsed inclusion of environmental taxation and the polluter pays principle. And yet, when negotiations move from statements to drafting, ambition narrows. Not all elements raised in countries’ submissions find their way into the Chair’s text, and several governments continue to defer to high-level, non-committal language. Political choices are reframed as technical questions by some countries, while the potential of the Convention to support climate action and sustainable development through tax policy remains underexplored. Issues with clear distributional complexities are quietly treated as beyond the Convention’s scope. Whenever ambition stalls, one word inevitably appears: sovereignty. We’re told that taxing the super-rich is a domestic issue. That coordinated standards on taxing polluters would infringe national autonomy. That global rules somehow threaten democratic choice. But here’s the inconvenient truth: there is nothing sovereign about a tax system you can’t enforce. Here’s the problem: in today’s world, money, profits, and assets move faster than national laws, often through loopholes and tax havens, and across borders, while information about these assets does not. Countries trying to take action alone end up competing with each other, lowering standards, and losing billions in the process. These are funds that could have supported climate finance and sustainable development. Real sovereignty isn’t the right to say “no” alone. It’s the ability to withstand pressure together to enforce rules that protect public resources and the planet. This is why we need global tax reform. We’re living through a rupture, not a transition. The old era of club-based tax governance (dominated by a handful of rich OECD countries) is cracking under its own contradictions. At the same time, multilateralism itself is under attack, with institutional deadlock and unilateral action increasingly replacing cooperation, from the UN Security Council to climate negotiations. That’s precisely why the UN Tax Convention matters. It’s the only forum in international tax governance where every country has a seat, decisions aren’t hostage to unanimity, and tax cooperation can be anchored in sustainable development, not just capital mobility. In short: it’s the one place where we can move from fair taxation by permission to fair taxation by right. Hey reader, if you’ve reached this point it means this is a topic you’re really interested in, and we would like to know who you are, so please leave a comment below and share your thoughts! If the Convention is to live up to its mandate, four things need to happen: The tools exist. The political arguments are already being made elsewhere. And the costs of inaction are painfully visible. What’s missing isn’t expertise – it’s alignment. If governments are serious about climate justice, social cohesion and sustainable development, the UN Tax Convention is not the place to be cautious. It’s the place to be honest. Because in a world where crises are global and wealth is mobile, collective action isn’t a loss of sovereignty – it’s the only way to reclaim it. And yes, taxing the super-rich and corporate polluters is part of that story. Together, let’s urge governments to tax the super-rich and fund a green and fair future. Clara Thompson is the Global Tax Justice Lead at Greenpeace International. She is currently in New York City for the 4th round of negotiations of the United Nations Treaty on International Tax Cooperation (also known as the UN Tax Convention). Texte intégral (2501 mots)

Principles everywhere, commitments nowhere

The paradox no one wants to name

Sovereignty: the most misused word in the room

Why the UN Tax Convention matters more than ever

What needs to change

The moment we stop pretending

Greenpeace Italy unveils Olympic rings leaking oil in Milan to call out fossil fuel sponsorship of Winter Games

Greenpeace International

Milan, Italy – This morning, Greenpeace Italy activists placed a large installation depicting the Olympic Rings dripping oil and the words “Sponsored by Eni” in Piazza Duomo in Milan, where the Olympic flame is expected to arrive today. Activists displayed banners reading “Kick polluters out of the Games”, in a protest against one of the Games’ major sponsors, Italian oil and gas giant Eni, whose greenhouse gas emissions threaten winters as they are currently known and the Winter Olympics and Paralympics themselves. Photos and videos of the Greenpeace Italy protest can be downloaded via the Greenpeace Media Library Greenpeace Italy climate campaigner Federico Spadini said, “It’s absurd that the Olympics and Paralympics are partnering with corporations whose emissions threaten the ice and snow that winter sports depend on. Oil and gas companies like Eni are driving the climate crisis, and it is unacceptable that its greenwashing operations have been allowed to tarnish the Olympic values of respect for people and the environment. That’s why Greenpeace is calling for the International Olympic Committee to drop oil and gas sponsorship from the Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games and commit to ending fossil fuel sponsorship across all Olympic Games.” According to recent analysis based on scientific modelling, Eni’s annual emissions could melt enough glacier ice to fill 2.5 million Olympic swimming pools.[1] In recent days, Greenpeace Italy and Greenpeace International sent an open letter to the International Olympic Committee (IOC) asking it to ban fossil fuel sponsorships, building on its legacy of banning tobacco advertising in 1988.[2] Greenpeace Italy has also released a video denouncing Eni’s impact on the Winter Games, featuring the same image of the Olympic Rings dripping oil, as that used in the Milan installation. ENDS Photos and videos of the Olympics Rings installation in Milan can be downloaded via the Greenpeace Media Library Notes: [1] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-018-0093-1 [2] The open letter to the International Olympic Committee Watch Greenpeace Italy’s Oilympics video here Contacts: Gaia Maione, Press Office Greenpeace Italy, +39 340 571 8019, gmaione@greenpeace.org Martin Zavan, Communications Specialist, Greenpeace International, +61 424 295 422, mzavan@greenpeace.org Greenpeace International Press Desk: +31 (0)20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org Texte intégral (555 mots)

An oil and gas corporation killing winters with its planet-heating pollution is sponsoring the Winter Olympics. Could it be Eni more ironic?

Federico Spadini

We all want a world where winters remain a source of joy. A world where professional athletes and amateurs alike can count on snow and ice to pursue their passions, where children can play in the snow, and where iconic, international sporting events, like the Winter Olympics and Paralympics, continue to take place and inspire people. But the snowy scenes that provided a backdrop to so many of cherished childhood memories in Italy are under threat. The Games require the right set of conditions for competition to be safe and fair, and those very conditions are under threat from fossil fuel corporations, such as Italian oil and gas giant Eni, and their planet-heating operations. Now, in the days leading up to the 2026 Winter Olympics Milano Cortina, Greenpeace Italy has released a hard-hitting video that aims to cut through the noise and expose the threat that fossil fuels and the Games major sponsor, Eni, in particular, pose to the future of the Winter Olympics and Paralympics. The ‘Oilympics’ film shines a spotlight on Eni’s role in fuelling the climate crisis while highlighting our demand that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) ban all fossil fuel advertising and sponsorship, in order to protect the future of winter sports, and stop polluters from hijacking the Olympic spirit. Fossil fuel companies are greenwashing their image by sponsoring big sporting events to hide their destruction. Don’t let them get away with it. The short film exposes the irony of a company that is melting winter, sponsoring the Winter Games. Oil and gas corporations are driving the climate crisis, and at this rate by the 2080s over half of suitable locations will be unable to host the Winter Olympics. And Eni’s planet-heating pollution has a central role in this dour forecast. One year of Eni’s fossil fuel emissions could melt enough glacier ice to fill 2.5 million Olympic swimming pools. But the impacts go much further. Eni is currently suing Greenpeace Italy because it stated Eni harms people, after Greenpeace Netherlands calculated that Eni’s self-reported 2022 emissions could cause 27,000 excess deaths due to increased temperature alone before the end of the century. This was published in a 2023 study by Greenpeace Netherlands based on a peer-reviewed methodology. Given all of that, it’s no surprise that Eni actively seeks to hide these truths from the public, reportedly spending tens of millions of dollars on sporting sponsorships to soften its image. Buying an artificial association with the 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan and Cortina is part of that deceptive and cynical greenwashing strategy. Fossil fuel corporations, like Eni, should pay for the damage they cause, not buy reputational cover by associating themselves with Olympic values of excellence, respect, and friendship. Greenpeace supporters, nature lovers and the winter sports community are united in our desire to protect the Winter Olympics and Paralympics for present and future generations. The Olympic values of respect for people and the environment matter. Allowing Eni to use the Games as a billboard for greenwashing undermines those values and threatens the future of the event the IOC claims to support. Eni and the fossil fuel industry are driving climate change, which is jeopardising mountain communities already struggling with a rapidly changing climate, the livelihoods of many people who rely on cold winters, and the 60 million Europeans who ski every year. A better future is still within reach. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) can help lead the shift away from fossil fuels by refusing to be complicit in the deceptive practices of corporations like Eni who are stealing the winters that form the backdrop to so many precious childhood memories. This has happened before with tobacco advertising. Once the scientific consensus on the harms of smoking became too strong to ignore, the IOC banned tobacco advertising ahead of the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary. It played a key role in denormalising cigarette advertisements and set a strong precedent that was followed by sporting bodies and other event organisers around the world. It serves as a powerful testament to the power of the IOC to help shape policy at a global level and it shows that the same can be done with fossil fuel sponsorship and advertising. When iconic and influential sporting and cultural organisations like the Olympics choose integrity over greenwashing, they revoke polluters’ license to mislead and force them to face the harms they cause. That’s why Greenpeace is taking on fossil fuel corporations like Eni that are stealing our winters by shrinking snow seasons, collapsing glaciers and threatening the sports and traditions that millions of people cherish. Greenpeace is calling for the IOC to drop oil and gas sponsorship from the Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games, and commit to ending fossil fuel sponsorship across all Olympic Games. It benefits no one but oil and gas corporations; it distracts everyone from the environmental destruction they cause and the communities they harm and helps them avoid accountability. Fossil fuel companies are greenwashing their image by sponsoring big sporting events to hide their destruction. Don’t let them get away with it. Eni should be paying for the damage they have caused, not using sponsorships to polish their image while driving the climate crisis that threatens the future of winter sport. A future of icy cold winters with dependable snow is still possible, but like a glacier in the climate crisis, it’s melting before our eyes. Protecting the climate requires us to take on the forces that are destroying our winters and everything we love about them. That future is still possible if we change course now. Federico Spadini is a Greenpeace Italy Campaigner based in Milan, Italy. Texte intégral (2088 mots)

Oilympics: calling out Eni’s greenwashing

Who really pays for Eni’s greenwashing?

How do we stop oil corporations like Eni?

Bon Pote

Actu-Environnement

Amis de la Terre

Aspas

Biodiversité-sous-nos-pieds

Bloom

Canopée

Décroissance (la)

Deep Green Resistance

Déroute des routes

Faîte et Racines

Fracas

F.N.E (AURA)

Greenpeace Fr

JNE

La Relève et la Peste

La Terre

Le Lierre

Le Sauvage

Low-Tech Mag.

Motus & Langue pendue

Mountain Wilderness

Negawatt

Observatoire de l'Anthropocène

(@greenpeace)

(@greenpeace)