Greenpeace International

Texte intégral (1056 mots)

Amsterdam, Netherlands – The Inter-American Court of Human Rights just delivered a landmark decision on the obligations of States in the face of the climate emergency.[1] The Court established that governments must take “urgent and effective actions” to safeguard the right to a healthy climate, and that companies have obligations with regard to climate change and its impacts on human rights. This decision unequivocally puts the rights of people and nature above the interests of polluters.

In an unprecedented move, the Court also recognised the right to nature and ecosystems to maintain their essential ecological processes, as a crucial part in the effort to address the triple planetary crisis[2] and to achieve a truly sustainable development model that respects planetary boundaries and guarantees the rights of present and future generations.

Pablo Ramírez, Climate Campaigner, Greenpeace Mexico, said: “This is a life-changing decision for thousands of communities that are impacted by climate change on our continent. The highest court in the Americas is providing us with a pathway to climate justice, obliging States to guarantee human rights, address climate impacts and force polluting industries to repair the damage they have caused.”

The Court’s decision puts powerful legal tools to secure climate accountability and justice in the hands of more than 300 million people in 20 states that are party to the American Convention on Human Rights, including Indigenous Peoples, civil society organisations and individuals.

The advisory opinion was requested in January 2023 by the governments of Chile and Colombia.[3] It was followed by the most participatory process in the history of the Court, with 150 oral interventions from States, international organisations, Indigenous Peoples, and civil society, as well as 265 written submissions, including from Greenpeace International.

Latin America and the Caribbean are highly affected by air pollution[4], rising sea levels and extreme weather events[5], fuelled by emissions from oil and gas corporations and other polluting industries.[6]

The Court’s decision is grounded in clear scientific evidence that attributes large emissions from corporations to impacts such as loss of life and livelihoods from climate disasters. This Court decision will directly assist individuals and communities in pushing back against corporate polluters and corporate violations of human rights.

Maria Alejandra Serra, Legal Counsel, Greenpeace International, said: “For too long, politicians and corporations have gotten away with profiting from the destruction of our environment and from harming the lives of ordinary people. This decision marks the beginning of the era of corporate accountability and a big step towards dismantling the colonial legacy of systemic impunity in our region.”

The decision builds on the growing global momentum in courts tasked with interpreting international law facing the climate crisis.[7] It is expected to be used by governments to present more ambitious climate action plans and shape future decisions by other international human rights courts, setting the stage for a forthcoming historic advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice – the world’s highest court – on the responsibilities of States to mitigate climate impacts.

ENDS

Notes:

Photos and videos of Greenpeace International and its allies in the process at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights on the Greenpeace Media Library.

[1] The Inter-American Court of Human Rights, one of three regional human rights courts in the world, has the role to interpret and clarify the obligations of States. Its decisions inform national governments and courts. Read the full decision, Opinión Consultiva (in Spanish)

[2] As established by the United Nations, “[t]he triple planetary crisis refers to the interconnected challenges of climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss”. What is the Triple Planetary Crisis

[4] A review on the impact of climate change and air pollution in the region, particularly in the Caribbean, is detailed in a Columbia University publication authored by Muge Akpinar-Elci and Olaniyi Olayinka.

[5] As recently as 2024, the Americas region faced devastating effects from multiple extreme weather events, which continued to impact lives, livelihoods, and food supply chains long after the events had passed, according to a publication by the World Meteorological Organization.

[6] Written observation on the request for an advisory opinion on the climate emergency and human rights by Greenpeace International, the Center for International Environmental Law, the NYU Climate Law Accelerator, the Union of Concerned Scientists, and the Open Society Justice Initiative.

[7] Some examples are the recent decisions from the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, which classified greenhouse gas emissions as marine pollution, and the ruling of the European Court of Human Rights against Switzerland, a State failing to set adequate climate targets.

Contacts:

Tal Harris, Greenpeace International, Global Media Lead – Stop Drilling Start Paying campaign, +41-782530550, tharris@greenpeace.org

Greenpeace International Press Desk, +31 (0) 20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org

Greenpeace International

Lire plus (330 mots)

Sevilla, Spain – A growing coalition of countries have pledged to take action on taxing the super-rich and polluting companies at the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development conference.[1][2] But governments have failed to support bold measures to address the debt crisis that massively undermines Global South capacities to deal with social and environmental challenges and risks fuelling destructive extractive activities.

Fred Njehu, Global Political Lead at Greenpeace Africa, said: “Sevilla was a crucial moment for multilateralism, yet rich and powerful governments failed to match the urgency of the debt crisis hitting Global South countries, undermining wellbeing and climate action. A glimmer of hope is the new coalitions of countries that have pledged bold action to tax the super-rich and polluting corporations. These alliances are important for building momentum to unlock vital public finance beyond debt repayments.

“Now, world leaders must heed public anger over billionaire and fossil fuel greed. They must back transformative tax justice at the UN Tax Convention and COP30 to make super-rich individuals and powerful companies pay their fair share. They must listen to countries on the frontline, experts, and civil society activists throughout this conference calling for climate and tax justice.”

ENDS

Notes:

[1] Greenpeace welcomes new global initiative to advance tax reform on the super-rich

[2] New taxes on premium flyers and private jets: Greenpeace comment

Contacts:

Tal Harris, Global Media Lead – Stop Drilling Start Paying campaign, Greenpeace International. +41-782530550, tharris@greenpeace.org

Lee Kuen, Global Comms Lead – Fair Share campaign, Greenpeace International. +601112527489, lkuen@greenpeace.org

Greenpeace International Press Desk, +31 (0)20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org

Louisa Casson

Texte intégral (3184 mots)

What makes The Metals Company (TMC), a little-known company that isn’t even making any money, a threat to the ocean, international conventions, transparency and the clean energy transition?

While deep sea mining has not begun at commercial scale anywhere on Earth – and we’ve built a global movement of millions of people and political support to keep it that way – the wannabe deep sea mining bros at TMC are getting desperate, using aggressive and controversial tactics like lobbying Donald Trump to let them start their dirty business.

Here are 5 things you need to know, so we can stop them together.

1. Private interests trying to carve up the Pacific

Headquartered in Canada, with a tech-bro CEO who stands to make millions and staff overwhelmingly based thousands of miles away in the Global North, TMC wants to unleash deep sea mining in the Pacific Ocean. This would drive ocean destruction in the global commons, in a region already resisting the impacts of climate breakdown and industrial fisheries.

The company (originally called DeepGreen) has been part of a private sector push to monopolise deep sea mining exploration in the Pacific Ocean: at one point, it held rights to a quarter of a million square kilometres of the deep ocean floor.

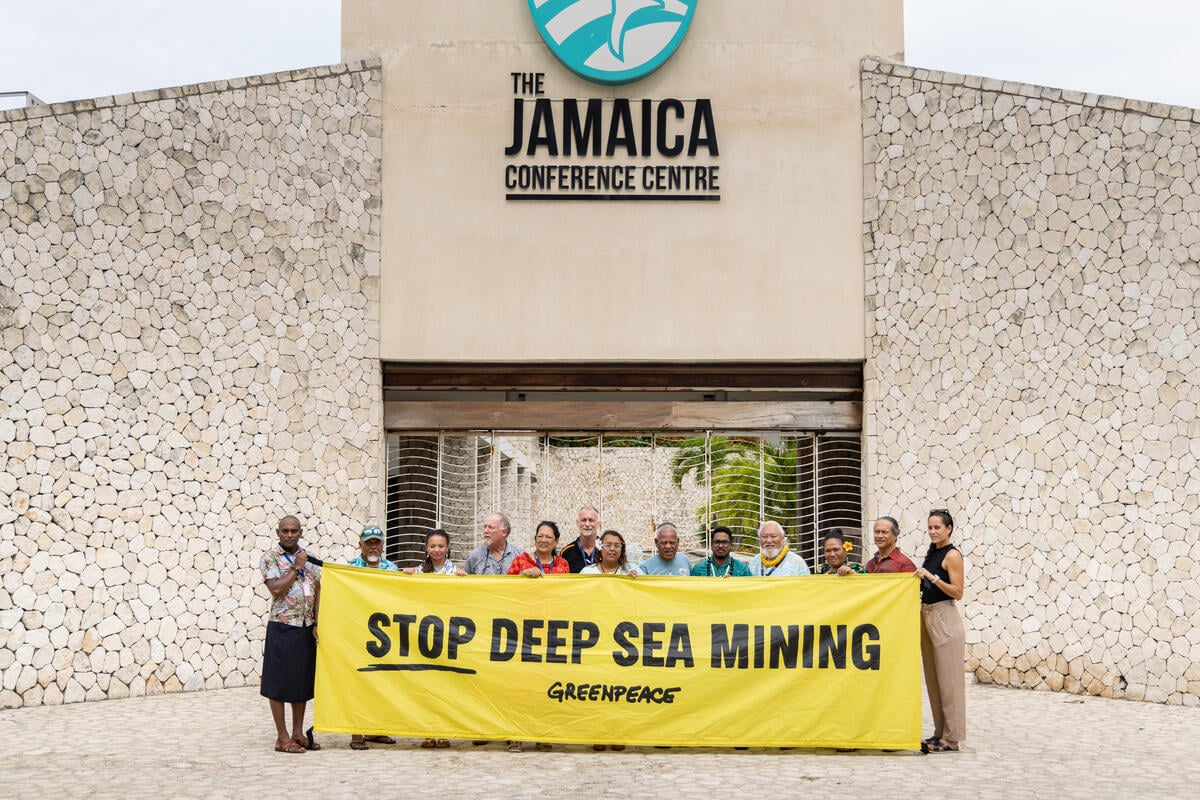

Repeating the injustices of destructive exploitation from North America and Europe, TMC has been heavily criticised by Pacific campaigners, communities and even governments for deepening neo-colonial extractivism.

CEO Gerrard Barron has tried to marginalise opposition from Indigenous Pasifika groups, claiming he’d met with native Hawaiian “elders” and “listened to their thoughts”, but dismissed them: “there’s a lot of niche groups who have a lot of thoughts, right?”

This isn’t his first rodeo either: Barron had been an early investor in a different company that tried to mine the deep ocean in Papua New Guinea, only for it to massively underestimate local opposition and go bust before they started mining. This left the island state to pick up a bill of over US $100 million.

2. TMC tried to set governments’ agenda – it backfired!

As TMC has no way of turning a profit until they get permission to start deep sea mining, political support for ocean protection has been their biggest barrier.

They lobbied hard at the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the intergovernmental regulatory body established by the UN, even shamelessly using a Pacific country’s seat at the table to tell governments, “personally, I get very uncomfortable when people describe us as deep sea miners”. But when it became clear that governments were listening to public concern and scientific warnings more than corporate interests, TMC stepped things up.

In 2021, their sponsoring state used a legal loophole which effectively delivered an ultimatum: either finish a Mining Code allowing deep sea mining to begin within two years, or TMC will submit an application with no rules in place at all. Even by the cowboy standards of the high seas, this was a “stick ‘em up!” move.

But despite tough talk, this bullying tactic actually backfired. Before TMC triggered this two-year ultimatum, no government was publicly questioning whether deep sea mining should start or not. Since TMC made this threat, over 35 governments from around the world have called for a moratorium on the start of deep sea mining.

3. TMC loved to greenwash – until they got called out by clean energy companies and scientists

If you’re trying to start deep sea mining, when love for the ocean unites people around the world and governments are agreeing a Global Ocean Treaty to protect marine life, you’re never going to win a popularity contest.

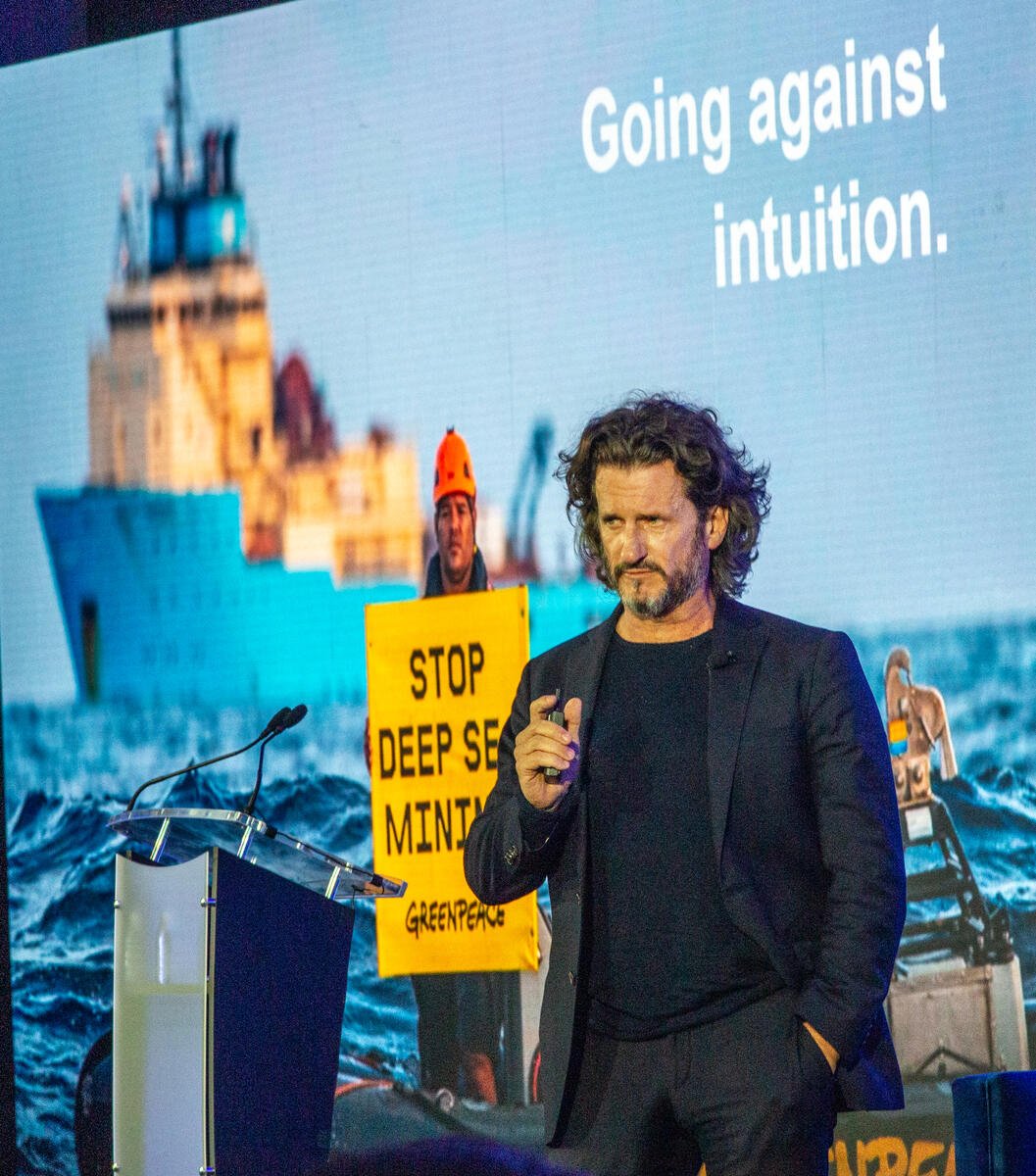

In a bid to stop people focusing on the tank-sized excavators five kilometres below the waves required to scrape up the bottom of the ocean, TMC launched a PR campaign to pitch deep sea mining as the solution to climate change. Company representatives gave hundreds of interviews, creating a false dilemma, claiming that humanity had to choose between destroying rainforests and oceans to mine minerals for car batteries. They tried to fool everyone that there was no other possible way, with Barron letting the deception slip: “Everyone’s a sucker for the story.”

It didn’t take long for the companies actually making the batteries and electric vehicles to call this out. Sixty companies, like Panasonic, BMW and Renault, have committed to steer clear of minerals mined from the deep sea and have called for a moratorium, due to the environmental risks. When an industry has such a bad rep before it’s even started, it turns out big brands don’t want to be associated with something so toxic.

What’s more, in light of scandals of mining on land, battery manufacturers didn’t turn to deep sea mining – they innovated away from the problematic minerals. In recent years, household names have committed to phase out cobalt, and new battery chemistries are surging, which don’t use three out of the four minerals TMC wants to mine from the deep sea.

Meanwhile, scientists were making more discoveries about the incredible diversity of life in deep ocean habitats that TMC wants to turn into a wasteland, learning that whales swim through these waters, and even discovering the existence of “dark oxygen”. This led to TMC following in the steps of tobacco companies and the fossil fuel industry by casting aspersions over this science, even though they had funded some of the initial research.

Showing their true colours, TMC took Greenpeace to court to try to stop our peaceful protest at sea, which disrupted their mission to collect data for their mining application. But just as we don’t back down when oil giants use legal intimidation to try and quash protests, the power of the global movement against deep sea mining was undimmed by corporate efforts to try and stop people defending what’s right. In a spectacular own goal for TMC, courts upheld Greenpeace’s right to peaceful protest not just once, but twice. A judge ruled it was “understandable” that Greenpeace International resorted to peaceful direct action in the face of the “potentially very serious consequences” of the company’s plans.

4. They’re struggling to make deep sea mining happen

Despite TMC’s own hype, deep sea mining has faced mounting challenges that paint a bleak picture of whether this industry has a future at all.

Major insurers and banks are seeing deep sea mining as too risky and staying away, while some of the big names supporting TMC at the start have fled. Danish shipping giant Maersk pulled out as a ship provider, followed by mining company Glencore selling its equity stake.

TMC has already received not one but two notices from the Nasdaq stock exchange, warning they faced delisting if their share price stayed so low and out on the water, initial tests have also been rocky. Whistleblower footage revealed that during TMC’s mining test, wastewater and debris from the ocean depths were released into surface waters of the Pacific. And that was only with a prototype machine – the Swiss-Dutch company Allseas that TMC relies on for its ships and mining machine has admitted they haven’t started funding or building full-scale mining equipment.

5. Now they’ve hitched their wagon to Donald Trump

Despite telling the media there was only a “0.1 of one percent chance” that governments would block TMC’s first mining application, it took less than three months of a scientist being overwhelmingly elected in charge of the international regulator for TMC to leave in a huff.

Despite swift and strong international pushback, TMC have now bypassed the international legal framework and are asking Donald Trump to give them permission to mine in the global oceans.

This isn’t such a surprise for a CEO who has said removing the parts of the deep sea habitat that marine life depends on is like collecting “golf balls on a driving range”. But it’s a desperate act that marks the first application to commercially mine the seabed, as not only a grave threat to the oceans, but also an act of total disregard for international law and scientific warnings.

TMC may have had a meltdown, but they’re now playing with fire. France’s ocean minister has described this as an act of piracy, and even the company itself admits that this will likely be seen as a violation of international law, creating major obstacles for them to conduct business. TMC has given governments around the world yet another reason to stop deep sea mining for good.

We need a global moratorium to stop the launch of this destructive new extractive industry. Join the Campaign.

Add your nameLouisa Casson is a campaigner at Greenpeace International.

Dr Oulie Keita and Safina Okumu

Texte intégral (1120 mots)

This story was originally posted by Greenpeace Africa.

In Nairobi’s Dandora dumpsite, Joyce, a young mother rises each day not to farm her land or build her dream, but to scavenge through plastic waste to sell and feed her children. Years of inhaling toxic fumes have damaged her lungs. Hospital visits are now part of her daily reality. Still, every morning, she returns to that mountain of waste, because she has no other choice.

Plastic waste colonialism is fuelling injustice for African communities

Joyce’s story is not an exception. It is the reality of too many African women whose lives are being shaped, and shortened, by a crisis they did not create. Women in Africa are on the frontlines of the climate and plastic crisis, not just as victims but as the invisible backbone of communities striving to survive amidst environmental collapse.

The global plastic crisis may affect us all, but its impacts are not equally distributed. Africa contributes the least to global plastic pollution, yet our rivers, coastlines, and cities are overflowing with it. Our markets are flooded with single-use plastics manufactured thousands of miles away and greenwashed as “recyclable”, “reusable”, or even “circular”. Our communities are turned into dumping grounds in the name of global trade. And the poorest, especially women, are left to deal with the toxic aftermath.

This is not accidental. It is structural. It is a system that prioritises corporate profit over human life. This is plastic waste colonialism. And it must end. Recently, Greenpeace Africa took their message to Coca-Cola’s corporate offices in Johannesburg, South Africa to demand a different future, one where corporations are held accountable and communities, especially women, are protected and empowered.

The Global Plastic Treaty must prioritise people over profit

Millions of people across the world have joined the movement for a strong, binding Global Plastics Treaty. This treaty must not be another vague agreement. It must deliver justice.

We need a Global Plastics Treaty that:

- Caps and phases down global plastic production, starting with single-use plastics

- Holds polluters accountable across the entire plastics lifecycle, from extraction, production to disposal

- Bans toxic chemicals of concern used to make plastics and waste trade from high-income to low-income countries

- Prioritises the needs of frontline communities like waste pickers, informal recyclers, and Indigenous Peoples

- Guarantees meaningful participation of African voices, especially women, in negotiations and implementation as well as a stable financial mechanism that will drive the treaty implementation

- Protects human health, especially in communities near incinerators, dumpsites, and plastic manufacturing zones

Because this isn’t just about the environment. It’s about dignity, health, and justice.

Ask world leaders to support a strong Global Plastic Treaty that addresses the whole life cycle of plastic.

Take actionIn Kenya, Greenpeace Africa’s documentary Dumped: A Waste Picker’s Story brought Joyce’s voice to the global stage. In South Africa, there are calls for legal efforts to ban hazardous single-use plastics. Across Cameroon and Senegal, we are building grassroots power to demand systemic change. We are demanding for solutions that are rooted in equity, science, and human rights.

Women like Joyce are not passive recipients of aid. They are leading change, when given the chance. Joyce and her community should not have to choose between survival and safety. And they should never bear the cost of a crisis they did not cause.

A plastic-free future is not a dream. It is a decision. Let’s make it together.

Dr Oulie Keita is the Executive Director of Greenpeace Africa.

Safina Okumu is a Content Editor for Greenpeace International, based in Nairobi, Kenya.

Greenpeace International

Texte intégral (904 mots)

Amsterdam, Netherlands – In a first, landmark test case of the European Union’s new legislation to protect freedom of expression and stop abusive lawsuits, Greenpeace International today challenges the US oil pipeline company, Energy Transfer, in court in the Netherlands.[1] The multi-billion dollar company brought two back-to-back SLAPP suits against Greenpeace International and Greenpeace in the US, after showing solidarity with the 2016 peaceful Indigenous-led protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline. The first case was dismissed, but the Greenpeace organisations continue to defend against the second case, which is ongoing, after a North Dakota jury recently awarded over 660 million USD in damages to the pipeline giant.

Activists from Greenpeace International and allies were present outside the courthouse in Amsterdam for the first hearing in the case with a banner reading “ENERGY TRANSFER, WELCOME TO THE EU – WHERE FREE SPEECH IS STILL A THING”.

Mads Christensen, Executive Director, Greenpeace International said:

“Energy Transfer’s attack on our right to protest is an attack on everyone’s free speech. Greenpeace has been the target of threats, arrests and even bombs over the last 50 years and persevered. We will continue to resist all forms of intimidation and explore every option to hold Energy Transfer accountable for this attempt at abusing the justice system. This groundbreaking anti-SLAPP case against Energy Transfer in the Netherlands is just the beginning of defeating this bullying tactic being wielded by billionaires and fossil fuel giants trying to silence critics all over the world. Something absolutely vital is at stake here: people’s ability to hold corporate polluters to account for the devastation they’re causing.”

The lawsuit is an important test of the European Union’s Anti-SLAPP Directive — adopted in April 2024.[2] The Directive is designed to protect journalists, activists, civil society organisations, or anyone else speaking out about matters of public concern, from Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPP) — unfounded intimidation lawsuits brought by powerful corporations or wealthy individuals seeking to suppress public debate.[3] Since Greenpeace International is a Netherlands-based foundation and the damage caused by Energy Transfers’s US SLAPP suit is occurring in the Netherlands, both Dutch and EU law applies.

Amy Jacobsen, Senior Legal Counsel, Greenpeace International said:

“This case paves the way for protections from bullying lawsuits being implemented throughout Europe and beyond. The lawsuits that Energy Transfer have brought against Greenpeace International are the perfect example of the kind of abusive legal proceedings that the anti-SLAPP Directive is designed to protect against. By calling upon the EU anti-SLAPP Directive’s protections, Greenpeace International refuses to allow the bullying tactics of wealthy fossil fuel corporations like Energy Transfer to compromise our fundamental free speech rights.”

At the time of the press release it was still uncertain whether Energy Transfer would appear in the hearing. The next steps are for the judge to agree on a schedule for the case.

ENDS

Photos and videos are available in the Greenpeace Media Library

Notes:

[1] The new EU rules are aimed at addressing the growing number of abusive lawsuits against journalists, media outlets, environmental activists and human rights defenders.

In February 2025, Greenpeace International initiated the first test of the European Union’s anti-SLAPP Directive by filing a lawsuit in Dutch court against Energy Transfer. Greenpeace International seeks to recover all damages and costs it has suffered as a result of Energy Transfers’s back-to-back, meritless lawsuits demanding hundreds of millions of dollars from Greenpeace International and the Greenpeace organisations in the US.

[2] EU Member States have until 7 May 2026 at the latest to transpose the rules into their national laws, but the Dutch government has indicated that the Directive’s protections can already be applied under existing Dutch legal frameworks.

[3] Big Oil companies Shell, Total, and ENI have also filed SLAPPs against Greenpeace entities in recent years. Some of these cases have been successfully stopped in their tracks. This includes Greenpeace France successfully defeating TotalEnergies’ SLAPP on 28 March 2024, and Greenpeace UK and Greenpeace International forcing Shell to back down from its SLAPP on 10 December 2024. Greenpeace Romania was being sued by the energy company Romgaz in 2025 – with the aim of dissolving the organisation, but their claims were withdrawn and they were forced to pay the court expenses to Greenpeace Romania. Greenpeace Italy and Greenpeace Netherlands are facing the Italian oil giant Eni in an ongoing court case in Italy.

Contacts:

Daniel Bengtsson, Communications Lead, Greenpeace Nordic

+ 46 703009510, daniel.bengtsson@greenpeace.org

Greenpeace International Press Desk, +31 (0)20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org

Greenpeace International

Lire plus (488 mots)

Sevilla, Spain – Spain, Brazil and South Africa today launched a coalition to advance work on taxing the super-rich at the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development in Sevilla. The coalition reaffirmed political commitments to pursue effective taxation of the super-rich. They also signalled growing support for international tax negotiations at the UN that are gaining momentum.

In response, Fred Njehu, Global Political Lead for Greenpeace’s Fair Share campaign, said[1]: “Financing is urgently needed for climate action and public services, not for polluting space travel and luxury weddings. This new coalition of governments working to tax the super-rich adds to the growing global momentum to make the world’s wealthiest pay their fair share. People are fed up with billionaires’ greed eroding the environment and communities we depend on. It’s time for world leaders to listen and act.”

Last week Greenpeace Italy together with UK Action group Everyone hates Elon unfolded a banner reading ‘If you can rent Venice for your wedding, you can pay more tax’ on Piazza San Marco, ahead of Jeff Bezos’s reportedly multi-million dollar wedding in Venice.

In a survey commissioned by Greenpeace International and Oxfam International across 13 countries, 86% of respondents want governments to close tax loopholes that benefit the super-rich and international corporations, and to use the increased revenue for public services.[2]

“Ultimately, we urge world leaders to support the on-going UN Tax Convention process as a global multilateral platform that will shape and determine the future of taxation, one rooted in equity and justice,” added Njehu.

ENDS

Notes:

[1] Fred Njehu is with Greenpeace Africa, based in Nairobi, Kenya.

[2] The research was conducted by first-party data company Dynata in May-June, 2025, in Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Kenya, Italy, India, Mexico, the Philippines, South Africa, Spain, the UK and the US, with approximately 1200 respondents in each country and a theoretical margin of error of approximately 2.83%. Together, these countries represent close to half the world’s population. Greenpeace / Oxfam – PPP survey results.

Contacts:

Tal Harris, Global Media Lead – Stop Drilling Start Paying campaign, Greenpeace International. +41-782530550, tharris@greenpeace.org

Lee Kuen, Global Comms Lead – Fair Share campaign, Greenpeace International. +601112527489, lkuen@greenpeace.org

Greenpeace International Press Desk, +31 (0)20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org

Greenpeace International

Texte intégral (729 mots)

Introduction by Mads Christensen, Executive Director of Greenpeace International:

2024 challenged me deeply, as a leader, an activist, and a human being. There were days when hope felt hard to hold on to. But what carried me – and what carries Greenpeace – is the strength of our global community and the courage of collective action.

It was a year of relentless turmoil with escalating conflicts, rising authoritarianism, climate catastrophes, and deepening human rights violations from Ukraine to Gaza. The re-election of Donald Trump only sharpened a sense of anxiety and uncertainty. It’s a moment that felt heavy – geopolitically, morally, and existentially.

And, yet, it is also a moment that reminded me exactly why Greenpeace exists.

I have never believed hope to be a passive thing. Hope is action. Hope is resistance. Hope is a decision, one that we make over and over again, especially when the odds are against us. Hope is renewal. So even as the storms intensified, our movement chose hope. We stood firm, organised harder, and achieved victories that show what’s possible when people come together with shared values and cause.

Among the highlights of the year was our contribution to the European Court of Human Rights ruling in favour of the KlimaSeniorinnen, a courageous group of elderly Swiss women who successfully sued their government for failing to take sufficient action on climate change, arguing that it endangered their health and lives. This ruling marked a turning point in climate litigation and sent a powerful message about the deep connection between human rights and environmental protection.

Our Oceans Are Life campaign built a broad coalition of governments and civil society to stop deep sea mining, a new extractive industry poised to cause irreversible harm to ocean ecosystems. We pushed Norway to reverse its plans to open its waters to mining, and convinced multilateral negotiations to put the brakes on this dangerous new frontier.

Wins like these don’t come without a cost. In 2024, corporations increasingly used legal tactics – known as Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation suits, or SLAPP suits – to try to intimidate and silence us. These lawsuits are designed to drain our time, energy, spirit and bank accounts.

Let’s be honest: being hit with multi-million dollar legal assaults is not for the faint of heart. But we are not faint of heart. Our spirit, backed by public support, is inexhaustible. Our response has been resolute, with robust legal defences mounted against these attacks. Greenpeace has never been – and never will be – a movement that backs down from a big fight. They are what we were made for.

And even as we face increasing pressure and assault from autocrats and oligarchs, we have taken the time to do the vital work of strengthening our movement from within. We’ve made real strides embedding justice, equity, diversity, inclusion and safety (JEDIS) principles across our campaigns, culture, and everyday operations. This is essential to building a movement that is global, resilient, and truly transformative.

Looking ahead, I know the challenges will not ease. But as the storm is still gathering, I also know this: Greenpeace is still here. Still fighting. Still building power, coalition, and momentum. Still choosing hope, not as an abstract ideal,

but as a bold and deliberate act.

We are powered by millions of people who know a green and peaceful future is still possible. And with that power, we will continue to adapt, evolve, and act with courage.

Progress is never easy, but it is always possible – with hope, courage and community.

In solidarity,

Mads Christensen

Greenpeace International

Executive Director

Download the reports:

Greenpeace International

Texte intégral (988 mots)

Sevilla, Spain – Barbados, France, Kenya, Spain, Benin, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Antigua & Barbuda supported by the European Commission, have announced they will form a ‘solidarity coalition on premium flyers’ to raise funds for climate action and sustainable development. Campaigners reacted to the announcement, which was made on the first day of the UN Financing for Development conference in Sevilla (FFD4).[1]

Rebecca Newsom, Global Political Lead of Greenpeace International’s Stop Drilling Start Paying campaign said: “Flying is the most elite and polluting form of travel, so this is an important step towards ensuring that the binge users of this undertaxed sector are made to pay their fair share. With the cost of climate impacts surging in countries least responsible for the crisis, bold, cooperative action that makes polluters pay is not just fair – it’s essential.”

“The obvious next step is to hold oil and gas corporations to account. As fossil fuel barons rake in obscene profits, and people are battered with increasingly violent floods, storms and wildfires, it’s no surprise that 8 out of 10 people support making them pay. Members of the Global Solidarity Levies Task Force and rich countries around the world should act upon this enormous public mandate: commit to higher taxes on fossil fuel profits and extraction by COP30, while ensuring that those being hit hardest by the climate crisis around the world benefit most from the revenues.”

Greenpeace International maintains it is critical that the revenues raised from solidarity levies in Global North countries go towards the countries and communities most affected by the climate crisis, for example through helping to fill the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage.

With demand for a climate damages tax on big polluters fast gaining momentum globally, Greenpeace urges all countries to join and implement the commitments of the new solidarity coalition on premium flyers by COP30. It also calls on all governments to adopt bold taxes and fines on greedy oil and gas corporations for the damages they have caused, without delay.[2][3][4][5][6]

ENDS

Notes:

[1] The Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD) takes place from June 30 to 3 July 2025 in Sevilla, Spain, with participation of Heads of State and Government, relevant ministers, and other special representatives. Official website

[2] Popularity of climate damages taxes on fossil fuel consumption and production. A global survey, commissioned by Greenpeace International and Oxfam International, found that 3 out of 4 people agree that wealthier airline passengers (i.e. those who fly more often, use business and first-class and or/private jets) should pay additional tax due to their outsized individual impact on climate change. The same survey found that taxing oil, gas and coal corporations for their climate damages is even more popular. 81% of people support this, while 86% support channeling the revenues from higher taxes on oil and gas corporations towards communities most impacted by the climate crisis.

[3] A call to action. The Polluters Pay Pact is a global alliance of more than 160,000 people on the frontlines of climate disasters, concerned citizens, first responders like firefighters, humanitarian groups and political leaders. It demands that governments around the world make oil, coal and gas corporations pay their fair share for the damages they cause.

[4] 80% of the world’s population have never flown. A single transatlantic flight on a private jet can produce emissions equivalent to those generated by an average person over several years. Private jets are 10 times more carbon-intensive than commercial flights and 50 times more polluting than trains. Greenpeace is calling on governments to introduce frequent flyer levies so that those who fly the most, pay the most, while preventing the expansion of the aviation industry. Private jets are an extravagant luxury which should be banned altogether.

[5] Recent Oxfam International research found that a polluter profits tax on 590 oil, gas and coal companies could raise up to US $400 billion in its first year. This compares to estimated loss and damage costs of $290-1045 trillion in the Global South annually by 2030. Further, Oxfam analysis found that the emissions of just 340 fossil fuel companies each year make up half of all global emissions – emissions of just one year are enough to cause 2.7 million heat-related deaths over the next century.

[6] Over 100 climate groups are backing a ‘Climate Damages Tax’ on fossil fuels extraction. This could be imposed by OECD countries, which if introduced at low initial rate of US$5 per tonne of CO2e increasing by US$5 per tonne each year could raise a total of US$ 900 billion by 2030 to help the world’s poorest and most vulnerable with climate damages, and pay for damages caused by some of the worst extreme weather events last year.

Contacts:

Tal Harris, Global Media Lead – Greenpeace International’s Stop Drilling Start Paying campaign, +41-782530550, tharris@greenpeace.org

Greenpeace International Press Desk: +31 (0) 20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org

Greenpeace International

Lire plus (352 mots)

Sevilla, Spain – BREAKING: Activists from Greenpeace Spain today covered the iconic Setas de Sevilla monument with a massive banner, displaying the message: “They are destroying the planet. And you are paying for it.” The action marked the first day of the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development Conference (FfD4).

Eva Saldaña, Executive Director of Greenpeace Spain and Portugal, said “Global activism is the essence of our democracy and climate justice. If we want to build a green and fair world, the people have to unite against the takeover by billionaires and polluters, and call for a redistribution of wealth and power in the multilateral arena and international financial institutions. Global justice must prevail over greed!”

ENDS

Yesterday’s release: Giant baby Musk float in march for tax justice at UN summit in Sevilla: ‘Make rich polluters pay’

Members of the Greenpeace delegation in Seville are available for interviews in Spanish, English, German, and Swahili.

Photos and Videos can be downloaded via Greenpeace Media Library and will be updated throughout the conference.

Contacts in Seville:

Tal Harris, Global Media Lead – Stop Drilling Start Paying campaign, Greenpeace International. +41-782530550, tharris@greenpeace.org

Begoña Rodríguez, Media Lead – Climate Responsibility Team, Greenpeace Spain & Portugal. +34 605248097, begona.rodriguez@greenpeace.org

Additional contacts:

Christine Gebeneter, EU Communication lead, Greenpeace CEE based in Austria, +43 664 8403807, christine.gebeneter@greenpeace.org

Lee Kuen, Global Comms Lead – Fair Share campaign, Greenpeace International. +601112527489, lkuen@greenpeace.org

Greenpeace International Press Desk, +31 (0)20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org

Greenpeace International

Texte intégral (967 mots)

Sevilla, Spain – Greenpeace activists joined a civil society march today for Global Economic Justice, with a giant float of a baby Elon Musk holding a chainsaw threatening planet Earth. As the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4) starts tomorrow in Sevilla, campaigners are calling on world leaders to advance commitments for new and fair global tax and debt rules, and to hold fossil fuel polluters accountable for climate and nature damages.[1] [2]

The conference opens against a backdrop of intensifying conflicts, geopolitical tensions, rising inequality, and accelerating climate and environmental breakdown. The outcome document, the Compromiso de Sevilla, released ahead of the conference, does not go far enough. It delivers on some promises on international tax cooperation and encouraging taxes on environmental contamination and pollution. However, bold language on sovereign debt architecture reform was weakened by Global North governments during the negotiations, and the agreement falls short on responding to the urgency of the climate, nature and social crises.[3]

Fred Njehu, Greenpeace Africa’s Global Political Lead for the Fair Share campaign,[4] said: “Sevilla is a rare opportunity for global economic justice and for urgent conversations on how billionaires and corporate polluters should pay their fair share of taxes to fund climate action, nature protection and social programmes. World leaders need to listen to what the public wants and deliver a tax system that works for all.”

Eva Saldaña, Executive Director of Greenpeace Spain and Portugal, said: “Multilateral cooperation is key to addressing global threats and resource gaps for global climate and economic justice. It must not become an excuse for more powerful governments, in the Global North or elsewhere, to water down ambition. We must put people over greed and listen to the voices rising from the streets – in Seville and all over the world. All governments must actively support the UN Tax Convention process and pursue real solutions to the debt crisis, so that we can finally begin to transfer resources away from polluters and the super-rich for the wellbeing of all people and especially for those who are suffering the most from the climate emergency.”

Greenpeace demands reforms in international tax cooperation and public financing for sustainable development. Specifically:

- Endorsement of the UN Tax Convention process for just and equitable global tax rules, that make the super-rich pay their fair share and make corporate polluters, such as the fossil fuel industry, pay for their climate damages.

- Explicit commitments from governments – via the Global Solidarity Levies Task Force, and beyond – to remove fossil fuel production subsidies and introduce progressive taxes and fines on fossil fuel corporations, and other high emitting sectors. This builds on the FfD4 outcomes document’s endorsement of “taxes on environmental contamination and pollution.” The revenues should be used to pay for domestic climate action and international climate finance support – in particular action to support communities to respond and recover from climate disasters.

Rebecca Newsom, Global Political Lead for Greenpeace International’s Stop Drilling, Start Paying campaign, said: “While fossil fuel-driven floods, storms, wildfires and droughts increasingly hit communities around the world, people are crying out for their governments to tax oil, gas and coal corporations to pay for climate-related loss and damage. So what are political leaders waiting for? They must seize the opportunity of Sevilla to make polluters pay – or face growing public anger for continuing to let dirty industries off the hook.”

Hanen Keskes, Campaigns Lead at Greenpeace Middle East North Africa, said: “This is not the time to lack ambition as civil society is calling for urgent debt relief and structural reform. The burden of debt is undermining the most vulnerable countries’ ability to respond to climate, nature and social crises. Governments must show that they are ready to build a fairer and more sustainable future – one rooted in justice, not extraction.”

ENDS

Members of the Greenpeace delegation in Seville are available for interviews in Spanish, English, German, and Swahili.

Photos and Videos can be downloaded via Greenpeace Media Library and will be updated throughout the conference.

Notes:

[1] Greenpeace Spain’s float of Elon Musk measures 2 metres wide by 3.5 – 4 metres high.

[2] The Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FFD4) is a once-in-a-decade opportunity to reform financing at all levels, including to support reform of the international financial architecture. FFD4 Conference will be held in FIBES Sevilla Exhibition and Conference Centre (30 June – 3 July 2025)

[3] The Compromiso de Sevilla: Outcome | FFD4

Contacts in Seville:

Tal Harris, Global Media Lead – Stop Drilling Start Paying campaign, Greenpeace International. +41-782530550, tharris@greenpeace.org

Begoña Rodríguez, Media Lead – Climate Responsibility Team, Greenpeace Spain & Portugal. +34 605248097, begona.rodriguez@greenpeace.org

Additional contacts:

Christine Gebeneter, EU Communication lead, Greenpeace CEE based in Austria, +43 664 8403807, christine.gebeneter@greenpeace.org

Lee Kuen, Global Comms Lead – Fair Share campaign, Greenpeace International. +601112527489, lkuen@greenpeace.org

Greenpeace International Press Desk, +31 (0)20 718 2470 (available 24 hours), pressdesk.int@greenpeace.org

Bon Pote

Actu-Environnement

Amis de la Terre

Aspas

Biodiversité-sous-nos-pieds

Bloom

Canopée

Décroissance (la)

Deep Green Resistance

Déroute des routes

Faîte et Racines

Fracas

F.N.E (AURA)

Greenpeace Fr

JNE

La Relève et la Peste

La Terre

Le Lierre

Le Sauvage

Low-Tech Mag.

Motus & Langue pendue

Mountain Wilderness

Negawatt

Observatoire de l'Anthropocène