05.12.2022 à 19:26

“Technology Transfer” and Its Contradictions: Some Aspects of Algerian Industrialization (1977)

pking

The concrete functioning of those industries which have been "offshored" or set up by "transferred technology” in Third World countries has hardly been studied in a systematic way, and we only have scattered and disparate data on this subject. It is regarding this concrete process that we would like to make a few remarks. The contradictions at work in the process of industrialization in Algeria are far from having produced all their consequences.

The post “Technology Transfer” and Its Contradictions: Some Aspects of Algerian Industrialization (1977) appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

Texte intégral (5048 mots)

The “offshoring” to the Third World of certain basic industries of the major capitalist countries, and the whole operation commonly referred to as “technology transfer” (the sale of industrial equipment, licenses, patents, know how, “turnkey” factories or factories with “produced in hand” contracts1) have been the subject of an abundant literature for several years. Most studies focus on trends in the international division of labor, the internationalization of capital and certain production cycles, and the “offshoring” of large multinationals. On the other hand, the concrete functioning of those industries which have been “offshored” or set up by “transferred technology” in Third World countries has hardly been studied in a systematic way, and we only have scattered and disparate data on this subject. It is regarding this concrete process that we would like to make a few remarks.

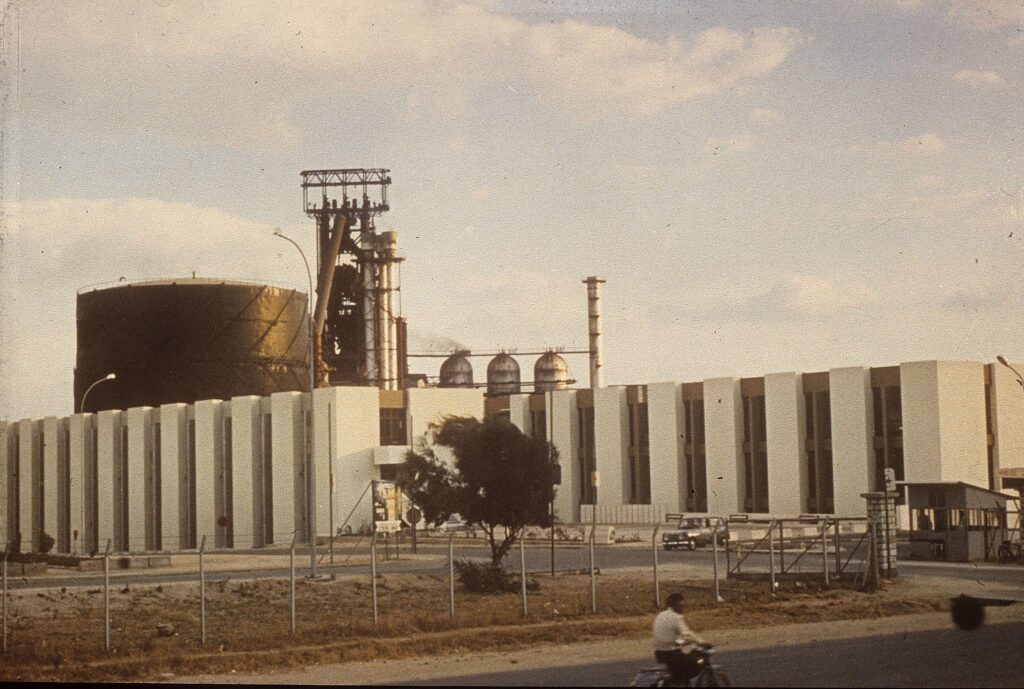

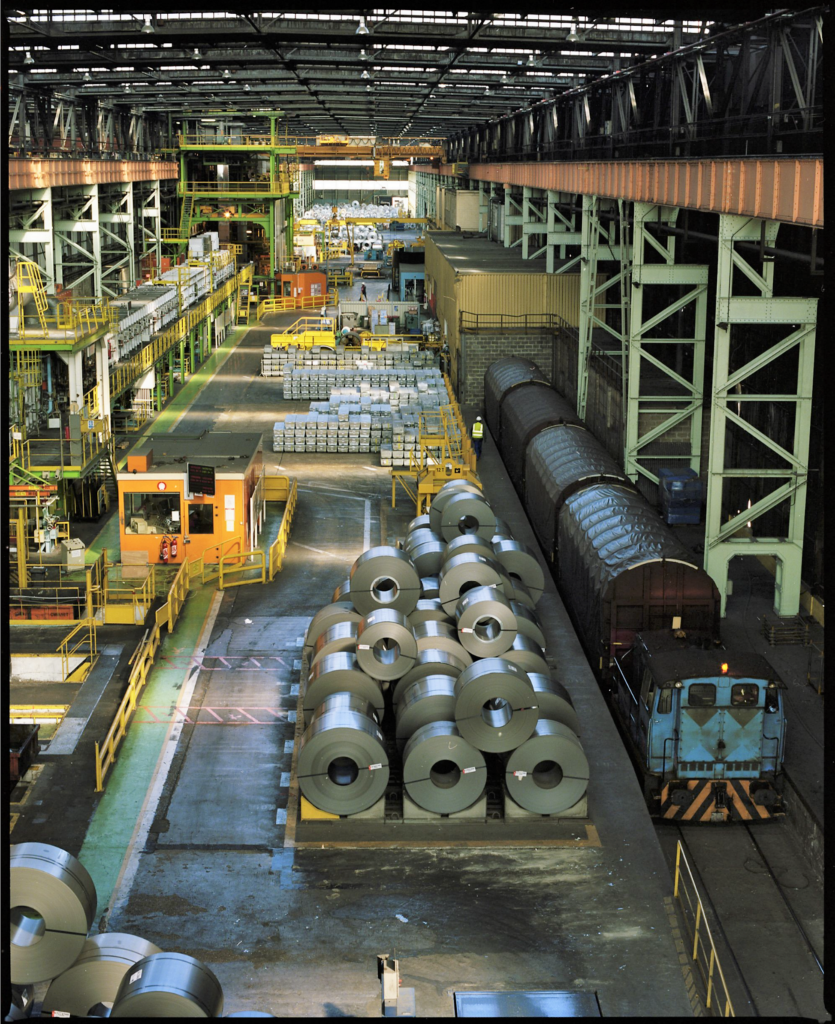

The following comments are essentially based on a research trip to Algeria in April 1974 at the invitation of the general secretary for planning. During this trip, several production units in eastern Algeria (the Annaba region) were visited, where the steel industry in particular is concentrated. This area is considered by Algerian planners as a major or even the principal “pole of development.” This trip also involved a trip to the city of Guelma, a secondary point of development in the same region.

Two facts were overwhelmingly evident during this trip. First, the reality of the Algerian industrialization effort. To an observer who rediscovered this area some ten years after his previous visit, the physical transformation of the landscape was striking, as was the emergence of a new generation of young executives vigorously engaged in the problems of technology and the organization of production.

But the other salient fact was the underutilization of newly purchased industrial equipment. Out of the four factories we visited, two were completely stopped due to supply chain disruptions, one was partially stopped due to technical incidents, and only one was functioning normally:

– The SN Metal unit in Annaba, a medium-sized factory producing wheelbarrows and towing equipment, was operating normally

– The hot rolling mill of the El Hadjar steel plant (Annaba) was halted by a technical incident;

– Production of the very modern chemical fertilizers plant of Annaba was stopped for lack of sulfur supply

– The ceramic factory at Guehna was stopped for lack of supply of imported feldspar.

The only factory to function normally, SX Metal was also, out of the four units visited, the only old factory inherited from colonization – all the new installations that we visited were in poor operation. This is an observation made without any statistical value, of course, but the magnitude of which excludes mere coincidence. All the more so, since our interlocutors reported similar difficulties in other factories in the region. These facts drew our attention to the problem of supplying newly imported industries, and generally, the problem of inserting industrial complexes purchased abroad on turnkey contracts or otherwise into a determined socioeconomic space.

The so-called ”technology transfer” problem is currently the subject of broad discussions. A “symposium” was devoted to it in Algiers in October 1973: the resulting report contains particularly interesting communications from representatives of the Algerian National Companies. It is now commonplace to point out the multiple difficulties which arise in factories bought by newly independent countries from “engineering” companies: significant delays in setting up production – which sometimes never reaches the expected level; frequent stoppages and unforeseen difficulties of all kinds. Some countries purchasing equipment are trying to overcome this obstacle by refining the contracts: contracts “produced in hand” instead of “turnkey” contracts; more precise penalty clauses in case of delays or malfunctioning, etc. However, this legal aspect of technology transfer often remains a dead letter to the extent that the relations of power are unfavorable to the buyer. The seller evades the penalty clauses by blaming all causes for delays on the buyer, and the buyer often hesitates to apply penalties for fear of open or camouflaged retaliation. The complexity of the blockages resists simple contractual precautions.

Some of the difficulties arise from causes internal to the imported production unit: production methods may turn out to be ill-suited to work habits and to the training of local labor; there is a lack of specialists and technicians; in some cases there is even a phenomenon of withholding information on the part of the “engineering” firm which, although it has undertaken to do so, does not reveal all of the manufacturing secrets …

However other causes of the blockages must be found in the totality of the economic and social environment, and the existing structure of global markets. We will now focus on this point.

It is still possible to reproduce in North Africa an exact imitation of the buildings and machines of a specific chemical factory that is currently operating in France or West Germany. But it would be an illusion to believe that we will find the same factory in Africa, simply because the plans are identical. A seemingly similar production unit functions very differently when it is located in different socioeconomic spaces and linked to different communication systems.

Modern heavy industry of the capitalist countries is today increasingly based on rapid circulation and large-scale raw material, semi-finished and finished products. This is a relatively new situation, which took shape a few years after World War II. This is due in part (and we insist on this in general) to the emergence of transporting giants which have greatly reduced the cost of freight shipping, which has disrupted the transport economy and profitability calculations in procurement policy. But it is also determined by other factors, notably the strategy of capitalist heavy industry groups, eager to use foreign trade on a massive scale to shatter internal monopolies, including those held by their own working class – especially those held by miners. Supply diversification appears as a guarantee vis-à-vis suppliers and as a weapon in case of social tension.

This trend has increased with the instability of the major world markets and the diversification of speculative mechanisms. In intensifying their foreign trade, steelmakers or chemists who “go to sea” or work with major communication routes are trying to guard as much profit as possible from abrupt fluctuations in world markets, particularly as concerns raw materials and standardized semi-finished products. This policy also puts them in a position to seize, at the lowest cost, any major technical innovation which involves changing the combination of factors of production: substituting gas for coal, one type of ore for another, etc. It should be added that these major industries generally operate continuously and that in some cases a production shutdown can result in rapid deterioration of facilities: adding another incentive to ensure the regularity and security of supply by facilitating its arrival and diversifying its origin.

For all these reasons, this type of basic industry currently requires special attention to relations with the outside world. In developed capitalist countries this requirement is met in a complex way:

– development of large industrial port zones and important road communications infrastructure, waterways and railways;

– dense telecommunications networks and systematic use of computers (keeping the order book, programming production, managing stocks, etc.; the complexity of the system is such that at the time of the merger of the two large French steel firms De Wendel and Sidelor in 1967, it took more than a year of efforts to unify their information systems and main management mechanisms);

– development of an increasingly complex system for the commercialization and circulation of capital; the growing role of commodity markets and commodity exchanges, all the more difficult to penetrate now that we see the development of increasingly speculative methods, whether it is a matter of raw materials, scrap metal, or basic petrochemical products.

It is by taking advantage of this whole system that the basic industries of the capitalist countries guarantee their regular functioning and their place in competition.

It is clear that the large heavy industrial units of the same type implanted in North Africa for instance find absolutely none of this infrastructure and environment, which correspondingly modifies their functioning and their competitiveness. We can verify this through the following two points:

1. The Ports

Fundamentally, Algeria is rather well endowed with ports. But the potentialities of the Algerian port system are, at present, (and despite recent efforts at improvement) only partially exploited. Efficacy is limited on the one side by physical impediments, on the other hand by irrational management. In terms of equipment: there is a lack of lifting, unloading, and pumping instruments, as well as of means of storage. Generally, this shortage of port equipment limits the use of the most convenient methods – for example the bulk transport of a whole set of products. In terms of management: transit of goods at the port is usually very poorly organized. Thus, there is no provision for any form of penalization of National Companies for excessive delays in taking charge of goods at the docks: hence, they tend to use the port as a temporary storage place for goods that they do not immediately need. Hence the congestion of the docks, an aggravation of the storage shortage. Waiting times for boats are lengthened before unloading, and some urgent supplies cannot be unloaded on time. There is a very slow turnaround of ships, a general scourge of Third World ports. It has been estimated that traffic jams – that could be avoided by simply rapidly removing goods stored at the dock – on its own reduces the capacity of the port of Algiers by 20 to 30%! A commission of inquiry on the port of Algiers recently drew up a heavy toll of the financial losses caused by overcrowding, and revealed real scandals: a small imported production unit had been forgotten on the port for a year and quietly abandoned machines rusted without anyone coming to look for them.

Added to this is the fact that the secondary ports (e.g. Ghazaouat, Mostaganem, Ténès, Dellys) are underutilized, all traffic being concentrated on the three main ports: Algiers, Oran, Annaba. According to Algerian statistics, Algiers alone recorded in 1970 more entries of goods than all the other Algerian ports. In large part, it seems, for reasons of administrative centralization.

All this difficult operation of the port system has, of course, a direct effect on the cost of freight, burdened with heavy demurrage.2 More seriously: in the event of tension on the freight markets, it happens that the shipowners of the capitalist countries outright refuse to send their boats to the so-called “underdeveloped” countries, preferring to make full use of their fleet between highly mechanized ports and thereby avoid problems: in Rotterdam, one can be sure that a boat will not wait more than 48 hours. Thus, in Algeria in 1974, one could see factory managers lamenting the blockage of their production because purchased cargo remained in Marseille or elsewhere awaiting transport. Conversely, when the freight market is depressed, shipowners may find it advantageous to come and cash in excess at a particularly congested port: this policy recently turned into a scandal in Lagos, forcing the government of Nigeria to take radical measures against a veritable armada of boats of all origins who tranquilly profited from a massive traffic jam they had caused …

Costly and irregular freight: insecurity of supplies, subject to the vagaries of the arms market. Here too, the balance of power is often unfavorable to Third World countries and the law of profit is difficult to thwart. The capital markets for sea freight are highly oligopolistic, with the organization of “shipping conferences” between the various companies on the main lines. Faced with this cartelization, it is very difficult for an isolated country, particularly when its port equipment is poor, to defeat the “diktats” of shipowners. It even happens that shipowners who have a monopoly on certain types of transport (for example transport of grain or refrigerated transport) are in a position to de facto prohibit certain trade between distant Third World countries, if this trade is an obstacle to interests with which they are linked.

It is because of these conditions that Algeria is trying to gain a certain autonomy in maritime transport, by building a large national fleet; in particular, it has been acquiring LNG carriers for the transport of its natural gas.

A situation of dependence and insecurity remains in place, which seems difficult to overcome immediately. The disadvantages of imported and remaining technology, highly dependent as it is on external supplies, are thereby multiplied. It is not difficult to imagine the consequences of the irregularity of supplies on large heavy industrial plants designed according to the criteria of functioning of developed capitalist countries, and thus involving major daily physical flows: supply difficulties in raw materials, spare parts, supplies of all kinds; very high cost of transport – all these are factors which contribute to raising the costs of production and constitute serious handicaps in competition on a world scale for the industries involved.

But the most immediately obvious direct effect of these difficulties has already been noted: the very irregular operation of recently imported plants.

2. Commercial Structures

The global trade structures that govern part of the supply further complicate the situation. The markets for raw materials and standardized semi-finished products (common steels, basic petrochemicals) are currently largely dominated by speculative mechanisms. In these markets, capitalism has many weapons: rapid decisions, secret trade, safe intermediaries, interconnected networks of interests, dumping, etc. By these means, it maximizes its exploitation of the rapid flow of capital and the concrete conditions for the realization of value.

Multinational corporations are obviously well placed to engage in successful operations under these conditions, especially since they themselves play a large part in creating these conditions. On the other hand, Third World countries are often in a state of inferiority from the point of view of the commercial system, purchasing techniques, and procurement procedures. We could cite many examples of failed transactions or transactions carried out on the most unfavorable terms, for lack of precise knowledge of the markets, or because of the excessive length of negotiations or procedures, or even because the dilution of powers delayed decision-making.…

At a deeper level, certain oligopolistic practices on the large capitalist world markets are deliberately closed and hermetic to the countries of the Third World.

Thus, the price of steel is worked out by complex calculations, the Brussels Stock Exchange indicating a trend from which we calculate the “extras” (premiums specified by product), the average of which is given regularly by the Metal Bulletin in London. But this is only an official base, established from known markets. However, a good part of the negotiations is secret, and the prices are established largely by direct relations, insofar as the seller and the buyer are two large economic subjects. When Thyssen sells steel to Volkswagen or Usinor to Renault, the prices and content of the contracts are hidden from publicity. A first difficulty for the steel industry in a Third World country: how to price its products (or buy semi-finished products used in the production process) when it is not directly involved in cartelization? Hence, the common temptation for the leaders of these new steelworks to bind themselves to this or that dominant force of the capitalist system, which never happens without an increase in dependency.

We can mention another factor of obscurement of exchanges and prices: triangular arrangements and the practice of “clearing.” A country delivers so many tons of sugar in exchange for a turnkey factory, and since the two are not equal, 50,000 tons of steel is added to the factory. This is common practice, and it is difficult to estimate the exact price of each component of such global contracts, some of which are, moreover, very complex and diverse. This constitutes an additional obstacle to controlling supply policy.

The world market often functions as a set of cogs and gears, which increasingly pushes the infant industries of the Third World towards working for external demands and the extroversion of the economy. In the case of heavy industry, oversized steelworks projects, inspired by profitability criteria currently in force in the developed capitalist countries, are part of this same trend. The commercial aggressiveness of countries or firms attached to developing their trade with the Third World accelerates the process. So it was with Japan, there a few years ago, bought cast iron from Algerian steelworks: shortly after, Japanese firms delivered to Algeria a giant steelworks “turnkey” project, said to be following the spirit of “rebalancing exchanges” (buying before selling is, moreover, the systematic policy of Japan in the Third World).

These then are the concrete conditions in which the new imported production units are connected to the global system. Some of the sticking points have been noted. Many others could be cited. The result remains that the extroversion of units – while it can have favorable consequences from the point of view of profitability in the developed capitalist countries – constitutes on the contrary, in the Third World, a serious danger. “Technology transfer,” as currently practiced, does not in any way guarantee the transfer of the operating conditions of the “technology” in question.

Does this mean that the newly independent countries must give up industrialization? Obviously not. Their true industrialization is essential to ending relations of dependency. But one of the conditions of true industrialization is indeed becoming not to copy large industrial units established by capitalist enterprises in the logic of their struggle on the world markets. It is up to each country of the Third World to find its own form of industrial development, at the level of production, productive methods, and types of most suitable products. It is also important to pay the greatest attention to the effective functioning of the production units put in place, so as not to install a technology that is unsuitable for integrating into the existing socioeconomic structure.

The existence of multiple blockages in the functioning of large recently imported industrial units currently constitutes of the essential problems to be solved for the Algerian authorities. The place and modalities of “technology transfer” and more generally the politics of the “poles of development” (theorized under the name of “industrializing industries”) have been the subject of many of the debates which, since 1975, have accompanied the implementation of the second four-year plan. Should we continue focusing nearly 80% of investments on three limited regions, risking thereby accentuating the exaggerated growth of these regions and the disarticulation of the economy as a whole, or should we distribute them in a more egalitarian fashion across Algeria’s territory? Must we continue to buy the most modern “technology,” or should we resort to more rustic methods of production whenever possible?

The turnaround in the world economy precipitated this crisis of conscience amidst the leaders of the Algerian economy. The euphoria of 1974, triggered by the quadrupling of the price of crude oil, was followed by a sharp drop in oil sales and revenues. The bloated purchasing programs and investment plans had to be hastily revised downwards. But quantitative reductions do not solve anything – they can even exacerbate some imbalances or bottlenecks if they are applied too abruptly. The severity of the basic problem becomes all the more pressing.

Which path will Algeria take to try to overcome these blockages? Basically, two possibilities exist and the realization of one or the other depends in the last analysis on the evolution of the sociopolitical balance of power within the country.

The first option – probably the most likely in the near future – is the pursuit of the “poles of development policy” and systematic import of equipment corresponding to the technology of the developed capitalist countries, despite the difficulties encountered. But these difficulties are too serious to be able to continue as if nothing had happened. Either way, attempts will have to be made to overcome or reduce the incidents and bottlenecks described above.

That is why “rationalization” of the management of National Societies will probably be invoked, a “rationalization” which would introduce capitalist criteria of operation, thus reducing central state control. The managers and executives of these production units are pushing strongly in this direction. Most often from the Algerian urban bourgeoisie, generally trained in Western universities and strongly influenced by the technical ideology of the large capitalist countries, they constitute a coherent and determined force; they complain of what they call the “bureaucratic straitjacket ” and call for greater freedom of movement in the management of their units, hoping to become increasingly autonomous. They criticize the cumbersome administrative procedures of procurement, the complication of customs controls, transportation difficulties for spare parts, etc. They guarantee their capability of securing much better results and of operating the industrial facilities under their control more regularly, if allowed free access to global markets and the removal of all the barriers currently established by central government control – even if it means subjecting them to a posteriori control.

A first step was taken in this direction in 1974, with the National Societies awarded block grants for purchases abroad, with freedom of action within specified limits (still relatively narrow).

If this trend continues (and the conclusions drawn from the first four-year plan seem to indicate it), the Algerian National Companies, which already concentrate most of the technicians and executives, and a good part of the qualified labor, as well as a determinant part of available financial resources, will behave increasingly as autonomous economic entities, connected to the global market but gradually isolated regarding the Algerian hinterland.

Various factors accelerate this process of empowerment: the circulation of technical information and of “experts” in the world of large modern industrial units conveys a whole ideology which accentuates the specific features and the cohesion of the technical and economic “elite”, facilitating its integration with its counterparts from other countries. Similarly, the management of the labor force tends to reproduce the organization of labor operating in the developed capitalist countries: the gap is widening, there, between executors on the one hand, executives and managers on the other. Language itself acts as a barrier: the laborer and the dock worker think and express themselves in Arabic – sometimes ignoring the French language; the plant manager and the engineer speak French and are immersed in European culture.

Is the regular operation of units assured? While such a process of increased autonomy could initially reduce certain blockages, it is not at all certain that it will solve the overall problem in the long term. The increasing integration into the world market could prove to be a trap for the units that are fundamentally disadvantaged by the lack of infrastructure and an industrial fabric comparable to those of the developed capitalist countries. Conjunctural reversals and sudden fluctuations in major markets will weigh a much heavier weight on the marginal fringes of a globally interconnected industrial system: every crisis hits them first, and with full force.

However, another way is possible. If a disruption of the current balance of social forces pushes the political forces in power to slow down this excessively dangerous process – or transforms these forces in power themselves – it could be put into action. In the disadvantaged “wilayas,“3 where “special programs” are granted piecemeal to limit surges of discontent are far from solving the problems of unemployment and poverty, constant pressure by the population in favor of more balanced development is manifest. The mass of the peasantry would like more equality in the distribution of financial resources, productive equipment, and infrastructure works. It has a dim view of the growth of hypertrophied urban centers and the emergence of privileged islands of consumption. This pressure is expressed in certain spheres of the state apparatus and political power, where occasional populist reflexes and a certain ascetic ideology come up against the demands of rising technocratism. The waste that accompanies technology transfer operations provokes reactions. As far as we can tell, these reactions are nonetheless in the minority.

It is conceivable that, following the acceleration of sociopolitical tensions, a breaking point could be crossed, new alliances could be forged within the social formation, and a certain number of choices could be called into question. The strategy of “poles of development” would be limited to the benefit of a more balanced development; investments would be distributed in a more diversified way between sectors of the economy, regions, and types of production units. Attention would be lent to the possibilities of creating small- and medium-sized units, more strongly connected to their immediate environment, both as a market and as a source of supplies. More generally, one would make as the objective internal coherence of the national economy, by relying mainly on the relations between industry and agriculture. A halt would be made on the excesses of the import of foreign technologies: greater selection in contracts, efforts to develop national technology – even those which are less “modern” – whenever possible, systematic use of local reserves of labor when they can avoid the importation of “capital intensive” techniques and materials manufactured abroad.

Can such a change of direction be achieved without profound upheavals? One cannot answer in the affirmative, especially since the interests grouped together in the first position (pursuit of the policy of “development poles” and the empowerment of large units are gaining in power and confidence. Their chance of promoting this path without a regime crisis depends on their ability to limit its immediate social cost. A difficult goal to achieve: eastern Algeria, which concentrates most of the recent industrial investments remains the area of greatest emigration from Algeria, and problems of employment, housing, and the life of the population remain acute.

Other factors are at play, including international market conditions and the results of Algerian foreign policy. The contradictions at work in the process of industrialization in Algeria are far from having produced all their consequences.

– Translated by Peter Korotaev

This text first appeared in Revue française d’administration publique 4 (1977): 123-34. Linhart wrote the piece while working as a consultant for the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies in France.

This article is part of a dossier entitled “Robert Linhart and the Circuitous Paths of Inquiry.”

References

| ↑1 | Translator’s Note: “Produced in hand” contracts refers to a new experimental legal concept created the Algerian government. See Abdelouahab Bemmoussa’s thesis on the subject: “The produced in hand contract is a juridical technique tested by Algeria to realize its industrialization. It permits a client of the underdeveloped country to simultaneously acquire working industrial equipment and the necessary skills to use it profitably.” Abdelouahab Bemmoussa, “Le contrat ‘produit en main’ – contribution a l’etude d’une technique juridique pour l’industrialisation de l’algerie,” Thèse de doctorat en Droit privé, University of Rennes, 1988. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | TN: Demurrage is a charge payable to the owner of a chartered ship on failure to load or discharge the ship within the time agreed. |

| ↑3 | TN: Algerian provinces. |

The post “Technology Transfer” and Its Contradictions: Some Aspects of Algerian Industrialization (1977) appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

05.12.2022 à 19:26

The Evolution of the Organization of Labor (1998)

pking

In the present context, what we are seeing does not really resemble the establishment of innovative organizations breaking with the Taylorist logic, but much more a mixture of genres where innovations are introduced but within a logic that remains fundamentally Taylorist. Management is engaged in a constant project to seek out another mode of control, domination, and coercion of employees before preparing the passage toward possible reforms of the organization of labor which could be rendered more compatible with the demands for responsiveness imposed by the market and new forms of competition.

The post The Evolution of the Organization of Labor (1998) appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

Texte intégral (4378 mots)

Work has changed, especially in the industrial world, where Taylorism established its credentials. With the spread of information technologies, material contact is less and less frequent for many workers, even if it has not disappeared everywhere. Tasks increasingly correspond to oversight, the monitoring of automated systems, control, the management of information and risk.

Organizational competitiveness tied to the new realities of the market and competition also exercises a determinate influence. The conditions of productivity have changed and condition another type of mobilization of employee engagement and the organization of firms: “The new forms of performance all depend on the density and relevance of the relations established between actors and the productive chains, between the functions of the firm (research office, marketing department, commercial services, production), between firms, the suppliers, and their clients, between firms and their social and technical environment.”1

The Post-Taylorist Thesis and the Emergence of New Figures of Labor

From these widely held views, some authors deduce a radical transformation of the organization of labor and even the end of Taylorism, to the benefit of the potential autonomy of workers. A current of thought has thereby taken shape, which discloses the emergence of new functions, new actors, in other words new professional identities, new arenas and new training on the basis of the significance accorded to communication, cooperation, and expertise, as well as engagement and initiative.2

The analysis of these developments is placed at the center of labor sociology, as a new factor in the workplace, and new determinant of organizational choices and competencies.

The quality of cooperation now takes primacy, information becomes the dominant feature. Workers’ skills rests with communication. It is not so much the autonomy of movements, the regularity of labor and its conformity to procedures, to the requisite prescriptions and codes which are required, but much rather a capacity to adapt to exceptional situations, an expertise which enables an appropriate treatment of the “events” which punctuate the labor-process: Reacting to events is now becoming a key component of collective or industrial labor. Qualifications are being displaced by expertise, the analysis of specific situations… One does not only communicate between tasks; the task itself consists in communicating.”3

We are far from the individual work postulated by Taylor: “The community of networked workers is in charge of its own capacity to recompose a collective knowledge,” namely, to work together, to create spaces of reciprocal understanding.4 We are far, too, from the Taylorist worker hyperspecialized in one compartmentalized task to which they are restricted. Jean-Louis Laville defines the new professional figure that has emerged in the following terms: “Office technicians, operators in automated facilities in the manufacturing industry, monitoring operators in the process industries all share the need to situate themselves in an informational series in order to locate and circulate information on which productivity and work quality will depend. Work is increasingly referring back to the culture of workers’ involvement in a universe in motion.” This culture revolves around “autonomy, initiative, the overall perception of the procedure.”5

For the team of Sainsaulieu, Francfort, Osty, and Uhalde, “the world of firms is becoming a real social milieu, where multiple ways of being are expressed in relation to the demands of initiatives and communication, responsibilities, outcomes, creativity that cover the changing life, technical complexity, and relational involvement of work.”6

These sentences from Christian Thuderoz find resonance:

Production, organization, institution: at these three levels of analysis of the firm, change is notable. Different elements are indeed combined in the workshops to sketch a new social and productive state of affairs: other ways of cooperating and self-organizing to produce, appeals to the initiative and responsibility of employees, encouragement of speech, experience in the management of flows, quality control, etc. The hypothesis of new models of organization in North America and Europe seems appropriate. The operators of automated machines and systems now react to contingencies and handle them, analyze sequences, anticipate breakdowns. Whence the importance accorded to communication between individuals, to mutual understanding.7

Moreover, this overlaps with the definition offered by Benjamin Coriat of the super-worker, at the entrepreneurial and managerial helm.8 By definition, these new workers are no longer enmeshed in the logic of prescribing means. Only the objectives remain prescribed for operators at the intersection of several specialities, tasked with a larger range of missions and engaged in multifunctional work groups where the notions of collective work, autonomy, and initiative take on their full meaning.

A Need for Caution

We can note two observations in regard to these arguments asserting a break with the principles of Taylorism in the emergence of new forms of the organization of labor. The first is that the majority of these authors have been influenced by investigations carried out mainly in the process industries, that is, a specific type of manufacturing (among them: cement production, petrochemicals, nuclear sector, steel). In these industries, organizational innovations have indeed been uncovered, notably in the sense of a real multifunctionality involving, for example, worker-technicians who participate in the improvement and optimization of production.

There have always been doubts, however, as to the very presence of actual Taylorism in these industries, considering the division of workstations is problematic given the nature of continuous work. Furthermore, these are industries where labor costs are insignificant compared to capital costs and where questions of reliability and security are paramount, imposing concessions on worker professionalism. For the proponents of post-Taylorism, there is no doubt however that series production industries are beginning to acquire some important characteristics of continuous work, namely increasingly significant investments in information and automation as well as a greater fluidity of the production process with the decrease in inventory, and that they will necessarily adopt their post-Taylorist model. Zarifian states matters in abundantly clear terms: “It is not steelmaking that we want to present as a model, but through it the demonstration of the contemporary characteristics of the evolution of the cooperative dimension of labor.”9

As for the authors who draw on observations carried out in industries of series production or in services, they evince a strong tendency to generalize on the basis of limited cases, in this instance the emergence of new functions, particularly interfaces which require more specialized communication competencies, and thus a professional know-how marked by autonomy and initiative. And moreover, was not the process of deskilling for a majority of workers within Taylorist rationalization always accompanied by the overqualification of small professional groups?

The second observation we might make is that these analyses define more of an “ideal type” than a reality, and curiously abstract from a whole fundamental part of social reality. In this optic, everything happens as if a given type of market constraint and a given type of technical tools necessarily determine a given type of work organization and a given form of employee engagement. As if Taylorism, inter alia, necessarily corresponded to a now superseded specific economic and technological conjuncture. As if, back then, there were no other possible choices.

This overlooks the fact that the forms of the organization of labor are social constructs, that is, they constitute a kind of response to the relation of forces between different actors involved in the situation, relations of forces that they effectively illustrate.

The Multiple Stakes of the Organization of Labor

Taylor never hid that the mode of organization he devised was a means of restraining the workers of the time. The scientific organization of labor thus corresponded to the institutionalization of a certain mode of compulsion, of coercion in the process of labor itself, to an organizational detour that forced workers to work not according to their own interests, but according to what Taylor presented as the good for the greatest number, the good of the nation. We know that this became above all a war machine against the workers.

In the present context, what we are seeing does not really resemble the establishment of innovative organizations breaking with the Taylorist logic, but much more a mixture of genres where innovations are introduced but within a logic that remains fundamentally Taylorist. Management is engaged in a constant project to seek out another mode of control, domination, and coercion of employees before preparing the passage toward possible reforms of the organization of labor which could be rendered more compatible with the demands for responsiveness imposed by the market and new forms of competition.

The authors who sustain the post-Taylorist current of thought all discuss a new type of labor that profoundly involves workers’ subjectivities, their resourcefulness, their communicational capacity without ever raising the question of workers’ acceptance of cooperation, of open and voluntary collaboration with management and with hierarchies. Is it definitely the case that workers, who not long ago were engaged in an ideology of class struggle (during the “Trente Glorieuses”), that is, in an open conflict declaring the non-convergence of interests between workers and bosses, today accept engaging their subjectivity in the service of the enterprise? Certain elements might lobby in favor of this hypothesis: the decline in trade unionism as well as an exceptionally high and stubborn unemployment rate. But its success does not, for all that, seem guaranteed. At least, this is the conviction that modernized management has. As proof you can point to the tremendous effort undertaken by management to “work” the subjectivity of employees, to transform an identity that appears to them still too rooted in the values of the past.

We have, for over ten years now, elaborated the idea of a paradoxical consensus to describe the dominant attitude among workers during the prior period of strong growth.10 A paradoxical consensus, because workers’ very distance in relation to the dominant rationality of the firm, their dissenting attitude prompts them to develop professional behaviors which objectively serve the interests of the firm while contesting its legitimacy, its hierarchical order, the distributions of statuses and powers that it establishes to the detriment of workers, who receive the bare bones; they have developed a whole stock [capital] of knowledge, expertise, know-how, that they clandestinely apply, in other words by resisting commands, prescriptions, hierarchical orders. In the framework of a resistant, recalcitrant, and rebellious subjectivity, they have adopted a more effective and better-adapted attitude than what was required of them by scientific management. And this is because of the reference to the profession, to the job well done, to the shared values of workers which found their collective identity, because of a will to impose, in a world of coercion and subordination, their own vision of economic rationality.11 These behaviors constitute what Jean-Daniel Reynaud calls autonomous regulation, as opposed to the regulation of control coming from management. The effective functioning of labor in firms brings results, in equilibrium according to this theory, in a complementarity between these two kinds of control, which brings about a “joint regulation.”12

Now, what is expected of these employees is consenting cooperation on the subjective plane: here there is an important shift [revirement] whose significance has not escaped managers. The challenge would be to pass to a new phase of control and domination of workers.

Contradictions

It is important to emphasize that managers are striving to develop a new type of social control, which is directly exercised on minds, on subjectivity, without actually initiating transformations in the corresponding organization of labor. We find ourselves in a specific moment of history where new forms of discipline precede, at least partially, the evolution of the organization of labor itself, which leads to a whole series of contradictions indicative of contemporary forms of modernization.

Work has of course changed, in connection with new technological tools: new practices are developing such as just-in-time production, flexibility, automatic control, first-level maintenance, the “management” of flows by operators, for instance. Tasks, as mentioned above, increasingly fall under facility oversight, operations, monitoring. But if we closely observe the new forms of labor, we notice that in the majority of cases these operations are subjected to processes of rationalization, standardization, which empties them of all professional skill and turns them into extremely routinized and simplified tasks, in the same way that the activity of oversight itself has been very codified.

The principles which carefully delineate between tasks of conception and organization, on the one hand, and tasks of execution on the other have hardly changed.

That technological development and new forms of competition open onto new possibilities in the organization of labor, that the place occupied by information flows in the labor process encourages the consideration of new modalities of definition and function does not mean, however, that these possibilities are necessarily implemented. We should not lose sight of the social dimension of Taylorism which corresponds, as noted, to an institutionalization of control and coercion in the labor process itself. Directorates for the most part do not appear, for the moment, to have renounced central Taylorist principles of the organization of labor, because they are not convinced they have access to a sufficiently reliable workforce. On the other hand, these directorates have already launched into what might be called a battle of identity to modernize employees’ minds, that is, to make them internalize the values, culture, the standard methods of reasoning in the firm, in the mode of the one best way approach to management, on the basis of the dominant rationality in the firm and excluding any debate, possible discussion, or possible alternative concerning management style.13 It is a matter of forcing workers to eschew professional solidarities, class solidarities, to embrace only the company’s values.

Even if it is done under influence (controlling and disciplining their subjectivity), directorates are consequently seeking to position employees as full-fledged interlocutors in the firm. And it is here that a very problematic discrepancy intervenes, between the effects of this approach of “enveloping” employees, of transforming their subjectivity as well as their symbolic place in the firm, on the one hand, and on the other the reality of their role in the organization of labor where they most often remain confined within Taylorist horizons, limited by still quite standardized prescriptions and definitions of procedures.

The contradictions are of two orders. Symbolic and psychological above all, since employees find themselves caught in conflicting roles (executants and pawns in the context of a very codified and prescribed organization of labor, interlocutors and actors in another time and space of the firm, that of participative groups, individual discussions with management). But very concrete contradictions, too: the prolongation of the logic of personal growth (an alibi discourse which accompanies the battle of identity and the work of subjectivity), within the organization of labor, is reflected in the keyword of accountability [responsabilisation]: each person is deemed accountable at their job post for the quality of the work they provide and the deadlines in which the work is carried out, and no longer have “management on their back” since the chains of command have been considerably streamlined by the same logic. These changes would be welcome in the framework of a post-Taylorism as some sociologists say they see it. But in the majority of cases, operators have to assume the responsibility imposed on them in what is still an extremely codified universe, where decision-making possibilities are very standardized and without help from management. Operators thus feel trapped: they are not capable of influencing the way in which their work is defined and organized, and the higher-ups, nowhere to be found, no longer provide assistance. If problems arise (breakdowns, various dysfunctions), they find themselves blocked, incapable of undertaking their job and responsibilities.14

We can advance the hypothesis that a very real misery [souffrance] is bound up with these kinds of contradictions which maintain employees in a state of permanent unease, in an exacerbated feeling of increased dependence, especially through the incredible possibilities for control offered by information technology.

– Translated by Patrick King and Paul Rekret

This text was first published in Jacques Kergoat, Josiane Boutet, Henri Jacot, and Danièle Linhart (eds.), Le monde du travail (Paris: La Découverte, 1998), 301-309.

This article is part of a dossier entitled “Robert Linhart and the Circuitous Paths of Inquiry.”

References

| ↑1 | Pierre Veltz, Mondialisation, villes et territoires: L’économie d’archipel (Paris: PUF, 2014 [1996]), Chapter 6. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Renaud Sainsaulieu, Florence Osty, Isabelle Francfort, and Marc Uhalde (eds.), Les mondes sociaux de l’entreprise (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1995); Pierre Veltz and Philippe Zarifian, “Vers de nouveaux modèles d’organisation?,” Sociologie du Travail 35, no. 1 (1993): 3-25. |

| ↑3 | Veltz and Zarifian, “Vers de nouveaux modèles d’organisation?.” |

| ↑4 | Philippe Zarifian, “Vers une sociologie de l’organisation industrielle,” Rapport pour l’habilitation à diriger des recherches, Université de Paris X-Nanterre, 1992; Philippe Zarifian, Travail et communication (Paris: PUF, 1996). |

| ↑5 | Jean-Louis Laville, “Participation des salariés et travail productif,” Sociologie du Travail 35, no. 1 (1993): 27-47. |

| ↑6 | Sainsaulieu et al. (eds)., Les mondes sociaux de l’entreprise. |

| ↑7 | Christian Thuderoz, La sociologie des entreprises (Paris: La Découverte, 1997). |

| ↑8 | Benjamin Coriat, L’Atelier et le Robot. Essai sur le fordisme et la production de masse à l’âge de l’électronique (Paris, Christian Bourgois, 1990). |

| ↑9 | Zarifian, “Vers une sociologie de l’organisation industrielle.” |

| ↑10 | Daniele Linhart & Robert Linhart, “Naissance d’un Consensus, la Participation des Travailleurs”, in D. Bachet (ed.), Décider et Agir au Travail (Paris: Cesta, 1985). |

| ↑11 | Robert Linhart, The Assembly Line, trans. Margaret Crosland (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1981). |

| ↑12 | Jean-Daniel Reynaud, Les règles du jeu: action collective et la régulation sociale (Paris: Armand Colin, Paris). |

| ↑13 | Jean-Pierre Durand, “Vers la société du post-travail?,” L’Homme et la société 109 (1993): 117-126; Danièle Linhart, Le Torticolis de l’autruche: l’éternelle modernisation des entreprises françaises, (Paris: Seuil, 1991); Danièle Linhart, La Modernisation des entreprises (Paris: La Découverte, 1994); Yves Clot, Le Travail sans l’homme? Pour une psychologie des milieux de travail et de vie (Paris: La Découverte, 1995). |

| ↑14 | Danièle Linhart and Robert Linhart, “Les ambiguïtés de la modernisation: Le cas du juste-à-temps,” Réseaux 13, no. 69 (1995): 45-69. |

The post The Evolution of the Organization of Labor (1998) appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

05.12.2022 à 19:26

Introduction to Robert Linhart: Concrete Analyses in the Spider’s Web of Production

pking

Consistent with his rejection of a romanticization of the working class, Linhart insists that workers’ knowledge is fragmented and partial, if also profound. The task of the inquiry is, thus, to collect via dialogue and participation, this disjointed state of collective memory and oral testimony in support of a systematic understanding of the whole.

The post Introduction to Robert Linhart: Concrete Analyses in the Spider’s Web of Production appeared first on Viewpoint Magazine.

Texte intégral (7744 mots)

The French Trotskyist journal Critique Communiste published a special issue in 1978 to mark the anniversary of the events of May and June 1968. It featured a lengthy interview with Robert Linhart, former leader of the Union de la Jeunesse Communiste (marxiste-léniniste) (UJCML), the organization perhaps most closely associated with the archetype of the Maoist student-intellectual, the soixante-huitard. But, in a striking shift of emphasis, rather than contribute to the litany of quixotic autopsies that characterize the period, Linhart instead pivots the discussion towards what he views as most urgent for Marxist theory, especially the need to engage in concrete inquiry into the labor process.

Some context is useful to understand what is at stake in this interview, entitled “The Evolution of the Labor Process and Class Struggles.” Robert Linhart entered the École Normale Supérieure at Rue d’Ulm in Paris (ENS), the peak of the French university system, in 1963. He soon became among the most intimate of Louis Althusser’s “student-disciples.”1 As the decade progressed, he would also become a regular attendee of Charles Bettelheim’s seminars at the École pratique des hautes études on political economy and socialist construction in the Third World.2 He sharpened his Marxist analytical chops as one of the primary editorial forces behind the journal Cahiers marxistes-léninistes, which served as a theoretico-political training ground for the group clustered around Althusser. Turning to Maoism during a summer working for the Algerian Ministry of Agriculture in 1964, in the following year, Linhart’s intervention proved decisive in reasserting orthodoxy over the Union des Étudiants Communistes (UEC).3 During the previous three years, this youth movement had become more open to the broader Marxist left under the direction of an “Italian” revisionist tendency within the French Communist Party (PCF). The “Ulmards” pro-Chinese anti-revisionism eventually led to their own expulsion from the UEC in 1966. This group of around one hundred militants, mainly ENS students, came to form the UJCML with Linhart at the helm, later that year. The UJCML first rose to prominence through the Vietnam Base Committees: these coordinated anti-imperialist organizations, formed in November 1966 and rooted in neighborhoods, schools, and workplaces, popularized the struggle of the North Vietnamese forces and National Liberation Front in the South against the United States, held discussions, published leaflets and bulletins, and engaged in solidarity actions.4 A delegation visit to China in August 1967 profoundly shaped the subsequent trajectory of the UJCML and Linhart personally. The development of a theoretical analysis came to be anchored in “établissement,” a term derived from the French translation of a speech from Mao’s Hundred Flowers campaign for the integration of intellectuals and the masses.5 Less than a year before the eruption of 1968, the group effectively turned its back on student politics to make “inquiries” by taking up work in the factories.6 Linhart himself would only become établi at the Citroën-Choisy factory in the autumn of that year.7

In May 1968, however, “our Great Helmsman Robert,” as one former comrade sardonically called him, remained at the head of the UJCML and when unrest began in the Latin Quarter, he dismissed it as a “social-democratic plot, orchestrated by Trotskyists to usurp the working class’s legitimate leadership of the struggle for the benefit of the petit bourgeoisie,” going so far as to expel his wife from a meeting for advocating in support of the student uprising.8 As such a position became increasingly untenable, Linhart underwent a severe mental health crisis, which saw him hospitalized for an extended period, just as rioting in student neighborhoods gave way to factory occupations. When, in the fallout from the 1968 revolt, the UJCML is proscribed by the state along with other left organizations, Linhart joins Gauche prolétarienne, acting as the editor of J’Accuse, one of its two journals. The practice of établissement would continue through this period, conceived in part as an inquiry in search of the theoretical principles that would triumph given their identity with workers’ aspirations and practices and not merely derived from doctrine, and to cultivate the more radical elements of the French working class.9

While Linhart judges this span of political work harshly in the interview, J’Accuse was a significant left-wing publication. It advanced a militant yet popular journalism that sought to comb the political relays that had continued after May ’68 between intellectuals and working-class strata. Its opening editorial averred that its content would be “oriented toward reality, in other words expressing what the press is silent about or distorts. It is a matter of telling the truth about the violent battles the people put up against those with power in this world, the truth too about the low-level everyday war waged against…work ‘accidents,’ living conditions, HLM-dormitories, the foyers-rackets[.]” The weekly was to be “popular through its methods,” and correspondents were encouraged to “physically connect with the reality of peasant and working-class revolt, to articulate the currents of contestation that are transforming the different layers of French society.”10 The project of sustaining viable organs of counter-information that could transmit the intelligence of ongoing social struggles remains one of the GP’s most enduring legacies and certainly can be felt in Linhart’s later work.

In “Evolution of the Labour Process and Class Struggles” Linhart describes the permanent state of crisis of the GP as a “much more dialectical type of organization,” whose own existence and form was perpetually in question; one that sought to break with activity designed mainly to accumulate political capital for the militant, as he puts it, rather than seek out the conditions for revolution. But Linhart is also critical of the militancy of this period for its truncated focus on the spectacular; a blinkered, even “pathological” view of reality prevailed, he argues.11 This is a worldview which, according to Linhart, has its watershed around 1972, when the GP is dissolved and its members, along with the wider milieu, are faced with a return to “ordinary” life. For his part, Linhart would return to the academy, spending most of his career teaching sociology at Université Paris-VIII-Saint-Denis.

It is partly in light of conceptions of revolutionary struggle developed through the Cultural Revolution and against the backdrop of the decomposition of the French left that in 1976 Linhart publishes perhaps his most important text, Lenin, the Peasants, Taylor, offering a nuanced and account of the Bolsheviks’ shifting analyses and policies vis-à-vis the Russian peasantry and developments in industrial production.12 Among its most fecund arguments is one revolving around Lenin’s adoption of Taylorist scientific management as a means of developing Russia’s productive forces. In conceiving the party as the political agent of the working class, the latter’s objectification by a bureaucratized, Taylorized labor process is justified on the grounds that newly won efficiencies in production would free the popular masses to participate in the direction of the state. The Russian turn to Taylorism, Linhart argues, thus lay the conditions for a rupture between an authoritarian labor process and the democratization of political institutions.13

We can discern in such a claim the echoes of earlier concerns over the separation of intellectuals from workers, and of the division of mental and manual labor more generally, as developed within the UJCML and GP. These are made explicit in Linhart’s discussion of the fear of the peasantry among the Russian revolutionary intelligentsia whose romanticized adoration of the countryside quickly turns to disgust following their bad reception there. This is a characteristic move for the petit-bourgeois intellectual, Linhart notes, a sentiment witnessed among those who entered the factories in the 1960s “with the religious fervor of men for whom absolute truth has been revealed, and after a difficult experience or defeat, abandon their établissement by declaring that the workers are bourgeois, rotten, or fascists.”14

What, then, was Linhart’s own response to Mao’s injunction for the intellectual to “dismount to look among the flowers” or “settle down” among the workers, where a revolutionary situation is absent? In this respect, “Evolution of the Labour Process” unpacks at some length the method of “inquiry.” This is to return to the term deployed by the UJCML but, by the late 1970s, while still conceived as an operation “at trench level”, still établi, in a manner of speaking, but effected through a scholarly work that seeks to understand contemporary transformations to the conditions of labor. The strategies, experiences, and setbacks of établissement allowed could lead into more adequate apprehension of workplace organization and sociabilities.15

Linhart offers a two-fold line of reasoning for the urgency of such a method and unpacking this here serves to begin to offer a sense of how it functions. First, capital operates with an increasingly sophisticated capacity to obscure reality, to restrict or manipulate knowledge of production. Second, production and circulation themselves grow in complexity as outsourcing and subcontracting extend these processes ever more widely and the divisions and differentiations of labor become ever more intricate and stratified. What might appear as a given, discrete factory or enterprise to an outside observer, Linhart suggests, might involve a whole array of small subcontractors operating across an assortment of sites with vastly disparate working conditions and very different operations. Failure to grasp this is to retain a viewpoint anchored in what remain in many respects “craft” sections of the working class within certain sectors – steel working, auto production, cement making… This is a form of ideology, as Linhart sees it, insofar as it excludes from its frame of reference the “spider’s web” of fragmented labor, some “core,” others “subaltern,” that make it up. It is on this basis that knowledge collected from workers is essential in order to gain crucial, systematic knowledge of “the whole” of specific processes of production today. Consistent with his rejection of a romanticization of the working class, Linhart insists that workers’ knowledge is fragmented and partial, if also profound.16 The task of the inquiry is, thus, to collect via dialogue and participation, this disjointed state of collective memory and oral testimony in support of a systematic understanding of the whole.

Linhart’s investigative throughlines combine specific insights from the roughly contemporaneous efforts to develop a practice of workers’ inquiry and “co-research” in Italy, namely the attention to workers’ subjectivities and the “fractures” introduced into class composition through circuits of migration and the variegated enforcement of job hierarchies. Recent scholarship has traced the diffusion of Italian workerism in France, particularly via the publication of translated Quaderni Rossi articles in the 1968 Maspero collection, Luttes ouvrières et capitalisme d’aujourd’hui, as well as the influence the inquiry-form – as fact-finding, interviews, collective tracts, or questionnaires – would have on far-left groups embedded in the social upsurges of the period.17 Linhart’s elaboration of his approach to inquiry in the 1978 interview allows us to see its resonances with that of a figure like Romano Alquati, who stressed the need for close relations between an “outsider” with deep-seated links to “insiders” at a particular worksite. When Alquati went into Olivetti in the early 1960s, he had contacts with workplace militants active in the local branch of the Italian Socialist Party to lend their expertise and assistance. Alquati grounded his inchieste in discussions with workers themselves, drawing out hypotheses and leads that interacted with shop struggles and bringing in broader layers of workers across plants and job classifications.18 The cultivation of close ties with informal work groups around specific knots of firm-specific issues and labor processes raised the collective analysis to a political level. Likewise, Linhart’s careful introduction of the “core/periphery” world-systems problematic to the differentiation of workforces across a production complex also gestures toward the research Ferruccio Gambino and others were conducting in the mid-1970s on how the “mobility of labor-power” and the “mobility of capital” constituted “complementary aspects of the fractionation of labor,” hardening forms of segmentation and closing down openings for working-class organization.19 Finally, Linhart’s insistence that the introduction of new technology into work relations is always a matter of rebalancing the nexus of capitalist power, integration, and workers’ insubordination finds reverberations with Raniero Panzieri’s criticism of distortions around Marxist views on technological development, the division of labor, and workers’ control.20

“Evolution of the Labor Process and Class Struggles” provides a series of examples of how the move from fragments to system might function, although it bears remarking that it does not take up the literary form of an episodic first-person narrative that Linhart otherwise adopts in The Assembly Line, his account of his time établi at Citroën, or Sugar and Hunger, his analysis of the sugar-growing region of Pernambuco in Brazil.21 In the latter, for instance, he offers a rich narrative of his travels through the region as a means of examining the ways an industrialized, sugar-based monoculture wipes out small plots, draws local producers into global markets and class relations. His tapestry of dialogues is expansive, extending to children (themselves often waged workers), a union president, local politicians, engineers, plantation owners; it’s a mode of analysis that operates at different levels of abstraction and, in “settling down” in this way, seeks to avert a reification of Marxist concepts by starting instead from lived experience. This is a means of analysis, in other words, which offers the resources to overcome the apparent contradiction between objective knowledge and a class perspective.22

Not long after “Evolution of the Labour Process and Class Struggles” was published, Linhart largely retreated from public view following a suicide attempt, and with the exception of The Assembly Line, little of his oeuvre has been translated to English.23 It is important to note, however, that Linhart did not completely abandon this commitment to militant inquiry in the later phases of his itinerary, but sustained it through other channels. As he perceptively remarked in a conversation with Charles Bettelheim and the journal Communisme in 1977, there exists a “fantastic disproportion between certain theoretical debates over Marxism and the capacity to understand the concrete class struggle today.”24 Linhart has continued to survey this struggle in its different levels: from international transformations in the process of accumulation, the increasing mobility of capitalist firms and the multiplication of subcontracting, the state’s role in social regulation and labor legislation, different strategic approaches and accommodations from the trade unions, to the strategies of exploitation, spatial division, and resistance that make up the everyday antagonism of the working day.25 He contributed to the lively debates in France at the onset of the 1980s and the arrival of the Mitterrand government into power over the future of the trade-union movement, the destruction of shop floor cultures, and the ideological obfuscations around the Auroux Laws and the devising of new lean production-based “employee participation” schemes.26 He co-wrote reports with other researchers and labor activists involved with the major trade union centers – including his sister, Danièle Linhart, a prolific sociologist of the shifting patterns in the subjectivity of work and managerial techniques centered around the rerouting of autonomy. Through networks and think tanks like the Association d’enquête et de recherche sur l’organisation du travail (AEROT) and the Centre pour la recherche économique et ses applications (CEPREMAP), he made connections with other currents of Marxist analysis of the labor process, recasting the themes and approaches of sociologie du travail in contexts of crisis and restructuring.27 Across all of this activity, he has tackled these scientific analyses of the tendencies of capitalist development, the management and control of labor-power, and workplace organization from the “viewpoint of the working class…among the agents of the production process.”28

In the texts assembled in this collection, Linhart upsets familiar periodizations regarding Fordism and post-Fordism, Taylorism and post-Taylorism, globalization, and other broad characterizations about the changing character of work. He hits upon critical features of contemporary political economy and the labor movement: the redistribution and maintenance of forms of exploitation through outsourcing, arcane legal arrangements of flexible employment, and offshoring in many industries; the interplay of autonomy and subordination in work relations; management surveillance, stress, and knowledge capture in partially automated worksites; and the prospects of worker militancy and union organization among fissured or segmented workforces in larger production and logistics concentrations, across smaller, low-wage shops, and on regional or geographic bases.29 Included are investigations carried out at petrochemical complexes around the Étang de Berre;30 a report on the development of capital-intensive industry and the dilemmas of technology transfer in Algeria, from a visit to the country in the mid-1970s, broaching the the logistical and political questions raised by relations of dependency and underdevelopment in the global value chain;31 historical overviews of Taylorism and consideration of the methodology of the enquête; an inquiry conducted among hospital workers during the transition to the 35-hour workweek in France, tracking the contradictory upshot of computerization and standardization on the labor process in the medical field; and analyses of the structural effects immigration, imperialism, and racialization have had on divisions among the proletariat in France. Linhart has continually highlighted the significance of militants immersing themselves in these situations of investigation and struggle.

This article is part of a dossier entitled “Robert Linhart and the Circuitous Paths of Inquiry.”

References

| ↑1 | Louis Althusser, The Future Lasts a Long Time and The Facts, eds. Olivier Corpet and Yann Moulier Boutang, trans. Richard Veasey (London: Chatto & Windus, 1993), 221. See too Julian Bourg, “The Red Guards of Paris: French Student Maoism of the 1960s,” History of European Ideas 31, no. 4 (2005): 472-490. In an interview with Peter Hallward for the Cahiers d’analyse project which resulted in the Concept and Form volumes (London: Verso, 2012), Etienne Balibar details the seriousness and depth with which Linhart approached the history of Marxist theoretical and political practice from very early on: “Linhart was intoxicated with politics and with Leninism. A little younger than us, he had marked his entrance into our group (the Cercle d’Ulm) in a spectacular way, showing that he knew almost the whole of Lenin’s work by heart. Linhart more or less identified with Lenin. He had read the thirty volumes of his complete works, and memorized them.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | François Denord and Xavier Zunigo, “‘Révolutionnairement vôtre.’ Économie marxiste, militantisme intellectuel et expertise politique chez Charles Bettelheim,” Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales 158, no. 3 (2005): 8-29. |

| ↑3 | Virginie Linhart, Le Jour Ou Mon Père S’est Tu (Paris: Seuil, 2008). For some of Linhart’s writings during this period (including a summing-up of his visit to Algeria), see Robert Linhart, “On the Current Phase of Class Struggle in Algeria,” trans. Peter Korotaev, Cosmonaut Magazine, November 2021; and a 1966 text which originally appeared in Charles Bettelheim’s journal, Études de planification socialiste, “For a Concrete Theory of Transition: The Political Practice of the Bolsheviks in Power,” trans. David Broder, Rethinking Marxism 33, no. 4 (2021): 476-511. |

| ↑4 | See Ludivine Bantigny, “Hors frontières. Quelques expériences d’internationalisme en France, 1966-1968,” Monde(s) 11, no. 1 (2017): 139-160; Kristin Ross, May ‘68 and Its Afterlives (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 90-95; Nicolas Pas, “‘Six Heures pour le Vietnam’: Histoire des Comités Vietnam français 1965-1968,” Revue historique 302, no. 1 (January-March 2000): 157-185. |

| ↑5 | See Mao Zedong, ‘Speech at the Chinese Communist Party’s National Conference on Propaganda Work” (1957), Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, Vol. 5. |

| ↑6 | UJCML, “On Établissement,” (1968), trans. Jason E. Smith, Viewpoint Magazine 3 (2013). |

| ↑7 | Robert Linhart, The Assembly Line, trans. Margaret Crosland (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1981). For a different salting experience in a car factory, see Fabienne Lauret, L’envers de Flins. Une féministe révolutionnaire à l’atelier (Paris: Syllepse, 2018). |

| ↑8 | Jean-Pierre Le Dantec, Les Dangers du Soleil (Paris: Les presses d’aujourd’hui, 1978), 112; Virginie Linhart, Volontaires pour l’Usine: Vies d’Établis (1967-1977) (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2010), 38-9. |

| ↑9 | For an excellent overview in English see Jason E. Smith, “From Établissement to Lip: On the Turns Taken by French Maoism,” Viewpoint Magazine 3 (2013), and Donald Reid, “Etablissement: Working in the Factory to Make Revolution in France,” Radical History Review 88 (Winter 2004): 83-111. For other accounts, see Marnix Dressen, Les établis, la chaîne et le syndicat. Évolution des pratiques, mythes et croyances d’une population d’établis maoïstes 1968-1982 (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2000); the articles collected in the thematic issue of Les Temps Modernes, “Ouvriers volontaires: les années 68, l’«établissement» en usine,” nos. 684-685 (2015); and Laure Fleury, Julie Pagis, and Karel Yon, “‘Au service de la classe ouvrière’: quand les militants s’établissent en usine,” in Olivier Fillieule, Sophie Béroud, Camille Masclet et Isabelle Sommier, with le collectif Sombrero (eds.), Changer le monde, changer sa vie. Enquête sur les militantes et les militants des années 1968 en France (Paris: Actes Sud, 2018), 453-484, 2018. |

| ↑10 | See F.M. Samuelson, Il etait une fois Libé (Paris: Seuil, 1979), 100-101. See too Michael Witt, “On and Under Communication,” in A Companion to Jean-Luc Godard, ed. T. Conley and T. J. Kline (Hoboken-Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014). 318-350, for more on Linhart’s role in J’Accuse and its impact on the filmmaking of Jean Luc-Godard. |

| ↑11 | For an earlier, quite bitter and unforgiving version of this line of criticism contra “gauchisme,” see Linhart’s takedown of Deleuze and Guattari’s 1972 text, Anti-Oedipus: Robert Linhart, “Gauchisme à vendre?,” Libération, December 7, 1974, 12, 9. |

| ↑12 | Robert Linhart, Lénine, les paysans, Taylor (Paris: Seuil, 1976). Rare analyses in English are offered by Dimitris Papafotiou and Panagiotis Sotiris in “Rethinking Transition: Bettelheim and Linhart on the New Economic Policy,” Rethinking Marxism 33, no. 4 (2021): 512-532 and Alberto Toscano, “Seeing Socialism: On the Aesthetics of the Economy, Production and Plan,” in Economy: Art, Production and the Subject in the 21st Century, ed. Angela Dimitrakaki and Kirsten Lloyd (Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press, 2015). |

| ↑13 | Linhart, Lénine, les paysans, Taylor, 91-94. |

| ↑14 | Linhart, Lénine, les paysans, Taylor, 60; it is worth comparing with Linhart’s own work on the Brazilian peasantry in Le Sucre et la Faim. Enquête dans les régions sucrières du Nord-Est brésilien (Paris: Minuit, 1980). |

| ↑15 | In this endeavor Linhart’s work overlaps with that of fellow ex-établi Nicolas Hatzfeld: see his reflection “De l’action à la recherche, l’usine en reconnaissances,” Genèses 77, no. 4 (2009): 152-165; as well as the ethnographic approaches of Michel Pialoux and Stéphane Beaud. See Stéphane Beaud and Michel Pialoux, Retour sur la condition ouvrière. Enquête aux usines Peugeot de Sochaux-Montbéliard (Paris: La Découverte, 2012 [1999]); Michel Pialoux and Christian Corouge, Résister à la chaine. Dialogue entre un ouvrier de Peugeot et un sociologue (Marseille: Agone, 2011); and Michel Pialoux, Le temps d’écouter. Enquêtes sur les métamorphoses de la classe ouvrière, ed. Paul Pasquali (Paris, Raisons d’agir, 2019). |

| ↑16 | See Enes Kezluca, “Theoretical Acupunctures: From Althusser to the Post-Althusserian Marxism of Robert Linhart,” Rethinking Marxism 33, no. 4 (2021): 533-562. |

| ↑17 | See Marcelo Hoffman’s excellent study, Militant Acts: The Role of Investigations in Political Struggles (Albany: SUNY Press, 2016). Hoffman focuses on Dario Lanzardo’s Quaderni rossi article, translated for the Maspero volume as “Marx et l’enquête ouvrière,” in Quaderni Rossi, Luttes ouvrières et capitalisme d’aujourd’hui, trans. Nicole Rouzet (Paris: Maspero, 1968), 109-31. |

| ↑18 | See Romano Alquati, “Organic Composition of Capital and Labor-Power at Olivetti (1961),” trans. Steve Wright, Viewpoint Magazine 3 (2013), and the historical commentary of Steve Wright in Storming Heaving: Class Composition and Struggle in Italian Autonomist Marxism (London: Pluto Press, 2002), 54. Alquati’s methodological notes in Per fare conricerca: Teoria e metodo di una pratica sovversiva (Rome: DeriveApprodi, 2022 [1993]) are also worth revisiting. An excerpt was translated for the indispensable 2019 South Atlantic Quarterly section on militant inquiry, edited by Matteo Polleri. See Romano Alquati, “Co-research and Worker’s Inquiry,” South Atlantic Quarterly 118, no. 2 (April 2019): 470-78. |

| ↑19 | Ferruccio Gambino, “Class Composition and US Direct Investments Abroad,” Zerowork 3 (1974). See too Gambino’s comments on the subject in his interview with Dylan Davis, “The Revolt of Living Labor,” Viewpoint Magazine, November 2019. |

| ↑20 | See Raniero Panzieri, “The Capitalist Use of Machinery: Marx Versus the ‘Objectivists,’ ” trans. Quintin Hoare, in Outlines of a Critique of Technology, ed. Phil Slater (London: Ink Links, 1980), 44-68. |

| ↑21 | Robert Linhart, The Assembly Line and Le Sucre et la Faim. For a helpful commentary on the latter work, see Marcelo Hoffman, “A French Maoist Experience in Brazil. Robert Linhart’s Investigation of Sugarcane Workers in Pernambuco,” Cahiers du GRM 16 (2020). See too Robert Linhart, “Dette, l’ouvrier et le paysan au brésil,” CEPREMAP Working Papers, no. 8903 (1989). |

| ↑22 | On this point see Kezluca, “Theoretical Acupunctures: From Althusser to the Post-Althusserian Marxism of Robert Linhart.” Also see Louis Althusser’s coruscating comments on “concrete analysis” and workers’ inquiry in What is to Be Done?, ed. and trans. G.M. Goshgarian (London: Polity Press, 2020), 1-24. |