Texte intégral (8974 mots)

Everyone knows the oceans are changing. Sea levels are rising, the water’s getting hotter, coral is disappearing. But what does that actually mean? What impact are the changing oceans having on humans? Hannah Stitfall is joined by climate activist Shaama Sandooyea, who explains how climate change is impacting her home nation of Mauritius, and grammy-nominated DJ and environmental toxicologist Jayda G travels to the studio to tell Hannah about her new CNN film, ‘Blue Carbon.’

Presented by wildlife filmmaker, zoologist and broadcaster Hannah Stitfall, Oceans: Life Under Water is podcast from Greenpeace UK all about the oceans and the mind-blowing life within them.

Listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music or wherever you get your podcasts.

Below is a transcript from this episode. It has not been fully edited for grammar, punctuation or spelling.

Shaama Sandooyea (Intro):

One of my fondest memories is me standing on the beach in Flic en Flac in Mauritius, which is on the west coast. This is the beach where I used to go with my parents and my family during summer trips.

This is one of my most favourite beaches because of the memories, because of the laughter of the people there because of the scent, the smell of the food, the whole place is just amazing.

But unfortunately, that the change over the past decades because of the beach erosion, so we lost actually a huge amount of beach, small island developing states, we are being affected so much by the climate crisis to the point that the land is being reduced. And yet we are barely contributing to it. So the way that we see climate change in in other countries is very serious as well. But small islands came to a point where it’s disrupting the society there. It’s disrupting the way of life and the way that the people function.

Hannah Stitfall:

This is Oceans: Life Under Water, a podcast series that brings the oceans and the incredible life within them right into your headphones.

I’m Hannah Stitfall. And in this episode: Changing Oceans. We all know that climate change is having a huge impact on our seas. Trawling alone emits as much CO2 as the whole aviation industry. But away from the scary stats, what do the changing oceans actually look like?

Shaama Sandooyea (Intro):

It’s a huge part of us to be from Mauritius. Because wherever you are around the world, and you see Mauritan, the joy that you have. But having that be stripped away is is ripping off our identity of ourselves.

Hannah Stitfall:

Is there any hope?

Jayda (Intro):

Blue carbon essentially is where various plants within an ecosystem they’re really good at pulling carbon out of the atmosphere and storing it into the ground where it stays. We’re basically giving them like a new press release. We’re like, come on guys. This is like the big new, like environmental ecosystem that we should be really paying attention to.

Hannah Stitfall:

This is Oceans: Life Under Water, Episode 11.

I’m really pleased to be joined today by Shaama Sandooyea. Shaama is a marine biologist from Mauritius. She staged the first ever underwater climate protest to highlight the impacts that climate change is having on Mauritius, an island nation in the Indian Ocean, and it gives me great pleasure to welcome into the studio Shaama. Hello!

Shaama Sandooyea:

Hello! How are you?

Hannah Stitfall:

I’m very well! Where are you?

Shaama Sandooyea:

I’m currently in Serbia. I’m not in Mauritius at the moment.

Hannah Stitfall:

Oh, I see. Is that where you’re living then?

Shaama Sandooyea:

Yes, at the moment. Yes.

Hannah Stitfall:

A bit different from Mauritius.

Shaama Sandooyea:

Well, it’s not surrounded by the ocean. So yeah, it’s quite different.

Hannah Stitfall:

Tell me where you’re from. I mean, for some of our listeners that might not have ever had the opportunity to go to Mauritius. I mean, I never have, I would love to. Tell us what it’s like. What does it look like? What does it sound like? Tell us a bit about Mauritius.

Shaama Sandooyea:

Okay, so I might be sounding a bit nostalgic, when I’m talking about it because I love my country so much. But basically Mauritius, as all of you probably know is it’s an island. It’s a small island. And it’s found right in the middle of the ocean in the Indian Ocean. And it’s like on the south eastern coast of East Africa, East of Madagascar, and it’s really a dot on the map. But I also like to say that Mauritius is not just a small island, but it’s actually a large ocean state because it has 2.3 million kilometres square of exclusive economic zone which is like maritime zone and everything. Mauritius itself is the main island but we do have smaller islands around like Rodrigues, Agaléga, St Brandon, Chagos and Tromelin. And probably Mauritius is also famous for the dodo.

Mauritius for me, it’s a country that has many facets. So, the first thing that I say when I think about Mauritius is the beauty, the multicultural, the diversity of the people, of the languages, of the way of living. So, there is this part of Mauritius that is abundant with life. You have the endemic plants, you have insects, you have the birds that are flying by the mountains, you have the wetlands. They are sheltering, migrating birds from Europe basically. They are very important for us. We also have mangroves that are protecting the coastline so they are like these trees that are guarding the coast of the island. And of course we have sea grasses, sometimes you can catch a seahorse there. We have the coral reefs. And these coral reefs, they are home to the most diverse ecosystems on the planet, different types of fish of eels, sea turtles, that’s one side of the country that, that I really like to put forward like this, this quality of life, this diversity of life that exists there, the colours, the green forests, the green mountains, and also the blue ocean. And this is just fabulous.

But unfortunately, there is also another side of Mauritius, which is a bit damaged. We have, of course, social issues, a lot of inequalities on the island, but when we focus a bit more about the environment, there is a part of Mauritius that is, that has been pretty much destroyed. I would say since since the colonisation of the island, by the Dutch, British and French, of course, at the time, they were not fully aware of the environment and the importance of protecting it. So a lot of our natural endemic forest has been cleared. And also, of course, the dodo were killed and a lot of animals started disappearing because of that. For example, we had dugongs in the Mauritian waters. But of course, sailors started killing them to feed.

So there is also the side of the island that I really want to have in mind. Because when I speak of about Mauritius, to anyone, everyone is actually very excited about it, Oh Mauritius, it’s perfect! Yeah, yeah, it is beautiful. And I cannot I’m always amazed by the diversity of life, every time I’m seeing a new fish, I’m super excited about it. But also there is this part that is destroyed. And I want to raise awareness on it so that people can understand, Okay, this is beautiful, this is natural, this is paradise, but also we have other issues behind and these issues, they are growing faster than the country can recover faster than the animals can recover. So this is how I would like to describe Mauritius. It has plenty of faces, multifaceted, but beautiful.

Hannah Stitfall:

I mean, it sounds wonderful. Sign me up! Sign me up. I want to go there right now. So for some of our listeners that may not know what a small nation island is, can we can we just expand on what that actually means?

Shaama Sandooyea:

Well, of course! The most common term that is used for that is ‘small island developing state’. So basically, there are many small islands that are developing countries around the world, whether it’s in the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian Ocean. You do have like small land territories, if I can say that. But the ocean is, they have a bigger ocean territory, but they’re just like, very small lands.

And they share challenges that are quite similar, whether it’s social, environmental, or economical. Like, for example, on the islands, on the small island developing states, there are limited resources, we don’t have as enough resources as any other bigger country. And that’s a problem because we need to import. Import products, we depend on in our international trade, whether it’s for food, whether it’s for transportation, or for development and everything. So there is that.

There is also the fact that the small islands, they are quite a way far away from from the mainland. So in terms of travelling, transportation, it’s very complicated. For example, when you’re living in Europe, you’re living in the US or Australia or Asia, whichever, like a big continent, you can travel, you can travel and it’s fairly easy. But to get out of Mauritius, for example, you need to have the aeroplane. So it’s always that remoteness that is very challenging. I know for example, a lot of Mauritians that never left the country, and probably never will because it does cost a lot of money. So we have that as well.

And we have the fact that most of these islands they are they are located on subtropical latitude, but the problem is that these places they are more susceptible to natural disasters, like heavy rainfall, cyclones, typhoons, etc. So having these conditions which make them more prone to disasters, and knowing that there are limited resources on the island, it’s complicated for recoveries, complicated for even to be prepared for these things and then to recover.

Also, these islands they they are not just limited in terrestrial resources, but they have a vast maritime resources like like really big maritime zone and a lot of these islands depend on the ocean. Depend on the ocean for food, depend on the ocean for travelling, depend on the ocean for, for just being, as part of their culture as part of who they are. So that’s mostly how I would describe the small island nation.

Hannah Stitfall:

And tell us a bit about what’s happening with the small island nations and climate change.

Shaama Sandooyea:

Okay, so even if all small island developing states, they are facing the same challenges, not all of them are being affected by the same way, by climate change. If we take the example of Vanuatu, if we take the example of some other islands in the Pacific, of course, sea level rise is, is gonna be a huge problem for them, a huge crisis for them because it’s a flat island, so it’s easier for them to be swallowed. But for example, in Mauritius and Reunion Island, we are mostly volcanic islands, and we have mountains we have higher lands. So of course, the sea level rise is going to affect us as well, as it is already – it’s eating a lot of our beaches, but there is still land for us to move to there is still this, there will still be Mauritius, Mauritius will still exist on the map. But it’s just that, of course, when the sea is rising, when the sea level is rising, people are going to be displaced, they’re gonna lose their homes, they’re gonna lose everything. And this displacement is not something that we have enough space for or enough capacity, resources, especially in terms of money. So the challenges are quite complicated.

Also, it depends a lot on… well, we know that every year we have climate phenomenon like El Nino or La Nina. So that also really influences the climate on the islands. In one way you can have, for example, the El Nino we had the El Nino for the summer of 2023 to 2024. And the masquerade islands, Madagascar, we, we witnessed, like an obscene amount of rainfall of water coming from the sky. And it was so serious that the rainy season started way earlier. It started since November. And usually it starts around January, February. It started since November, and almost every week, the government had to close schools because it’s too much water. It’s risky. There were many, many accidents, and you cannot just let people go out when it’s raining that much. And we had some severe cases, not just in Mauritius, but in Reunion Island as well, in Madagascar, where houses are flooded completely people don’t they are pushed out by the water. And they don’t know what to do it was it was very traumatising for the people. Also, at the same time, if we have, for example, La Nina, well, it’s going to be drier condition, which means that we don’t have water.

So even if we do our best to prepare and adapt for it, it’s something that we are limited to adapt to it, we for example, the piece of land that we have is not going to sustain 200 millimetres of water in 24 hours. It’s never going to do that. But also another thing is, of course, when we talk about rain, we talk about drought, we talking about food security. So a lot of a lot of these islands, they have some small plantations, even if they cannot plant like everything. But the extreme climatic conditions make it really hard to grow anything. And even if we managed to do it, where the prices are just going to skyrocket because it’s too… it’s not growing well or it’s bad. So this is these are the main points that I will say about how climate change is affecting small island nations.

Of course, I’m not even mentioning about the social issues that come behind it, but it’s a lot.

Hannah Stitfall:

And just for our listeners at home, El Nino and La Nina are just extreme climatic events.

Shaama Sandooyea:

They are actually natural currents that occur. They are just the different length. El Nino is a different direction and La Nina is a different direction. So these currents they occur in the Pacific Ocean, and they influence the weather a lot in South America, in Australia, east of Asia, and of course Africa as well. For us in the Indian Ocean. If we have El Nino, it means that we’re going to have warm currents and with a lot of humidity and rain, but La Nina for example, in Mauritius, in Africa, of course, it’s small, drier conditions. But if it’s drier for us, then it’s also more typhoons for Southeast Asia. These are like natural currents that exist already. But they influence the climate a lot on the neighbouring countries and with climate change is becoming extreme.

Hannah Stitfall:

And how often is it an El Nino or La Nina year? Is that Is it just every every other year?

Shaama Sandooyea:

No. For example, for the past three years, we’ve actually had La Nina consecutively because yeah, it was a bit problematic for African countries because they had long droughts, but it’s not necessarily one year El Nino and another year La Nina, it can be for example three years La Nina and one year El Nino.

Hannah Stitfall:

Yeah, cuz I was gonna say you know if it, if it is one year one and one year the other then, you know if it was raining raining a lot, then you could sort of, you know, store that water to see us through the next year but you know if La Nina lasting three years. That’s serious drought, isn’t it?

Shaama Sandooyea:

And yeah, it is it is serious drought. And that’s why for the past few years, we’ve seen like horrible drought conditions in African nations like unbelievable, but also now we can see that they are being flooded because of the of the rain and everything.

Hannah Stitfall:

We’ll come back to Shaama in a second because I want to bring back on Richard. Richard’s a maritime lawyer and he was my guest in episode 6, about the Wild West of the High Seas. At one point our conversation turned towards island nations. I’d asked him how rising sea levels were threatening the rights of island nations like Maritius and what maritime law says about protecting them. And I thought his answer was really interesting.

Richard Caddell:

That’s something that’s currently being worked out. Because one of the big problems of the law of the sea is that it was largely written in the 1970s where climate change wasn’t on anybodies serious agenda. I mean, obviously, there were scientist looking at it, but it certainly wasn’t permeating international negotiations in a way that it does now.

Ultimately, when it comes to these small island states, there is a school of thought that says that your boundaries will recede as your countries recede. So if part of your coastal defences start to erode, and those sorts of things, and so your maritime boundaries come back, and the real sting in the tail, is that an island state, for instance, if it is no longer habitable or able to support economic life of its own, then it’s classed as a rock and it loses its maritime entitlements.

So at the moment there is a lot of international litigation ongoing, and there are three separate international courts looking at the issue. But a lot of the small island states are arguing that the maritime boundaries should be fixed at a point before climate change starts to affect them so they don’t lose those entitlements. But of course there is a very real risk that these countries could become eventually, if nothing much is done drastically, could become uninhabitable within the space of, you know, centuries, certainly, two.

Hannah Stitfall:

What do you think? Do you think they should have their boundaries fixed?

Richard Caddell:

I think there is a strong legal argument for that and you can base that on a legal principle of equity, fairness, that those are the boundaries that were fixed in time when we signed this convention, so those are the boundaries that should remain there. But ultimately, that would of course be challenged by more enterprising and more geologically solid states that have been eyeing their resources and seeing an opportunity. Unfortunately human nature is human nature.

Hannah Stitfall:

Ok, back to Shaama…

If Mauritius, as a small island nation, if it were to become unlivable at one point, because of the effects of, of climate change, how would that affect your identity?

Shaama Sandooyea:

I mean, how would you feel about that, and I guess other people from Mauritius, the thing is that we are already feeling it. Because like I mentioned earlier, we had some pretty serious rainfall for the summer 2023/2024. And you don’t recognise your home anymore, you don’t recognise the island anymore. Like it’s destroyed, your house is destroyed. The island where you see is destroyed, the ecosystems are destroyed. And you feel a sense of, of danger, of insecurity, because you’re not sure if you can still be here in the next 10 years. And for sure, if you want to have kids, you’re not even sure they will be able to live here or to sustain themselves here. Like what is the future of the people there? What is the future of the next generations? And, and that’s something very hard because we are I mean, we are Mauritians, we are from an island, we see life differently, but also at the same time, it’s a huge part of us to be from Mauritius. Because wherever you are around the world and you see Mauritians, the joy that you have that someone is from an island is here next to you. It’s amazing! But having that be stripped away is, is ripping off our identity of ourselves. It’s a big thing for us.

Hannah Stitfall:

And are you hopeful for the future of Mauritius?

Shaama Sandooyea:

Ah, well, not so much.

Hannah Stitfall:

Oh!

Shaama Sandooyea:

Um, yeah, I’m very sorry about it. I am not hopeful at all because when we look at the picture of how Mauritius is, it’s an island that has been destroyed for the past 400 years probably. And we don’t have enough political will or enough strength to actually make a change. I’m very, I’m criticising always, I’m criticising the government and also the private sector because they are profit driven, they are not driven by the future of the island. Because if they were, they would actually work together with, with the communities there, with the people there, with the workers on the island. But it’s not happening that way is always a system of profit driven. And also at the same time, Mauritius is, I mean, all the states, they are not even contributing to 1% of the climate crisis. It’s not proportionate at all! I mean, whatever we do, even if we start planting a lot of trees on the island, okay, it can help us when we want to, I mean, for example, we want to adapt to the situation of higher heavy rainfall, planting trees and mangroves, it’s actually going to help us to adapt to it and to be stronger to be more resilient. But at the same time, for example, like I mentioned, when we have 200 millimetres of water falling down from the sky, how do we do it? How many trees do we need for it? So there is this part where we are not in control of the climate crisis at all, we are not, we cannot do anything about it for now. I mean, we can advocate for it, we can push, we can pressure the world leaders, we can pressure them, we can push our government, we can pressure the private sector to stop depleting the ocean like that. But I am not hopeful at all about the future of the island. And now we’ve come to a point where they’ve built so many houses on the beach, that they are going on mountains, to build hotels and villas there for wealthy people. I mean, if Mauritians cannot afford housing in the country, why? Why are we doing these things? But that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be hopeless about it. I feel hopeless about it. But that doesn’t mean I should, I should just let it go. Because that’s what that’s what they want us to be hopeless and not do anything and just let them get away with it.

Hannah Stitfall:

Right, so Shaama? We know, things are pretty bad. Yeah. How can we stop it?

Shaama Sandooyea:

Oh, there are so many things that can be done. Okay. So there are things that we all can do by ourselves. Although I believe that it’s not big enough to make a change. I’m very sorry for saying that. I’m trying not to break the morale here. But for example…

Hannah Stitfall:

Give me some hope!

Shaama Sandooyea:

Like switching the way that we consume things, increasing our awareness about it, this is very important. But also, we need to know that every action does not have the same impact at every level. For example, when I’m refusing to eat meat, when I’m refusing to use plastic, okay, it’s going to reduce the amount of CO2 of emitting all the plastic and putting in back in nature and everything. But also at the same time, there is a huge cooperate there still producing plastic and giving to others. So the most consequent actions I can suggest is to take it up to politics, to take it up to the corporates, to the companies that are destroying constantly destroying areas because of the resources because of the oil, the oil industry, keep the pressure on the oil industry keep the pressure on where the government’s on, on world leaders that are refusing to acknowledge the need for climate urgency, because they keep on admitting and they don’t know, but it’s affecting us here in Mauritius, for example. So these are my line of actions that I would highly recommend to people. And I believe that if we keep doing that we they will need to change but yeah, that’s my take on it.

Hannah Stitfall:

Oh there you go, for all our listeners at home. That’s our call to action. After you’ve listened to this you’ won’t’ll need to email your MPs get in touch with everybody.

Shaama Sandooyea:

Yeah, and literally everyone, everyone has to be on board with this.

Hannah Stitfall:

Well listen Shaama thank you for coming on today and speaking to me, it’s been it’s been brilliant talking to you actually. Mauritius, I guess, I guess for me, you know, being in England and some of our listeners it seems like a world away and and of course it is one of the frontline places in in climate change. So thank you very much. It’s been really good talking to you. Thank you.

Shaama Sandooyea:

Well, thank you as well. And thank you all, to all the listeners for for paying attention and then doing what’s what needs to be done. Thank you so much.

Hannah Stitfall:

So what can we do? Are we headed for a future where our island nations disappear? I mean, that’s all a bit of doom and gloom, isn’t it? But I’ve got someone else in the studio with me now, who says the answer to that is No.

Jayda G is a Grammy nominated DJ and music producer from Canada, as she also happens to be an environmental toxicologist. Her film Blue Carbon comes out on CNN later this year. And it gives me great pleasure to welcome Jayda to the studio! How are you?

Jayda:

Hi! So glad to be here. Thanks for having me.

Hannah Stitfall:

Thank you for coming on. I mean, I’ve been working in wildlife stuff for a while now. What is an environmental toxicologist? What is that?!

Jayda:

I know, it’s so funny, it’s like on like, my description on Instagram. And like I was talking about it on like, some Instagram real and someone was just like, Yo, what is actually an environmental toxicologist? Like, that’s a great question.

Yeah no, it’s basically the study of chemicals and how they affect our environment. So it could be how it affects plants, how it affects animals, and the ecosystem as a whole. Yeah, super fun.

Hannah Stitfall:

I mean, it’s a it’s a fascinating, fascinating life. Because as I said, you know, you don’t you don’t think of somebody being a DJ in, you know, playing all these amazing gigs and Grammy nominated, but also really interested in like chemical reactions.

Jayda:

Yeah, nature as a whole.

Hannah Stitfall:

And that, but that’s our fault. That is our fault. You know, you stereotype people. And we do it every single day. And yeah, you know, you can be really, really cool, but also really interested in nature.

Jayda:

No, I’m just really nerdy, like across the board.

Hannah Stitfall:

So, Jayda, tell me about your film that’s coming out with CNN later on this year.

Hannah Stitfall:

Yeah, Blue Carbon, I’m so excited about it. It has been in the makings for a number of years now. Yeah, so Blue Carbon is an environmental documentary, where I’m kind of like the host, the main person, you come along a journey with me where I learn about blue carbon ecosystems. And blue carbon ecosystems are these environments that are really good at pulling carbon out of the atmosphere, and putting it into the ground. So they’re amazing at combating climate change. And I go around the world kind of discovering these different ecosystems and how they can help our world essentially.

Hannah Stitfall:

Because I mean, blue carbon, I mean, how would you describe that for our listeners that might not have heard about it.

Jayda:

Totally, what is blue carbon? Blue carbon, essentially, is where various plants within an ecosystem on coastal ecosystems are really good at pulling carbon out of the atmosphere and storing it into the ground where it stays. And it helps that whole ecosystem basically live and thrive. And blue carbon ecosystems include mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrass meadows. And we talked a lot about this on the film, like kind of like the skin to our land, like, it creates a barrier so that it really helps the mainland from kind of like storms and hurricanes and things like that. So these are very important ecosystems.

Also, they are like 10 times better at pulling carbon out of the atmosphere than like the Amazon rainforest. So they were basically giving them like a new press release. Like, come on, guys. This is like the big new, like environmental ecosystem that we should be really paying attention to. Yeah. And blue carbon essentially, is not blue. Just so you know, in case you were curious! Because it’s really just, you know, these plants that are really good at pulling carbon and putting into the ground. So it’s just like this muddy, like soil that’s very just thick. And yeah, has a whole amazing ecosystem that goes along with it.

Hannah Stitfall:

I love that analogy. You know, that it’s the skin of the land.

Jayda:

Yeah, it’s really cool. It really just, it really emphasises the importance of it. These are definitely not ecosystems to be overlooked. But they have been for a long time because they’re not maybe like the most like sexy environments.

Hannah Stitfall:

They’re important! Mud is important!

Jayda:

Mud is important!

Hannah Stitfall:

So what would happen because I know they, they themselves, they store a lot of CO2, they pull it out?

Jayda:

Yes, yes.

Hannah Stitfall:

What would happen if we, if we lost…

Jayda:

Yes, if we lost those ecosystems, it would emit a tonne of carbon out into the atmosphere essentially. So it’s not only just trying to grow and protect these ecosystems because they are good at pulling carbon, CO2 out of the atmosphere. But if we lose them, we lose what in biology you would call a carbon sink, you lose these areas that are holding and storing a tonne of carbon and when you lose those areas, that means more carbon in the atmosphere.

So about 67% of the collective mangroves, seagrass meadows and salt marshes have been lost.

Hannah Stitfall:

Oh!

Jayda:

Yeah. So it’s a very high number. They’re, yeah, they’re so important. So it’s kind of like we need to get our butts in gear. Yeah.

Hannah Stitfall:

Yeah. And I mean, you do see, you know, places they turn their mangroves into….

Jayda:

Yeah, they totally decimate them.

Hannah Stitfall:

You know, people with yachts can go there.

Jayda:

Totally and it’s like, I don’t know why, but humans really love to completely re make these really muddy. I don’t know, these marshy areas into parking lots. Yeah. I don’t know what it is about that. But um, yeah. And that’s kind of what this film is about, where it just really highlights the importance of these ecosystems and that we should really look at protecting them.

Hannah Stitfall:

For the film, you must have travelled all over the place. I mean, I was reading you went to you went to Vietnam to France to Brazil. Tell us about some of the stories when you were filming and some of the some of the people you met.

Jayda:

Oh, my goodness. So it was really cool because the production company and the director Nicholas Brown, they really wanted me to experience the whole film, like how the audience is going to experience it. So literally, like, as you are seeing the film, I’m like learning about these ecosystems like along with you.

So the first place we go to is Vietnam, and we learn about how, during the Vietnam War, when they were spraying Agent Orange everywhere, it completely decimated all of the mangrove forests there, which are so so important to protecting Ho Chi Minh City. And we end up meeting this man, Dr. Nam, this guy was just like, such a G. And he had been hired by the government of Vietnam, to literally just go and replant the mangroves. That’s what his job was, like after the Vietnam War. So he spent all the 70s and 80s. Learning how to plant mangroves literally just like from scratch, like there’s all these photos of him just like this, like old dugout canoe, just like putting the mangroves in and figuring it out, like in real time. And it’s he replanted the whole forest, like it was successful. That’s the craziest part. So just like that’s just like a tidbit of some of the crazy stories that we learn in this film.

Hannah Stitfall:

Where else, how many countries did you go to?

Jayda:

Yeah, so Vietnam, Brazil, obviously, Senegal, we ended up going to. I ended up being in Colombia, that was an amazing experience. And they also do a profile in France as well. And also the states of Florida. So six countries.

Hannah Stitfall:

When when you were there, and obviously spending, spending time with these communities that rely on the oceans, and are very, very entwined with them. I mean, what did you personally take away from spending time with them?

Jayda:

Yeah. So much. The number one thing I took home, and this kind of changes, like every day, because it’s like, you’re constantly processing this insane experience. But just how important community is, how important it is to work together on something. That’s something we really highlight in the film. And it’s kind of like the solution to everything. That when you band together and have agency, the ability to make good decisions for your community, things really start coming together.

Hannah Stitfall:

And I’ve heard that in the film, you mention carbon credits schemes. I mean, this is the first time I’d heard of them. I’m sure some of our listeners might have heard of them. For anybody that hasn’t, can you just explain a bit about what they are?

Jayda:

Yeah. So carbon credit schemes are essentially where it funnels money from people who are emitting carbon to people who are taking carbon out of the atmosphere. That’s like the basic.

Hannah Stitfall:

So basically it’s a bit like offsetting your air miles.

Jayda:

Kind of. Basically. But it’s a bit more detailed than that. But basically, we profiled this community in Senegal, where there are companies that hire people in Senegal who live near the mangrove forests, to they take money from that company and pay people to actually plant the mangroves. So that’s essentially it and then as we go through the film, we talk about the pros and cons of that scheme. So where does the money actually come from? How much do people get paid? Do the people who are actually planting the mangroves? Do they have agency on who they get to choose from who’s paying them? Those kinds of questions, and we really dig deep into that and find some pretty interesting solutions. So yeah.

Hannah Stitfall:

Because I mean, yeah, in the film, you are showing that these systems, yeah, they don’t currently work. There’s, there’s a lot of a lot of bad stuff about that at all. And, you know, these big companies, for them, it’s just, it’s just a box ticker, you know. And also, it’s not a like for like, you know, mangroves take years and years to grow.

Jayda:

Exactly like Dr. Nam in Vietnam, took multiple decades to replant this forest that was completely decimated during the Vietnam War. And it’s not something that happens over like, a couple years. It’s something that happens over many, many, many years. So yeah, it’s about protecting these ecosystems, what we have already, growing more so that they can flourish. And really understanding that this isn’t yeah, a tit for tat situation, that there’s a lot of time, energy, and a lot of love that goes into these ecosystems.

Hannah Stitfall:

And you were saying earlier that communities that they’re picking and choosing which companies that they…

Jayda:

Yeah in Colombia they are, yes.

Hannah Stitfall:

And that’s really, really cool. Because, you know, as I said, you know, the big companies, I guess they come in, it’s just a box ticker for them. We’ve done the carbon credit scheme, that’s it. So it’s good that the people on the ground are able to work with companies that I guess, do understand that this is an investment, and it’s going to take time, and they’re not just, they actually care.

Jayda:

Exactly, yeah. And it’s such a more holistic view, I guess that’s like, I think the one of the things I was really struck by because you have the communities, you have researchers working there, you have the government working there, and you have the companies. So it’s so interesting, because for me personally, because I got my masters in natural resource and environmental management. And you learn about stakeholders. Stakeholders are people, all the different kinds of people who are invested in that resource. And there’s each person or area, whether it’s the government, whether it’s people who live there, etc. have their own take on that. And Colombia is really a great example of all the stakeholders coming together in a common value to actually protect, save and preserve these ecosystems for for the greater good of the planet.

Hannah Stitfall:

And I know that the film is there, there’s a lot of hope in the film.

Jayda:

Yes. That was a big reason why I want to do this.

Hannah Stitfall:

Do you think that there is hope?

Jayda:

Yeah, totally. It’s even before I did this film, like I remember working in my, with my professor who was the main environmental toxicologist in that department. And he would always say, like, there are so many hopeful stories out there within the research. It’s just anyone who works in academia knows this by the time like, someone has found whatever it is the thing that’s positive within, you know, the area that they’re working in, it takes sometimes a decade for that to reach, like to public knowledge.

So there are a lot of really positive stories out there, where we’ve discovered something about this chemical, and now we know how bad it is. And then there are all these policy restrictions now, within that country that keep it from using it. Like there’s a lot of really cool stories like that. And this film is along a similar track where it really talks about, you know, obviously, like the really bad things about climate change. We all know about it. It’s not pretty, it’s really depressing in a lot of ways. But there are ecosystems that are really good at combating it. And there are ways of really galvanising, those ecosystems basically, by empowering the people who really live and breathe within those ecosystems to take care of their home, essentially.

Hannah Stitfall:

Yeah. And when people start to take care of the ecosystems more, it makes them more resilient. You know, it’s not half the battle, but it’s but it’s part of the battle.

Jayda:

Exactly. It’s a good, it’s a very healthy start. Yeah.

Hannah Stitfall:

And have you had any, any first hand feedback back from say, some of your fans that know you for your music. Have you had any of them, you know, reach out to you and say, you know, I’m now interested in the environment, I had no idea.

Jayda:

Oh, yeah, totally like, the nice thing too, was just hearing how there’s so many people out there who also work in sciences. And they’re so interested in dance music as well. They love to dance music. And yeah, it’s just how they both kind of reside in these two worlds. And they just get really happy to see someone who is the same. So yeah, yeah, camaraderie.

Hannah Stitfall:

I know a lot of people in science that are into dance music, I like to think that it’s because if you’re into science, and you’re quite intelligent, but we also like to go and have a good rave.

Jayda:

Yeah, I think everyone needs to, like, let it all out and have a good dance. You know, get those endorphins going. Especially when you’re studying about climate change, yeah, really helps.

Hannah Stitfall:

So Jayda, for our listeners into podcast, you’ve got your own one coming out.

Jayda:

Yes, I’ve been working on my own podcast, it’s called Here’s Hoping. And it really was born out of this entire experience of this film, because the film is so based on hope. And it really got me actually researching about what hope actually means. And I am a big Brené Brown fan. Shout out to Brené Brown, and she wrote this book called Atlas of the Heart. And it really is a dictionary about emotions, and what emotions actually mean, and how they are related to each other.

So she talks about hope. And hope is essentially when you have three things; when you have a goal, and when you have a pathway, and when you have agency for that goal and pathway, when you actually are able to believe in yourself. When you have those three things, you are able to have hope. And that’s basically what this podcast is about.

Hannah Stitfall:

Well enough. I can’t wait to listen to that.

Jayda:

It’s been really amazing doing like, you know, just filming all the beginning episodes for this because it’s supposed to come out at the top of May, hopefully and so, yeah, it’s been really wonderful hearing everyone’s stories of hope.

Hannah Stitfall:

Oh Jayda, thank you so much for coming in today. I can’t wait to see the film. And I know our listeners are going to be on the edge of this as well. Keep up the brilliant work, the dance music and saving the planet. I mean, it’s a win-win.

Jayda:

Trying over here. Thank you so much for having me. I truly appreciate it. Bye!

Hannah Stitfall:

In our next and final episode, we’re looking to the future. And I meet someone who is on the front lines of the oceans Treaty, which was finally passed last year after decades of negotiations. It was a huge deal. And I’m asking: How much is it really going to help. But before that, we’re going to Brazil, where a group of fishermen have developed a very special working relationship with the dolphins there.

Wilson Francisco de Santos (translated):

My name is Wilson Francisco de Santos. I live on Avenida Getúlio Vargas, Magalhaes, Laguna, Santa Catarina. I am currently retired and fish all the time here in portão. It has always been like this for as long as I can remember that people benefit from the dolphin for their and their family’s survival.

These fishing is very important because the dolphin if there were no dolphins here, we would hardly catch any fish because the canal is wide, and most of the fish pass through the middle of the canal. And the dolphin goes to the middle of the canal and brings the fish to the barranco on the edge that we call barranco. He brings it there and he knows that people are there to cast their nets. And by the gesture he makes we know it’s good fish to catch. We catch the fish and he also benefits because every time we cast our nets fish come out and he eats fish from our casts. And it’s a very good interaction because the dolphins know we are there and we know them all. They all have names and he knows that we are there. That’s why he works here in this place. He doesn’t even go to another place that’s good for fishing.

This fishing here with dolphins started more than 100 years ago, because my father fished here. And if he was here today, he would be 120 years old. So it’s much more than 100 years old, and he was already net cast fishing when he was a kid.

For all the riverside people here who live of fishing to feed themselves or use fishing for their survival. To actually leave a fishing it is of great importance, because if there is no dolphins, they won’t catch the amount of fish that died during the day. The fourth and final sentence is that we must always preserve this here, not only the dolphins, but this entire lagoon complex. Because if the lagoon dies, the dolphins also die.

What we have to have is an awareness of preserving this entire lagoon complex. So that this water remains more or less pure. So this will bring benefits for the general population.

This episode was brought to you by Greenpeace and Crowd Network. It’s hosted by me, wildlife filmmaker and broadcaster Hannah Stitfall. It is produced by Anastasia Auffenberg, and our executive producer Steve Jones. The music we use is from our partners BMG Production Music. Archive courtesy of Greenpeace. The team at Crowd Network is Catalina Nogueira, Archie Built Cliff, George Sampson and Robert Wallace. The team at Greenpeace is James Hansen, Flora Hevesi, Alex Yallop, Janae Mayer and Alice Lloyd Hunter. Thanks for listening and see you next week. Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Add your name to call on leaders to create new ocean sanctuaries and protect our blue planet.

Texte intégral (1693 mots)

This story was originally posted by Greenpeace Argentina in Spanish.

Clearing and deforestation are aggressively advancing on the native forests of northern Argentina, according to a recent report from Greenpeace Argentina based on satellite monitoring imagery.

To understand the magnitude of the damage caused, the images below show some of the highlights from this new investigation along with part of the photographic survey of cleared areas.

During 2023, 126,149 hectares of native forests were lost in the north of the country, 6.2% more than in 2022.

It’s clear that there was an increase in land clearings last year, especially illegally.

100% of the clearings in Chaco and 80% of the clearings in Santiago del Estero were illegal.

The main cause of the loss of native forests in Argentina is the growth of the agricultural industry, mainly for intensive livestock farming and genetically modified soybeans, which are mostly exported to Asia and Europe.

The increasing levels of deforestation in Argentina and around the world intensify the consequences of climate change, which range from more and frequent extreme weather events, to the extinction of species, displacement of native and Indigenous communities and impacts on human health.

Meri Castro is a Digital Content Creator at Greenpeace Andino.

Texte intégral (1520 mots)

Oceans are life and all life is connected.

Wherever we live, we need the oceans. And the oceans need all of us, everywhere, to push for their protection. There is no green and just future anywhere without protection for our blue oceans and all who depend on them.

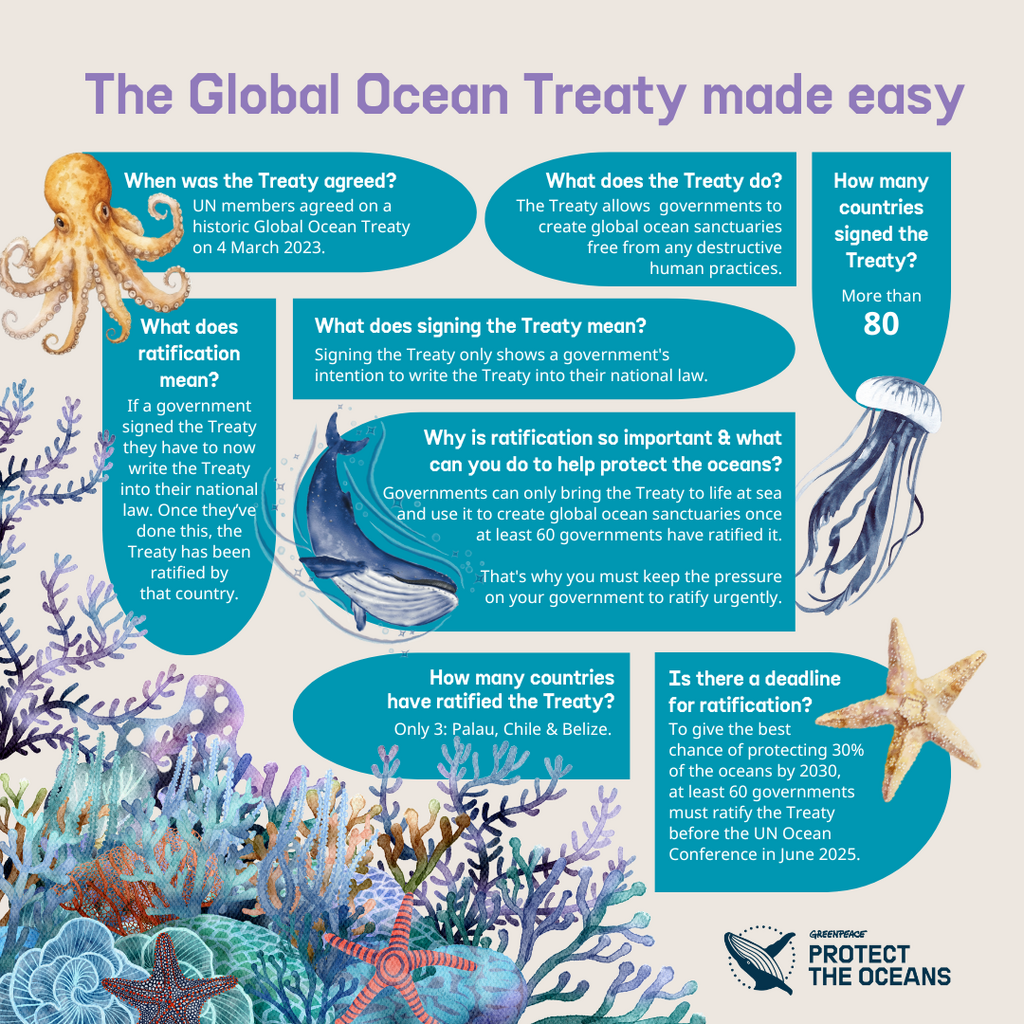

The adoption of the Global Oceans Treaty by the United Nations in June 2023 was a massive step toward ocean protection. It took decades of work from many nations and organisations and the support of millions to achieve, but there is still work to do: The Treaty is a powerful tool — which can be used to create vast ocean sanctuaries where marine life can recover and thrive — but will only enter into force once at least 60 governments have written it into their national law.

The world is watching — and waiting on — this countdown for ocean protection!

Which countries have written the Global Oceans Treaty into law?

From early ratifiers like Palau and Chile and all the way through the number 60 we’ll be tracking nations as they sign the treaty into law.

Countries to ratify: Palau, Chile, Belize, Seychelles, the European Union

Don’t see your home or resident nation included above? Add your name to our global petition to call on leaders to create new ocean sanctuaries and protect our blue planet:

Add your name to call on leaders to create new ocean sanctuaries and protect our blue planet.

Greenpeace urges governments to ratify the Treaty by the UN Ocean Conference in Nice in June 2025, and at the same time to create new marine protected areas.

From Treaty to Sanctuaries

With a heating climate, overfishing and pollution pushing our oceans to the brink of collapse, world leaders need to sign the Treaty into law to bring it into force and unlock its potential for creating ocean sanctuaries that can ensure we protect at least 30% of the oceans by 2030. Alongside ratification, governments must also start to develop the first ocean sanctuaries proposals.

In September 2023, Greenpeace International published 30×30: From Global Ocean Treaty to Protection at Sea setting out the political process to deliver protection for the global oceans.

Alongside ratification, governments must also start to develop the first ocean sanctuaries proposals. The report outlines the political steps and actions necessary to establish ocean sanctuaries using the Treaty and recommends three specific sites on the high seas to be the first set of ocean sanctuaries, due to their ecological significance: the Sargasso Sea, the Emperor Seamounts in the Northwest Pacific Ocean and the South Tasman Sea/Lord Howe Rise between Australia and New Zealand.

We’ve come so far since 2005, when Greenpeace first publicly called for a new treaty under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which would protect biodiversity and provide tools to create marine protected areas on the high seas.

The journey toward safer oceans continues, and we’ll only make it far as we go together!

Becca Field, Chris Greenberg, and Gaby Flores are Multimedia and Content Editors at Greenpeace International.

Reporterre

Bon Pote

Actu-Environnement

Amis de la Terre

Aspas

Biodiversité-sous-nos-pieds

Bloom

Canopée

Décroissance (la)

Deep Green Resistance

Déroute des routes

Faîte et Racines

Fracas

France Nature Environnement AR-A

Greenpeace Fr

JNE

La Relève et la Peste

La Terre

Le Sauvage

Limite

Low-Tech Mag.

Motus & Langue pendue

Mountain Wilderness

Negawatt

Observatoire de l'Anthropocène

Présages

Terrestres

Reclaim Finance

Réseau Action Climat

Résilience Montagne

SOS Forêt France

Stop Croisières