21.02.2026 à 01:00

Capitalisme, IA et éducation

Ploum

Texte intégral (594 mots)

Capitalisme, IA et éducation

Extrait de mon journal du 29 janvier, en lisant "Comprendre le pouvoir" de Chomsky.

Le capitalisme n’a pas créé le système éducatif par humanisme, mais parce qu’il avait besoin d’employés qualifiés pour produire de la croissance. L’automatisation ayant détruit la culture de l’artisan et de l’ouvrier, raison du combat des luddites, une large population se trouvait réduite à se mettre au service des machines.

Mais les progrès de l’automatisation rendaient ce besoin de servants peu qualifiés de moins en moins nécessaire tout en nécessitant des personnes comprenant les machines afin de les entretenir et de les améliorer. Un système éducatif s’est donc naturellement mis en place dans les sociétés capitalistes, créant une élite intellectuelle dévouée au capitalisme.

Mais cette suréducation a créé trop de citoyens critiques qui remettent en cause les principes mêmes de la croissance infinie, notamment à cause des limites écologiques.

Face à cette suréducation, les guerres, les menaces de tout ordre et le totalitarisme politique permettent de restreindre l’éducation ou, a minima, de détourner l’attention. L’éducation informatique est la principale cible, car l’informatique est devenue la colonne vertébrale de la société capitaliste. Ne pas comprendre les enjeux informatiques rend même les citoyens les plus engagés totalement impuissants.

La promesse de l’IA, c’est justement de diminuer le besoin d’éducation tout en gardant un degré de production équivalent. Tout employé peut redevenir une main-d’œuvre peu qualifiée et interchangeable. L’IA est un Fordisme intellectuel.

Car les monopoles, la surveillance permanente, la consommation, l’érosion des droits et l’IAfication du travail ne sont que des outils pour garder les citoyens sous contrôle et dans les rails du capitalisme de production.

Et si ces citoyens s’imaginent échapper à ce contrôle grâce à leur groupe Facebook "anticapitaliste" ou un groupe Whatsapp "centrale d’achat solidaire du quartier", c’est encore mieux ! C’est plus subtil ! De toute façon, ils bossent la journée pour Microsoft et se contentent d’une image du monde générée par Google ou Meta.

Leur vie professionnelle est asservie par Microsoft, leur vie privée par Meta/Facebook et leurs centres d’intérêt sont contrôlés par Google. Maintenant que les humains sont définitivement ferrés, il est temps de réduire progressivement leur degré d’éducation et de connaissance afin d’améliorer leur servilité.

À propos de l’auteur :

Je suis Ploum et je viens de publier Bikepunk, une fable écolo-cycliste entièrement tapée sur une machine à écrire mécanique. Pour me soutenir, achetez mes livres (si possible chez votre libraire) !

Recevez directement par mail mes écrits en français et en anglais. Votre adresse ne sera jamais partagée. Vous pouvez également utiliser mon flux RSS francophone ou le flux RSS complet.

16.02.2026 à 01:00

Préface à « La déception informatique »

Ploum

Texte intégral (1477 mots)

Préface à « La déception informatique »

Ce texte est la préface que j’ai écrite pour le livre « La déception informatique » d’Alain Lefebvre ». Le livre n’est malheureusement disponible en version papier que sur… gasp… Amazon ! Mais les versions epub et pdf sont librement téléchargeables !

- La déception informatique ! (www.alain-lefebvre.com)

- La déception informatique-V1.0.epub (drive.google.com)

- La déception informatique-V1.0.pdf (drive.google.com)

- La déception informatique, format Kindle (www.amazon.fr)

- La déception informatique, version papier (www.amazon.fr)

Depuis quelques années, lorsque je dois acheter un équipement électroménager ou même une voiture, j’insiste auprès du vendeur pour avoir une solution qui fonctionne sans connexion permanente et ne nécessite pas d’app sur smartphone.

La réaction est toujours la même : « Ah ? Vous avez du mal avec la technologie ? »

Oui, j’ai du mal. Et pourtant j’ai publié mon premier livre sur l’informatique en 2005. Et pourtant, j’enseigne depuis 10 ans dans le département informatique de l’École Polytechnique de Louvain.

Alain et moi sommes des professionnels de l’informatique qui avons, chacun dans notre genre, bâti une carrière dans l’informatique et la technologie. Nous pouvons même nous enorgueillir d’une certaine reconnaissance parmi les spécialistes du domaine. Nous baignons dedans depuis des décennies. Bref, Alain et moi sommes des "geeks", de celles et ceux qui perçoivent un ordinateur comme une extension d’eux-mêmes.

Alors, je me contente le plus souvent de répondre au vendeur : « Quand on sait comment est fabriqué le fast-food, on arrête d’en manger… » La discussion s’arrête là.

Mais au fond, le vendeur a raison : Alain et moi avons du mal avec la technologie moderne. Pas parce que nous ne la comprenons pas. Au contraire, parce que nous la comprenons trop bien. Nous savons ce qu’elle a été, ce qu’elle aurait pu être. Et nous pleurons sur ce qu’elle est aujourd’hui.

En toute transparence, je me suis souvent demandé si ma réaction n’était pas une simple conséquence de l’âge. Un très traditionnel syndrome du « C’était mieux avant » par lequel semble passer chaque génération. Il y a certainement un peu de ça.

Mais pas que…

Alain pourrait être mon père. Il est de 21 ans mon aîné et a construit l’essentiel de sa carrière alors que je tentais de faire fonctionner des lignes de BASIC sur mon premier 386. Alors que je concevais mes premiers sites web, Alain introduisait sa société en bourse en pleine implosion de la bulle Internet.

Nous sommes de générations différentes, nous avons un vécu informatique sans aucun rapport. Et pourtant, nous arrivons à des réflexions similaires.

Réflexions qui semblent partagées par des lecteurs de mon blog de toutes cultures et de tout âge (certains étant adolescents). Réflexions auxquelles se joignent aussi parfois certains de mes étudiants.

Nous avions cru que l’ubiquité des ordinateurs nous permettrait de faire ce que nous voulions, de programmer ceux-ci pour obéir aux moindres de nos désirs.

Mais, dans nos poches, se trouvent désormais des ordinateurs qu’il est interdit ou très compliqué de modifier. La programmation est désormais balisée et réservée à ce que trois ou quatre multinationales américaines veulent bien nous laisser faire.

Nous pensions que l’informatisation de la société nous libérerait de la paperasserie administrative qui deviendrait rationnelle et automatisable.

Au lieu de ça, nous sommes en permanence en train de lutter pour remplir des formulaires qui n’acceptent pas nos réponses, nous devons régulièrement faire la mise à jour de tous nos appareils électroniques et nous devons nous battre contre des procédures informatiques dont nous savons, de par notre expérience, qu’elles ont été explicitement construites pour nous décourager.

Nous croyions que la possibilité pour tout un chacun de s’exprimer et d’échanger sur un réseau mondial allait ouvrir une nouvelle ère de coopération et de partage de connaissances et de culture.

À la place, nous avons créé l’infrastructure parfaite où les beuglements de fascistes sont entourés des publicités les plus éhontées.

Techniquement, nous étions conscients que se servir d’un ordinateur nécessitait un apprentissage. Nous étions certains que cet apprentissage serait de moins en moins difficile.

Mais, bien que les couleurs soient devenues plus vivantes, les photos plus précises, les interfaces se sont complexifiées à outrance, forçant l’immensité des utilisateurs à rester dans les deux ou trois fonctions connues et balisées. Ce qui était à la portée d’un amateur il y a 20 ans nécessite aujourd’hui une armée de professionnels.

Au nom d’intérêts financiers, le partage de culture a très vite été criminalisé alors que les injures et les discours de haine, eux, étaient amplifiés pour servir de support aux messages publicitaires omniprésents.

Nous avions cet espoir que la démocratisation de l’informatique transformerait graduellement chaque personne en citoyen intéressé, curieux, éveillé.

Au lieu de cela, nous observons des masses faire la file pour dépenser un mois de salaire afin d’acquérir un petit écran brillant conçu explicitement pour être addictif et abrutir, n’encourageant qu’à une chose : consommer toujours plus.

« Avec l’informatique, tout le monde aura accès au savoir et à l’éducation » criions-nous !

Aujourd’hui, la plupart des écoles ont un cursus informatique qui se réduit à surtout arrêter de penser et, à la place, produire des transparents dans Microsoft PowerPoint.

Quand on a eu de tels rêves, lorsqu’on sait que ces rêves sont à la fois technologiquement possible mais, surtout, que nous les avons touchés du doigt, il y a de quoi être déçu.

Ce n’est pas que l’informatique n’ait pas exaucé nos rêves ! Non, c’est pire : elle a produit exactement le contraire. Elle semble avoir amplifié les problèmes que nous souhaitions résoudre tout en créant des nouveaux, comme l’espionnage permanent auquel nous sommes désormais soumis. Les atrocités technologiques que j’exagérais dans « Printeurs », mon roman cyberpunk dystopique, semblent aujourd’hui banales voire en deça de la réalité.

Déçus, nous le sommes, Alain et moi. Et le titre de son livre le résume admirablement : la déception informatique.

Un livre qui est peut‑être aussi une forme de mea culpa. Nous avons contribué à faire naître ce monstre de Frankenstein qu’est l’informatique moderne. Il est plus que temps de tirer la sonnette d’alarme, de réveiller celles et ceux d’entre nous qui se voilent encore la face…

14 février 2026

À propos de l’auteur :

Je suis Ploum et je viens de publier Bikepunk, une fable écolo-cycliste entièrement tapée sur une machine à écrire mécanique. Pour me soutenir, achetez mes livres (si possible chez votre libraire) !

Recevez directement par mail mes écrits en français et en anglais. Votre adresse ne sera jamais partagée. Vous pouvez également utiliser mon flux RSS francophone ou le flux RSS complet.

11.02.2026 à 01:00

Do not apologize for replying late to my email

Ploum

Texte intégral (1538 mots)

Do not apologize for replying late to my email

You don’t need to apologize for taking hours, days, or years to reply to one of my emails.

If we are not close collaborators, and if I didn’t explicitly tell you I was waiting for your answer within a specific timeframe, then please stop apologizing for replying late!

This is a trend I’m witnessing, probably caused by the addiction to instant messaging. Most of the emails I receive these days contain some sort of apology. I received an apology from someone who took five hours to reply to what was a cold and unimportant email. I received apologies in what was a reply to a reply I had sent only a couple of days earlier.

Apologizing for taking time to reply to my email is awkward and makes me uncomfortable.

It also puts a lot of pressure on me: what if I take more time than you to reply? Isn’t the whole point of asynchronous communication to be… asynchronous? Each on its own rhythm?

I was not waiting for your email in the first place.

As soon as my email was sent, I probably forgot about it. I may have thought a lot before writing it. I may have drafted it multiple times. Or not. But as soon as it was in my outbox, it was also out of my mind.

That’s the very point of asynchronous communication. That’s why I use email. I’m not making any assumptions about your availability.

Most of the emails I send are replies to emails I received. So, no, I was not waiting for a reply to my reply.

My email might also be an idea I wanted to share with you, a suggestion, a random thought, a way to connect. In all cases, I’m not sitting there, waiting impatiently for your answer.

Even if my email was about requesting some help or collaborating with you, I’ve been trying to move forward anyway. Your reply, whenever it comes, will only be a bonus. But, except if we are in close collaboration and I explicitly said so in the email, I’m not waiting for you!

I don’t want to know all the details of your life.

Yes, you took several days to reply to my email. That’s OK. I don’t need to know that it’s because your mother was dying of cancer or that you were expelled from your house. I’m not making those up! I really receive that kind of apology from people who took several days to reply to emails that look trivial in comparison.

Life happens. If you have things more important to do than replying to my email, then, for god’s sake, don’t reply to it. I get it! I’m human too. If I sometimes reply to all the emails I receive for several days, I may also archive them quickly for weeks because I don’t have the mental space.

If you want to reply but don’t have time, put the burden on me

If I’m asking you something and you really would like to take the time to reply to my email, it is OK to simply send one line like

Hey Ploum, I don’t have the time and mental space right now. Could you contact me again in 6 months to discuss this idea?

Then archive or delete my email. That’s fine. If I really want your input, I will manage to remind you in 6 months. You don’t need to justify. You don’t need to explain. Being short saves time for both of us.

You don’t need to reply at all!

Except if explicitly stated, don’t feel any pressure to reply to one of my emails. Feel free to read and discard the email. Feel free to think about it. Feel free to reply to it, even years later, if it makes sense for you. But, most importantly, feel free not to care!

We all receive too many messages in a day. We all have to make choices. We cannot follow all the paths that look interesting because we are all constrained by having, at most, a couple billion seconds left to live.

Consider whether replying adds any value to the discussion. Is a trivial answer really needed? Is there really something to add? Can’t we both save time by you not replying?

If my email is already a reply to yours, is there something you really want to add? At some point, it is better to stop the conversation. And, as I said, it is not rude: I’m not waiting for your reply!

Don’t tell me you will reply later!

Some people specialize in answering email by explaining why they have no time and that they will reply later.

If I’m not explicitly waiting for you, then that’s the very definition of a useless email. That also adds a lot of cognitive load on you: you promised to answer! The fact that you wrote it makes your brain believe that replying to my email is a daunting task. How will you settle for a quick reply after that? What am I supposed to do with such a non-reply email?

In case an acknowledgement is needed, a simple reply with "thanks" or "received" is enough to inform me that you’ve got the message. Or "ack" if you are a geek.

If you do reply, remind me of the context

If you choose to reply, consider that I have switched to completely different tasks and may have forgotten the context of my own message. When online, my attention span is measured in seconds, so it doesn’t matter if you take 30 minutes or 30 days to answer my email: I guarantee you that I forgot about it.

Consequently, please keep the original text of the whole discussion!

Use bottom-posting style to reply to each question or remark in the body of the original mail itself. Don’t hesitate to cut out parts of the original email that are not needed anymore. Feel free to ignore large parts of the email. It is fine to give a one-line answer to a very long question.

I’m trying to make my emails structured. If there are questions I want you to answer, each question will be on its own line and will end with a question mark. If you do not see such lines, then there’s probably no question to answer.

If you do top posting, please remind me briefly of the context we are in.

Dear Ploum,

I contacted you 6 months ago about my "fooing the bar" project after we met at FOSDEM. You replied to my email with a suggestion of "baring the foo." You also asked a lot of questions. I will answer those below in your own email:

In short, that’s basic mailing-list etiquette.

No, seriously, I don’t expect you to reply!

If there’s one thing to remember, it’s that I don’t expect you to reply. I’m not waiting for it. I have a life, a family, and plenty of projects. The chance I’m thinking about the email I sent you is close to zero. No, it is literally zero.

So don’t feel pressured to reply. Should you really reply in the first place? In case of doubt, drop the email. Life will continue.

If you do reply, I will be honored, whatever time it took for you to send it.

In any case, whatever you choose, do not apologize for replying late!

About the author

I’m Ploum, a writer and an engineer. I like to explore how technology impacts society. You can subscribe by email or by rss. I value privacy and never share your adress.

I write science-fiction novels in French. For Bikepunk, my new post-apocalyptic-cyclist book, my publisher is looking for contacts in other countries to distribute it in languages other than French. If you can help, contact me!

09.02.2026 à 01:00

Offpunk 3.0 "A Community is Born" Release

Ploum

Texte intégral (1450 mots)

Offpunk 3.0 "A Community is Born" Release

For the last four years, I’ve been developing Offpunk, a command-line Web, Gemini, and Gopher browser that allows you to work offline. And I’ve just released version 3.0. It is probably not for everyone, but I use it every single day. I like it, and it seems I’m not alone!

Something wonderful happened on the road leading to 3.0: Offpunk became a true cooperative effort. Offpunk 3.0 is probably the first release that contains code I didn’t review line-by-line. Unmerdify (by Vincent Jousse), all the translation infrastructure (by the always-present JMCS), and the community packaging effort are areas for which I barely touched the code.

So, before anything else, I want to thank all the people involved for sharing their energy and motivation. I’m very grateful for every contribution the project received. I’m also really happy to see "old names" replying from time to time on the mailing list. It makes me feel like there’s an emerging Offpunk community where everybody can contribute at their own pace.

There were a lot of changes between 2.8 and 3.0, which probably means some new bugs and some regressions. We count on you, yes, you!, to report them and make 3.1 a lot more stable. It’s as easy at typing "bugreport" in offpunk!

From the deepest of my terminal, thank you!

But enough with the cheering, let’s jump to…

The 11 most important changes in Offpunk 3.0

0. Use Offpunk in your language.

Offpunk is now translatable and has been translated into Spanish, Galician, and Dutch. Step-in to translate Offpunk into your language! (awesome work by JMCS with the help of Bert Livens)

1. Openk as a standalone tool

"opnk" standalone tool has been renamed to "openk" to make it more obvious. Openk is a command-line tool that tries to open any file in the terminal and, if not possible, opens it in your preferred software, falling back to xdg-open as a last resort.

People using opnk directly should change it everywhere. Users not using "opnk" in their terminal are not affected.

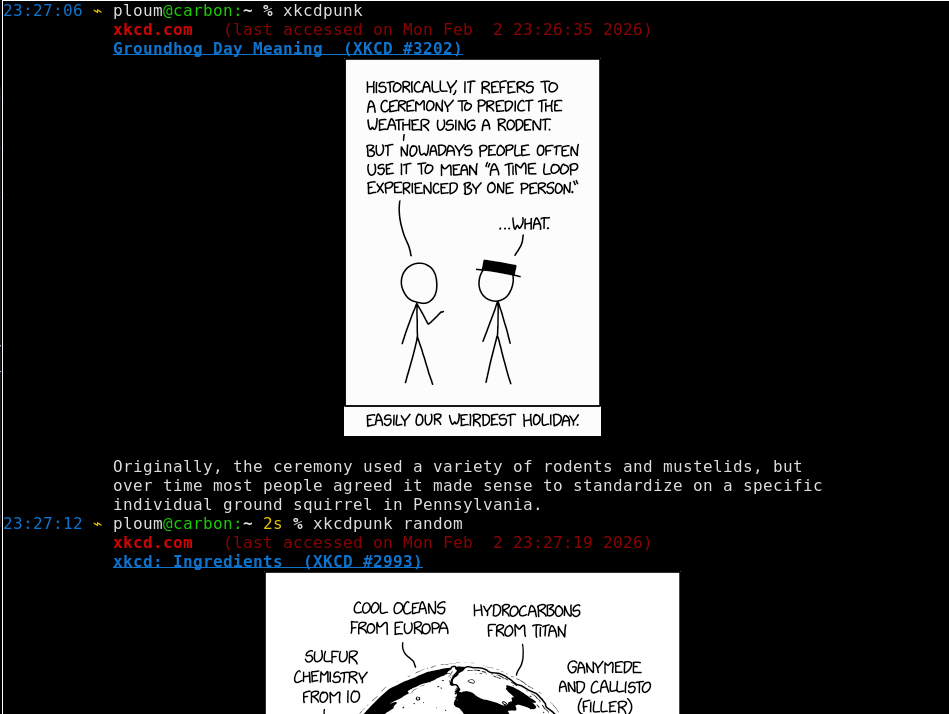

2. See XKCD comics in your terminal

"xkcdpunk" is a new standalone tool that allows displaying XKCD comics directly in your terminal.

3. Get only the good part and remove cruft for thousands of websites

Offpunk now integrates "unmerdify," a library written by Vincent Jousse that extracts the content of HTML articles using the "ftr-site-config" set of rules maintained by the FiveFilters community.

You can contribute by creating or improving rules for your frequently visited websites.

- Site Patterns | FiveFilters.org Docs (help.fivefilters.org)

- fivefilters/ftr-site-config: Site-specific article extraction rules to aid content extractors, feed readers, and 'read later' applications. (github.com)

If no ftr rule is found, Offpunk falls back to "readability," as has been the case since 0.1. "info" will tell you if unmerdify or readability was used to display the content of a page.

To use umerdify, users should manually clone the ftr-site-config repository:

git clone https://github.com/fivefilters/ftr-site-config.git

Then, in their offpunkrc:

set ftr_site_config /path/to/ftr-site-config

Automating this step is an objective for 3.1

4. Offpunk goes social with "share" and "reply"

New social functions: "share" to send the URL of a page by email and "reply" to reply to the author if an email is found. "Reply" will remember the email used for each site/capsule/hole.

5. Browse websites while logged in

Offpunk doesn’t support login into websites. But the new "cookies" command allows you to import a cookie txt file to be used with a given http domain.

From your traditional browser (Firefox, Librewolf, Chromium, … ), log into the website. Then export the cookie with the "cookie-txt" extension. Once you have this "mycookie.txt" text file, launch Offpunk and run:

cookies import mycookie.txt https://domain-of-the-cookie.net/

This allows you, for example, to read LWN.NET if you have a subscription. (contributed by Urja)

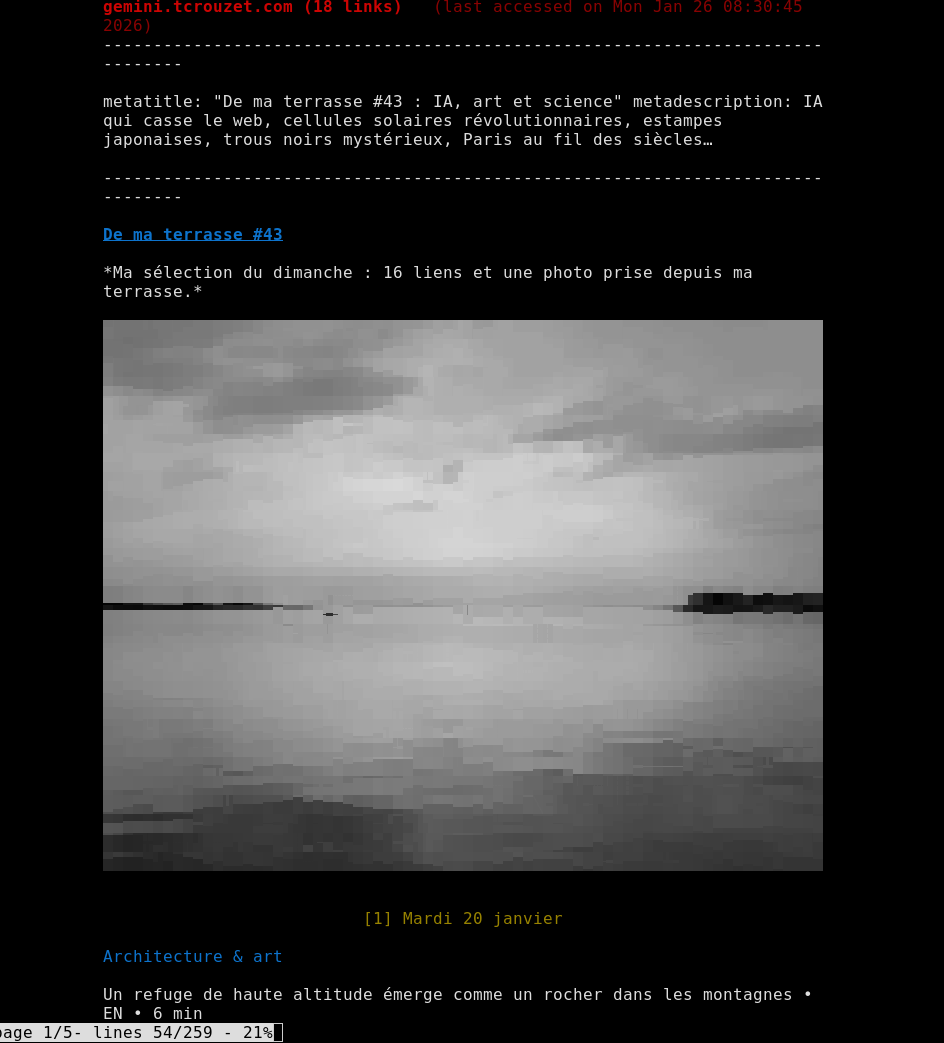

6. Bigger, better images, even in Gemini

Images are now displayed by default in gemini and their display size has been increased.

This can be reverted with the following lines in offpunkrc:

set images_size 40 set gemini_images false

Remember that images are displayed as "blocks" when reading a page but if you access the image URL directly (by following the yellow link beneath), the image will be displayed perfectly if you are using a sixels-compatible terminal.

7. Display hidden RSS/Atom links

If available, links to hidden RSS/Atom feeds are now displayed at the bottom of HTML pages.

This makes the "feed" command a lot less useful and allows you to quickly discover interesting new feeds.

8. Display blocked links

Links to blocked domains are now displayed in red by default.

This can be reverted with the following lines in offpunkrc:

theme blocked_link none

9. Preset themes

Support for multiple themes with "theme preset." Existing themes are "offpunk1" (default), "cyan," "yellow" and "bw." Don’t hesitate to contribute yours!

10. Better redirects and true blocks

"redirects" now operate on the netcache level. This means that no requests to blocked URLs should ever be made (which was still happening before)

And many changes, improvements and bugfixes

- "root" is now smarter and goes to the root of a website, not the domain.

Old behaviour can still be achieved with "root /"

- "ls" command is deprecated and has been replaced by "links"

- new "websearch" command configured to use wiby.me by default

- "set default_cmd" allows you to configure what Offpunk will do when pressing enter on an empty command line. By default, it is "links 10."

- "view switch" allows you to switch between normal and full view (contributed by Andrew Fowlie)

- "help help" will allow you to send an email to the offpunk-users mailing list

- "bugreport" will send a bug report to the offpunk-devel mailing list

- And, of course, multiple bugfixes…

About the author

I’m Ploum, a writer and an engineer. I like to explore how technology impacts society. You can subscribe by email or by rss. I value privacy and never share your adress.

I write science-fiction novels in French. For Bikepunk, my new post-apocalyptic-cyclist book, my publisher is looking for contacts in other countries to distribute it in languages other than French. If you can help, contact me!

31.01.2026 à 01:00

The Disconnected Git Workflow

Ploum

Texte intégral (1425 mots)

The Disconnected Git Workflow

Using git-send-email while being offline and with multiple email accounts

WARNING: the following is a technical reminder for my future self. If you don’t use the "git" software, you can safely ignore this post.

The more I work with git-send-email, the less I find the GitHub interface sufferable.

Want to send a small patch to a GitHub project? You need to clone the repository, push your changes to your own branch, then ask for a pull request using the cumbersome web interface, replying to comments online while trying to avoid smileys.

With git send-email, I simply work offline, do my local commit, then:

git send-email HEAD^

And I’m done. I reply to comments by email, with Vim/Mutt. When the patch is accepted, getting a clean tree usually boils down to:

git pull

git rebase

Yeah for git-send-email!

And, yes, I do that while offline and with multiple email accounts. That’s one more reason to hate GitHub.

- How GitHub monopoly is destroying the open source ecosystem (ploum.net)

- We need to talk about your GitHub addiction (ploum.net)

One mail account for each git repository

The secret is not to configure email accounts in git but to use "msmtp" to send email. Msmtp is a really cool sendmail replacement.

In .msmtprc, you can configure multiple accounts with multiple options, including calling a command to get your password.

# account 1 - pro account work host smtp.company.com port 465 user login@company.com from ploum@company.com password SuPeRstr0ngP4ssw0rd tls_starttls off # personal account for FLOSS account floss host mail.provider.net port 465 user ploum@mydomain.net from ploum@mydomain.net from ploum*@mydomain.net passwordeval "cat ~/incredibly_encrypted_password.txt | rot13" tls_starttls off

The important bit here is that you can set multiple "from" addresses for a given account, including a regexp to catch multiple aliases!

Now, we will ask git to automatically use the right msmtp account. In your global .gitconfig, set the following:

[sendemail] sendmailCmd = /usr/bin/msmtp --set-from-header=on envelopeSender = auto

The "envelopesender" option will ensure that the sendemail.from will be used and given to msmtp as a "from address." This might be redundant with "--set-from-header=on" in msmtp but, in my tests, having both was required. And, cherry on the cake, it automatically works for all accounts configured in msmtprc.

Older git versions (< 2.33) don’t have sendmailCmd and should do:

[sendemail] smtpserver = /usr/bin/msmtp smtpserveroption = --set-from-header=on envelopesender = auto

I usually stick to a "ploum-PROJECT@mydomain.net" for each project I contribute to. This allows me to easily cut spam when needed. So far, the worst has been with a bug reported on the FreeBSD Bugzilla. The address used there (and nowhere else) has since been spammed to death.

In each git project, you need to do the following:

1. Set the email address used in your commit that will appear in "git log" (if different from the global one)

git config user.email "Ploum <ploum-PROJECT@mydomain.net>"

2. Set the email address that will be used to actually send the patch (could be different from the first one)

git config sendemail.from "Ploum <ploum-PROJECT@mydomain.net>"

3. Set the email address of the developer or the mailing list to which you want to contribute

git config sendemail.to project-devel@mailing-list.com

Damn, I did a commit with the wrong user.email!

Yep, I always forget to change it when working on a new project or from a fresh git clone. Not a problem. Just use "git config" like above, then:

git commit --amend --reset-author

And that’s it.

Working offline

I told you I mostly work offline. And, as you might expect, msmtp requires a working Internet connection to send an email.

But msmtp comes with three wonderful little scripts: msmtp-enqueue.sh, msmtp-listqueue.sh and msmtp-runqueue.sh.

The first one saves your email to be sent in ~/.msmtpqueue, with the sending options in a separate file. The second one lists the unsent emails, and the third one actually sends all the emails in the queue.

All you need to do is change the msmtp line in your global .gitconfig to call the msmtpqueue.sh script:

[sendemail]

sendmailcmd = /usr/libexec/msmtp/msmtpqueue/msmtp-enqueue.sh --set-from-header=on

envelopeSender = auto

In Debian, the scripts are available with the msmtp package. But the three are simple bash scripts that can be run from any path if your msmtp package doesn’t provide them.

You can test sending a mail, then check the ~/.msmtpqueue folder for the email itself (.email file) and the related msmtp command line (.msmtp file). It happens nearly every day that I visit this folder to quickly add missing information to an email or simply remove it completely from the queue.

Of course, once connected, you need to remember to run:

/usr/libexec/msmtp/msmtpqueue/msmtp-runqueue.sh

If not connected, mails will not be sent and will be kept in the queue. This line is obviously part of my do_the_internet.sh script, along with "offpunk --sync".

It is not only git!

If it works for git, it works for any mail client. I use neomutt with the following configuration to use msmtp-enqueue and reply to email using the address it was sent to.

set sendmail="/usr/libexec/msmtp/msmtpqueue/msmtp-enqueue.sh --set-from-header=on" unset envelope_from_address set use_envelope_from set reverse_name set from="ploum@mydomain.net" alternates ploum[A-Za-z0-9]*@mydomain.net

Of course, the whole config is a little more complex to handle multiple accounts that are all stored locally in Maildir format through offlineimap and indexed with notmuch. But this is a bit out of the scope of this post.

At least, you get the idea, and you could probably adapt it to your own mail client.

Conclusion

Sure, it’s a whole blog post just to get the config right. But there’s nothing really out of this world. And once the setup is done, it is done for good. No need to adapt to every change in a clumsy web interface, no need to use your mouse. Simple command lines and simple git flow!

Sometimes, I work late at night. When finished, I close the lid of my laptop and call it a day without reconnecting my laptop. This allows me not to see anything new before going to bed. When this happens, queued mails are sent the next morning, when I run the first do_the_internet.sh of the day.

And it always brings a smile to my face to see those bits being sent while I’ve completely forgotten about them…

About the author

I’m Ploum, a writer and an engineer. I like to explore how technology impacts society. You can subscribe by email or by rss. I value privacy and never share your adress.

I write science-fiction novels in French. For Bikepunk, my new post-apocalyptic-cyclist book, my publisher is looking for contacts in other countries to distribute it in languages other than French. If you can help, contact me!

22.01.2026 à 01:00

Why there’s no European Google?

Ploum

Texte intégral (1491 mots)

Why there’s no European Google?

And why it is a good thing!

With some adjustments, this post is mostly a translation of a post I published in French three years ago. In light of the European Commission’s "call for evidence on Open Source," and as a professor of "Open Source Strategies" at École Polytechnique de Louvain, I thought it was a good idea to translate it into English as a public answer to that call.

- Pourquoi n’y a-t-il pas de Google européen ? (ploum.net)

- European Commission issues call for evidence on open source (lwn.net)

Google (sorry, Alphabet), Facebook (sorry, Meta), Twitter (sorry, X), Netflix, Amazon, Microsoft. All those giants are part of our daily personal and professional lives. We may even not interact with anything else but them. All are 100% American companies.

China is not totally forgotten, with Alibaba, TikTok, and some services less popular in Europe yet used by billions worldwide.

What about European tech champions? Nearly nothing, to the great sadness of politicians who believe that the success of a society is measured by the number of billionaires it creates.

Despite having few tech-billionaires, Europe is far from ridiculous. In fact, it’s the opposite: Europe is the central place that allowed most of our tech to flourish.

The Internet, the interconnection of most of the computers in the world, has existed since the late sixties. But no protocol existed to actually exploit that network, to explore and search for information. At the time, you needed to know exactly what you wanted and where to find it. That’s why the USA tried to develop a protocol called "Gopher."

At the same time, the "World Wide Web," composed of the HTTP protocol and the HTML format, was invented by a British citizen and a Belgian citizen who were working in a European research facility located in Switzerland. But the building was on the border with France, and there’s much historical evidence pointing to the Web and its first server having been invented in France.

It’s hard to be more European than the Web! It looks like the Official European Joke! (And, yes, I consider Brits Europeans. They will join us back, we miss them, I promise.)

Gopher is still used by a few hobbyists (like yours trully), but it never truly became popular, except for a very short time in some parts of America. One of the reasons might have been that Gopher’s creators wanted to keep their rights to it and license any related software, unlike the European Web, which conquered the world because it was offered as a common good instead of seeking short-term profits.

While Robert Cailliau and Tim Berners-Lee were busy inventing the World Wide Web in their CERN office, a Swedish-speaking Finnish student started to code an operating system and make it available to everyone under the name "Linux." Today, Linux is probably the most popular operating system in the world. It runs on any Android smartphone, is used in most data centers, in most of your appliances, in satellites, in watches and is the operating system of choice for many of the programmers who write the code you use to run your business. Its creator, the European Linus Torvalds, is not a billionaire. And he’s very happy about it: he never wanted to become one. He continued coding and wrote the "git" software, which is probably used by 100% of the software developers around the world. Like Linux, Git is part of the common good: you can use it freely, you can modify it, you can redistribute it, you can sell it. The only thing you cannot do? Privatize it. This is called "copyleft."

In 2017, a decentralized and ethical alternative to Twitter appeared: Mastodon. Its creator? A German student, born in Russia, who had the goal of allowing social network users to leave monopolies to have humane conversations without being spied on and bombarded with advertising or pushed-by-algorithm fake news. Like Linux, like git, Mastodon is copyleft and now part of the common goods.

Allowing human-scale discussion with privacy and without advertising was also the main motivation behind the Gemini protocol (whose name has since been hijacked by Google AI). Gemini is a stripped-down version of the Web which, by design, is considered definitive. Everybody can write Gemini-related software without having to update it in the future. The goal is not to attract billions of users but to be there for those who need it, even in the distant future. The creator of the Gemini protocol wishes to remain anonymous, but we know that the project started while he was living in Finland.

I could continue with the famous VLC media player, probably the most popular media player in the world. Its creator, the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Kempf, refused many offers that would have made him a very rich man. But he wanted to keep VLC a copyleft tool part of the common goods.

Don’t forget LibreOffice, the copyleft office suite maintained by hundreds of contributors around the world under the umbrella of the Document Foundation, a German institution.

We often hear that Europeans don’t have, like Americans, the "success culture." Those examples, and there are many more, prove the opposite. Europeans like success. But they often don’t consider "winning against the whole society" as one. Instead, they tend to consider success a collective endeavour. Success is when your work is recognized long after you are gone, when it benefits every citizen. Europeans dream big: they hope that their work will benefit humankind as a whole!

We don’t want a European Google Maps! We want our institutions at all levels to contribute to OpenStreetMap (which was created by a British citizen, by the way).

Google, Microsoft, Facebook may disappear tomorrow. It is even very probable that they will not exist in fourty or fifty years. It would even be a good thing. But could you imagine the world without the Web? Without HTML? Without Linux?

Those European endeavours are now a fundamental infrastructure of all humanity. Those technologies are definitely part of our long-term history.

In the media, success is often reduced to the size of a company or the bank account of its founder. Can we just stop equating success with short-term economic growth? What if we used usefulness and longevity? What if we gave more value to the fundamental technological infrastructure instead of the shiny new marketing gimmick used to empty naive wallets? Well, I guess that if we changed how we measure success, Europe would be incredibly successful.

And, as Europeans, we could even be proud of it. Proud of our inventions. Proud of how we contribute to the common good instead of considering ourselves American vassals.

Some are proud because they made a lot of money while cutting down a forest. Others are proud because they are planting trees that will produce the oxygen breathed by their grandchildren. What if success was not privatizing resources but instead contributing to the commons, to make it each day better, richer, stronger?

The choice is ours. We simply need to choose whom we admire. Whom we want to recognize as successful. Whom we aspire to be when we grow up. We need to sing the praises of our true heroes: those who contribute to our commons.

About the author

I’m Ploum, a writer and an engineer. I like to explore how technology impacts society. You can subscribe by email or by rss. I value privacy and never share your adress.

I write science-fiction novels in French. For Bikepunk, my new post-apocalyptic-cyclist book, my publisher is looking for contacts in other countries to distribute it in languages other than French. If you can help, contact me!

- Persos A à L

- Carmine

- Mona CHOLLET

- Anna COLIN-LEBEDEV

- Julien DEVAUREIX

- Cory DOCTOROW

- Lionel DRICOT (PLOUM)

- EDUC.POP.FR

- Marc ENDEWELD

- Michel GOYA

- Hubert GUILLAUD

- Gérard FILOCHE

- Alain GRANDJEAN

- Hacking-Social

- Samuel HAYAT

- Dana HILLIOT

- François HOUSTE

- Tagrawla INEQQIQI

- Infiltrés (les)

- Clément JEANNEAU

- Paul JORION

- Michel LEPESANT

- Persos M à Z

- Henri MALER

- Christophe MASUTTI

- Jean-Luc MÉLENCHON

- MONDE DIPLO (Blogs persos)

- Richard MONVOISIN

- Corinne MOREL-DARLEUX

- Timothée PARRIQUE

- Thomas PIKETTY

- VisionsCarto

- Yannis YOULOUNTAS

- Michaël ZEMMOUR

- LePartisan.info

- Numérique

- Blog Binaire

- Christophe DESCHAMPS

- Louis DERRAC

- Olivier ERTZSCHEID

- Olivier EZRATY

- Framablog

- Romain LECLAIRE

- Tristan NITOT

- Francis PISANI

- Irénée RÉGNAULD

- Nicolas VIVANT

- Collectifs

- Arguments

- Blogs Mediapart

- Bondy Blog

- Dérivation

- Économistes Atterrés

- Dissidences

- Mr Mondialisation

- Palim Psao

- Paris-Luttes.info

- ROJAVA Info

- Créatifs / Art / Fiction

- Nicole ESTEROLLE

- Julien HERVIEUX

- Alessandro PIGNOCCHI

- Laura VAZQUEZ

- XKCD